Editorial or native advertising: The key to success is to be reader-centric

So what is native advertising really?

Definitions of what it is and what it isn’t spread far and wide across the web as associations, vendors, publishers, marketers and the media attempt to wrap their heads around this shiny new revenue stream.

The International Advertising Bureau (IAB) defines native ads as “paid advertisements that are so cohesive with the page content, assimilated into the design, and consistent with the platform behaviour that the viewer simply feels that they belong.”

Sharethrough (a member of the IAB Native Advertising Task Force), calls “a form of paid media where the ad experience follows the natural form and function of the user experience in which it is placed”.

Why a promotional practice that has been around for over a century needs a new definition, I don’t get. There’s really nothing new about native advertising, other than its name coined in 2011. Native ads have been served across all forms of medium for decades; we just called them advertorials.

Check out this 1914 Cadillac-sponsored “native ad” in The Saturday Evening Post.

Except for the layout and use of graphics, there’s not much difference between the past and the present when it comes to sponsored content.

So what’s all the fuss about? Why is there so much hype about something we’ve had in our advertising arsenal since long before the dawn of digital?

Few would argue that banner blindness is an electronic epidemic for which there is no cure.

But are native ads digital media’s last hope to recapture the eyeballs, trust and loyalty of consumers they’ve been abusing for years with poor quality, invasive and overly commoditised banner, interstitial and instream promotions? Maybe…

Hope springs eternal

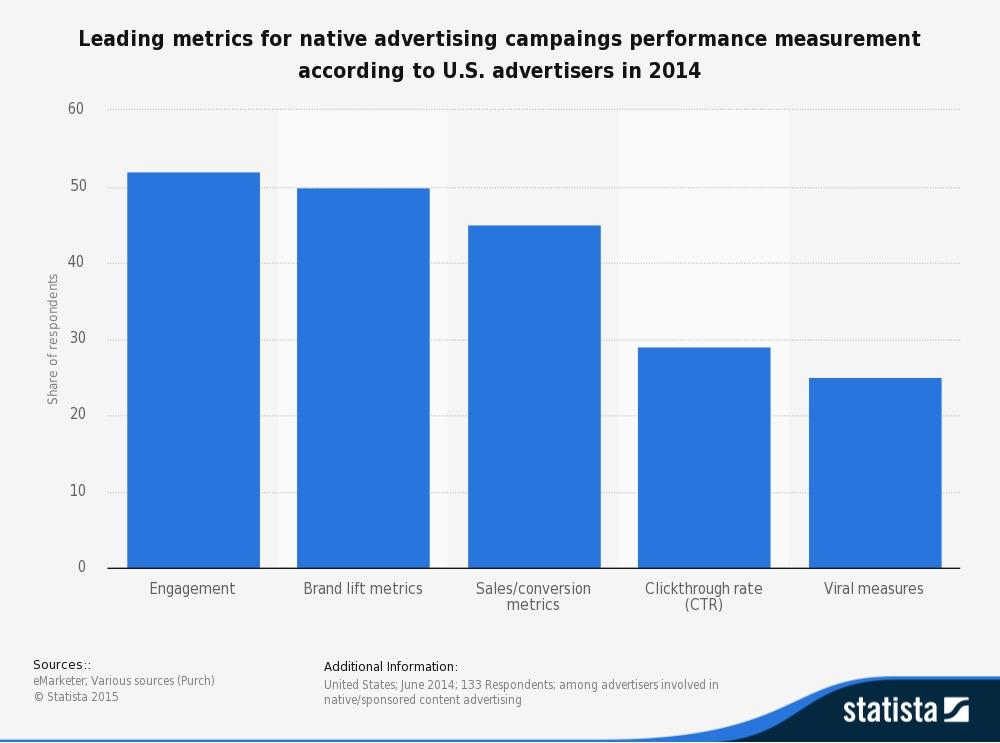

Native advertising spending is soaring based on data from multiple sources that show their superior performance over traditional display, particularly on mobile.

According to Celtra research, native ad formats are by far the best performers among all rich media ads. Engagement rates at 18 per cent, are more than twice that of standard ads. And users spend 40% more time interacting with native ads than they do with standard ones.

With higher engagement and click-through rates, this “new” revenue source is being heralded as a massive opportunity for publishers and marketers alike. So it’s no surprise that most publishers have already jumped on the $US21bn bandwagon.

Native has also been a driver behind the expansion of many publishers’ advertising offerings to include the production of sponsored ads, allowing brands to tap into the publisher’s editorial team’s expertise. Here are just a few…

|

Publisher |

In-house Agency |

|

Condé Nast |

|

|

Financial Times |

|

|

Time Inc. |

|

|

The New Republic |

|

|

Forbes |

|

|

The New York Times |

Lucrative deals are being struck with brands on a regular basis by some top-tier publishers demanding high minimums to produce native advertising.

The elephant in the room

But the move to offer native ad services to brands comes with both a silver lining and its proverbial cloud.

Earlier this year, Contently surveyed 509 male and female consumers over the age of 18 to determine how they interpret native advertising on publisher websites including Forbes, The Atlantic, The Onion and Fortune, to name a few.

Boston Consulting Group (BCG) also surveyed 4,500 people across multiple age groups in the US, UK, Germany and Italy to determine how they perceived branded content.

The good news

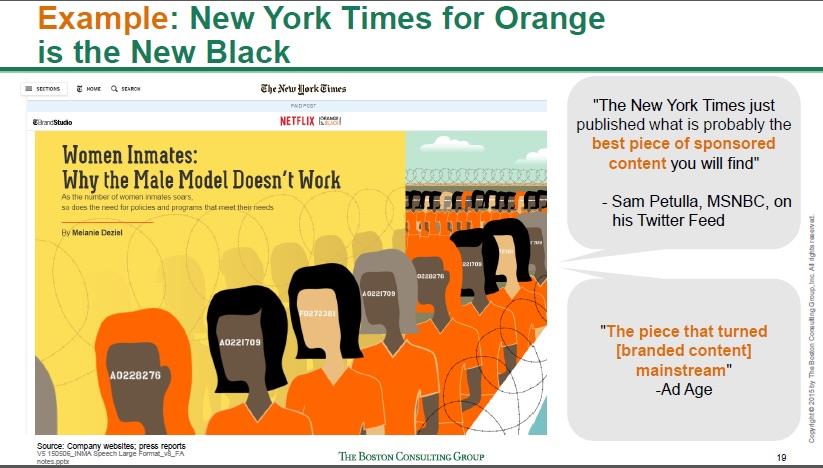

• The vast majority of consumers have encountered, enjoy and seek branded content as seen with the very popular The New York Times’ Women Inmates paid post (BCG)

• Branded content positively impacts favorability and purchase ROI (BCG)

• Consumers are giving media properties permission to play in branded content (BCG)

• Most consumers tend to identify native advertising as an article, not an ad (Contently)

• Native ads consumers consider to be high quality reported a significantly higher level of trust for the sponsoring brand (Contently)

The bad news

• Many consumers have trouble identifying the brand associated with a piece of native advertising (Contently)

• Branded content magnifies negative sentiment among those who dislike the brand (BCG)

The ugly news

• 48 per cent of consumers feel deceived when they realize a piece of content was sponsored by a brand (Contently)

But it’s not just consumers who are wagging their fingers at publishers and advertisers they believe are practicing to deceive them. From John Oliver’s infamous flameout on HBO to strike threats at The Globe and Mail, the purists of traditional publishing aren’t jumping for joy over the trend to go native. They seem to believe that contributing through their editorial and journalistic talents to give readers a better reading experience is somehow a threat to their integrity and the media brands to which they serve.

Is that hubris or is it protectionism or is it a valid concern over the blurring of lines between journalism and marketing? I don’t have the answer to that, but there’s got to be a reason why big brands have been able to lure highly reputable journalists away from newsrooms into content marketing and PR. Brands and marketing agencies want quality advertorial content and they value journalists’ talents to deliver it, unlike many traditional publishers that treat news men and women as disposable commodities.

Regardless of the pushback, however, there is little doubt that this new gravy train has left the station – native is here to stay. Let’s just hope that the perils of the past, don’t predict a parallel future. Let’s not mess this up again!

Abuse, you lose!

According to recent research by the UK Association of Online Publishers (AOP), 33% of consumers are more likely to trust native advertising than traditional advertising. It also found that clicking on a native ad on a premium content website (like your magazine) has greater impact than clicking on a native ad on Facebook. Sounds promising.

But can native advertising save the industry from the spread of what some publishers and marketers believe are digital highway robbers – the ad blockers? Maybe. But only if consumers are kept at the centre of a publisher’s native advertising strategy.

Continue the practice of “serving” native ads like banner ads are done today, rather than “publishing” them with the same care and customer-focused attention done with editorial content and we’ll once again be vulnerable to more than just ad-blocking firewalls; we’ll lose the trust of our most valuable asset – our audience.

Native and Glossy – a match made in advertising heaven

Advertising in most newspapers has most readers snoozing as they’re perusing the content, but in the magazine world, glossy ads are as important to many consumers as the editorial content they surround.

Classifieds once enjoyed that same relationship with readers until publishers ignored warnings as far back as 1992 when Bob Kaiser of The Washington Post wrote a memo to then owner, Don Graham highly recommending that the newspaper “design electronic classifieds now… and seek to become the dominant provider of electronic advertising and information in [the] region.”

Well, we know how all that ended up.

But magazines still enjoy audience engagement through the “Vogue Effect” of glossy ads. And if done right, magazine publishers can capitalise on that relationship even further through well-crafted native ads.

It’s already been done for years in most fashion, lifestyle and technology publications. Open almost any of those magazines and you’re bound to run across a gift guide that is pure native.

When you think “listicle” BuzzFeed probably comes to mind, but magazines have been publishing lists long before Jonah Peretti was a twinkle in his father’s eyes.

From longform articles in Forbes to product endorsements within Elle celebrity interviews and everywhere in between, there are scores of different ways magazines are using native advertising.

![So what is native advertising really? Definitions of what it is and what it isn’t spread far and wide across the web as associations, vendors, publishers, marketers and the media attempt to wrap their heads around this shiny new revenue stream. The International Advertising Bureau (IAB) defines native ads as “paid advertisements that are so cohesive with the page content, assimilated into the design, and consistent with the platform behaviour that the viewer simply feels that they belong.” Sharethrough (a member of the IAB Native Advertising Task Force), calls “a form of paid media where the ad experience follows the natural form and function of the user experience in which it is placed”. Why a promotional practice that has been around for over a century needs a new definition, I don’t get. There’s really nothing new about native advertising, other than its name coined in 2011. Native ads have been served across all forms of medium for decades; we just called them advertorials. Check out this 1914 Cadillac-sponsored “native ad” in The Saturday Evening Post. Except for the layout and use of graphics, there’s not much difference between the past and the present when it comes to sponsored content. So what’s all the fuss about? Why is there so much hype about something we’ve had in our advertising arsenal since long before the dawn of digital? Few would argue that banner blindness is an electronic epidemic for which there is no cure. But are native ads digital media’s last hope to recapture the eyeballs, trust and loyalty of consumers they’ve been abusing for years with poor quality, invasive and overly commoditised banner, interstitial and instream promotions? Maybe… Hope springs eternal Native advertising spending is soaring based on data from multiple sources that show their superior performance over traditional display, particularly on mobile. According to Celtra research, native ad formats are by far the best performers among all rich media ads. Engagement rates at 18%, are more than twice that of standard ads. And users spend 40% more time interacting with native ads than they do with standard ones. With higher engagement and click-through rates, this “new” revenue source is being heralded as a massive opportunity for publishers and marketers alike. So it’s no surprise that most publishers have already jumped on the $US 21 billion bandwagon. Native has also been a driver behind the expansion of many publishers’ advertising offerings to include the production of sponsored ads, allowing brands to tap into the publisher’s editorial team’s expertise. Here are just a few… Publisher In-house Agency Condé Nast 23 Stories Financial Times FT2 Time Inc. The Foundry The New Republic Novel Forbes Brand Voice The New York Times T Brand Studio Lucrative deals are being struck with brands on a regular basis by some top-tier publishers demanding high minimums to produce native advertising. The elephant in the room But the move to offer native ad services to brands comes with both a silver lining and its proverbial cloud. Earlier this year, Contently surveyed 509 male and female consumers over the age of 18 to determine how they interpret native advertising on publisher websites including Forbes, The Atlantic, The Onion and Fortune, to name a few. Boston Consulting Group (BCG) also surveyed 4,500 people across multiple age groups in the US, UK, Germany and Italy to determine how they perceived branded content. The good news • The vast majority of consumers have encountered, enjoy and seek branded content as seen with the very popular The New York Times’ Women Inmates paid post (BCG) • Branded content positively impacts favorability and purchase ROI (BCG) • Consumers are giving media properties permission to play in branded content (BCG) • Most consumers tend to identify native advertising as an article, not an ad (Contently) • Native ads consumers consider to be high quality reported a significantly higher level of trust for the sponsoring brand (Contently) The bad news • Many consumers have trouble identifying the brand associated with a piece of native advertising (Contently) • Branded content magnifies negative sentiment among those who dislike the brand (BCG) The ugly news • 48% of consumers feel deceived when they realize a piece of content was sponsored by a brand (Contently) But it’s not just consumers who are wagging their fingers at publishers and advertisers they believe are practicing to deceive them. From John Oliver’s infamous flameout on HBO to strike threats at The Globe and Mail, the purists of traditional publishing aren’t jumping for joy over the trend to go native. They seem to believe that contributing through their editorial and journalistic talents to give readers a better reading experience is somehow a threat to their integrity and the media brands to which they serve. Is that hubris or is it protectionism or is it a valid concern over the blurring of lines between journalism and marketing? I don’t have the answer to that, but there’s got to be a reason why big brands have been able to lure highly reputable journalists away from newsrooms into content marketing and PR. Brands and marketing agencies want quality advertorial content and they value journalists’ talents to deliver it, unlike many traditional publishers that treat news men and women as disposable commodities. Regardless of the pushback, however, there is little doubt that this new gravy train has left the station - native is here to stay. Let’s just hope that the perils of the past, don’t predict a parallel future. Let’s not mess this up again! Abuse, you lose! According to recent research by the UK Association of Online Publishers (AOP), 33% of consumers are more likely to trust native advertising than traditional advertising. It also found that clicking on a native ad on a premium content website (like your magazine) has greater impact than clicking on a native ad on Facebook. Sounds promising. But can native advertising save the industry from the spread of what some publishers and marketers believe are digital highway robbers – the ad blockers? Maybe. But only if consumers are kept at the centre of a publisher’s native advertising strategy. Continue the practice of “serving” native ads like banner ads are done today, rather than “publishing” them with the same care and customer-focused attention done with editorial content and we’ll once again be vulnerable to more than just ad-blocking firewalls; we’ll lose the trust of our most valuable asset – our audience. Native and Glossy – a match made in advertising heaven Advertising in most newspapers has most readers snoozing as they’re perusing the content, but in the magazine world, glossy ads are as important to many consumers as the editorial content they surround. Classifieds once enjoyed that same relationship with readers until publishers ignored warnings as far back as 1992 when Bob Kaiser of The Washington Post wrote a memo to then owner, Don Graham highly recommending that the newspaper “design electronic classifieds now… and seek to become the dominant provider of electronic advertising and information in [the] region.” Well, we know how all that ended up. But magazines still enjoy audience engagement through the “Vogue Effect” of glossy ads. And if done right, magazine publishers can capitalise on that relationship even further through well-crafted native ads. It’s already been done for years in most fashion, lifestyle and technology publications. Open almost any of those magazines and you’re bound to run across a gift guide that is pure native. When you think “listicle” BuzzFeed probably comes to mind, but magazines have been publishing lists long before Jonah Peretti was a twinkle in his father’s eyes. From longform articles in Forbes to product endorsements within Elle celebrity interviews and everywhere in between, there are scores of different ways magazines are using native advertising. But sadly some publishers have fallen off the tenuous native advertising tightrope. This native ad “editorial” didn’t last long on The Atlantic after a backlash from mainstream media. Other publishers (e.g. Forbes, Bon Appétit) have also been criticised for allegedly crossing the blurry line between journalism and advertising by posting native ads on their cover pages. And it’s not just magazines that are being lambasted for questionable native ad practices. A number of newspapers have been slammed for misleading readers with sponsored content posing as hard-core news. A second chance The promise of native can’t be denied; its pros outweigh its cons if done right. But one must be very careful not to repeat the sins of the past. Today 20% of the content on the Huffington Post is native advertising, and it’s not stopping there. When does it become too much? And what about the rush to program the placement of native ads? Programmatic has value, but like all things that look too good to be true, isn’t it the first step to commoditising native to the point that it becomes the next blocked banner ad? Poor ad quality, lack of transparency and over-commoditisation will be the death of native advertising as ad blockers become more sophisticated in their ability to detect and block native ads. It’s a slippery slope, but we’ve not bottomed out yet. There is still hope to build trust with readers if publishers choose to only publish native ads that: • Deliver real value (e.g. high quality, informative, educational, entertaining, helpful, etc.) • Are contextually-relevant within the surrounding editorial content • Provide full disclosure that the content is sponsored You already do that with the content you provide readers so just put your native ads through the same editorial filters and ask yourself, “Would this ad bring me, as a reader, value? Would I want to share this with others?” If the answers are both yes, then you’ve got yourself a winner. You never get a second chance to make a great first impression, but maybe, just maybe, with an audience-centric native ad strategy you just might get a second chance to create a great user experience that keeps readers coming back for more. ()](https://d1ri6y1vinkzt0.cloudfront.net/media/images/Original/e15ac622-b7ab-4773-85d5-90b562735d73.jpg?v=-1112929821)

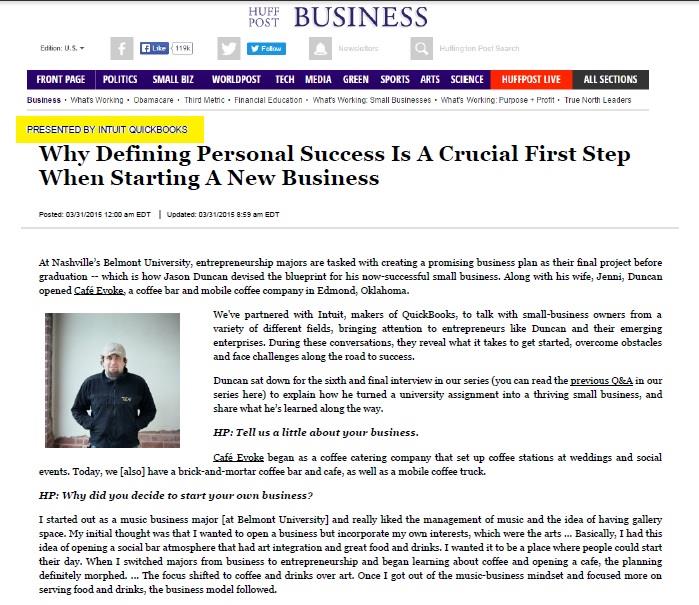

But sadly some publishers have fallen off the tenuous native advertising tightrope. This native ad “editorial” didn’t last long on The Atlantic after a backlash from mainstream media.

Other publishers (e.g. Forbes, Bon Appétit) have also been criticised for allegedly crossing the blurry line between journalism and advertising by posting native ads on their cover pages.

And it’s not just magazines that are being lambasted for questionable native ad practices. A number of newspapers have been slammed for misleading readers with sponsored content posing as hard-core news.

A second chance

The promise of native can’t be denied; its pros outweigh its cons if done right. But one must be very careful not to repeat the sins of the past.

Today, 20 per cent of the content on the Huffington Post is native advertising, and it’s not stopping there. When does it become too much?

And what about the rush to program the placement of native ads? Programmatic has value, but like all things that look too good to be true, isn’t it the first step to commoditising native to the point that it becomes the next blocked banner ad?

Poor ad quality, lack of transparency and over-commoditisation will be the death of native advertising as ad blockers become more sophisticated in their ability to detect and block native ads.

It’s a slippery slope, but we’ve not bottomed out yet. There is still hope to build trust with readers if publishers choose to only publish native ads that:

- Deliver real value (e.g. high quality, informative, educational, entertaining, helpful, etc.)

- Are contextually-relevant within the surrounding editorial content

- Provide full disclosure that the content is sponsored

You already do that with the content you provide readers so just put your native ads through the same editorial filters and ask yourself, “Would this ad bring me, as a reader, value? Would I want to share this with others?”

If the answers are both yes, then you’ve got yourself a winner.

You never get a second chance to make a great first impression, but maybe, just maybe, with an audience-centric native ad strategy you just might get a second chance to create a great user experience that keeps readers coming back for more.

More like this

An announcement for those who said native advertising couldn’t scale

Native advertising as we know it isn’t sustainable

Download Innovation 2015 chapter: Will native advertising save or kill your brand?