Facing facts: How AI can help the media hold politicians to account

As US presidential candidates Kamala Harris and Donald Trump traded verbal blows in one of the most consequential political debates in American history this week, media fact-checkers hung on every word.

CNN’s website – which has a dedicated Facts First searchable database reminding readers that “there is no alternative to a fact” – told its users whether claims on everything from inflation figures and fracking to immigrants eating people’s pets were accurate.

The high-profile debate was, of course, just the latest part of the US election monitored by fact-checkers, with legacy media brands like The Washington Post, the BBC (through its BBC Verify initiative) and The New York Times keeping a close eye on interviews, campaign rallies and online claims about the candidates.

In an age of “fake news” and “alternative facts” where misinformation can swing elections, sow division and even cause riots, having the media shining a light on the murky remarks of politicians and their followers has never been more important.

“Public debates between candidates seeking office offer the capacity to promote an informed electorate. But the educational value of debates can be corrupted by erroneous and misinformed assertions advanced by the candidates,” The Hill contributor Arthur Eisenberg recently wrote in an op-ed extolling the virtues of real-time debate fact-checking.

“During candidate debates, claims are often made which are not entirely accurate. In the heat of the moment, candidates occasionally exaggerate. Some may do so more than others. Some may even do so intentionally.”

Jonathan Este of The Conversation pointed out earlier this year that informing the public is only one way fact-checking can make a difference.

“Research confirms what many fact-checkers see firsthand: knowing someone is checking will often push politicians to be more careful with their claims.

Obvious exceptions aside, many public figures will quietly drop a claim after it’s been debunked – or even issue a mea culpa.”

With fact-checkers now so important to media organisations they share the spotlight with political correspondents – CNN’s Daniel Dale assessing the debate performances of Trump and Harris live on air – the question is not whether debates, speeches and online claims should be carefully monitored, but how it can be done more efficiently. And that, research shows us, is where AI is starting to make a difference.

A helping (robotic) hand

This year’s Innovation in Media World Report – which explores the most profitable developments impacting media today and is authored by Jayant Sriram and Juan Señor of Innovation Media Consulting in partnership with FIPP – reveals how publishers are embracing new technology when it comes to fact-checking.

The report shows that nearly 90% of respondents in a global survey carried out by POLIS, the journalism think tank at the London School of Economics and Political Science, reported using AI for tasks such as fact-checking, proofreading, trend analysis and generating summaries. And there is plenty of new tech for the media to try out.

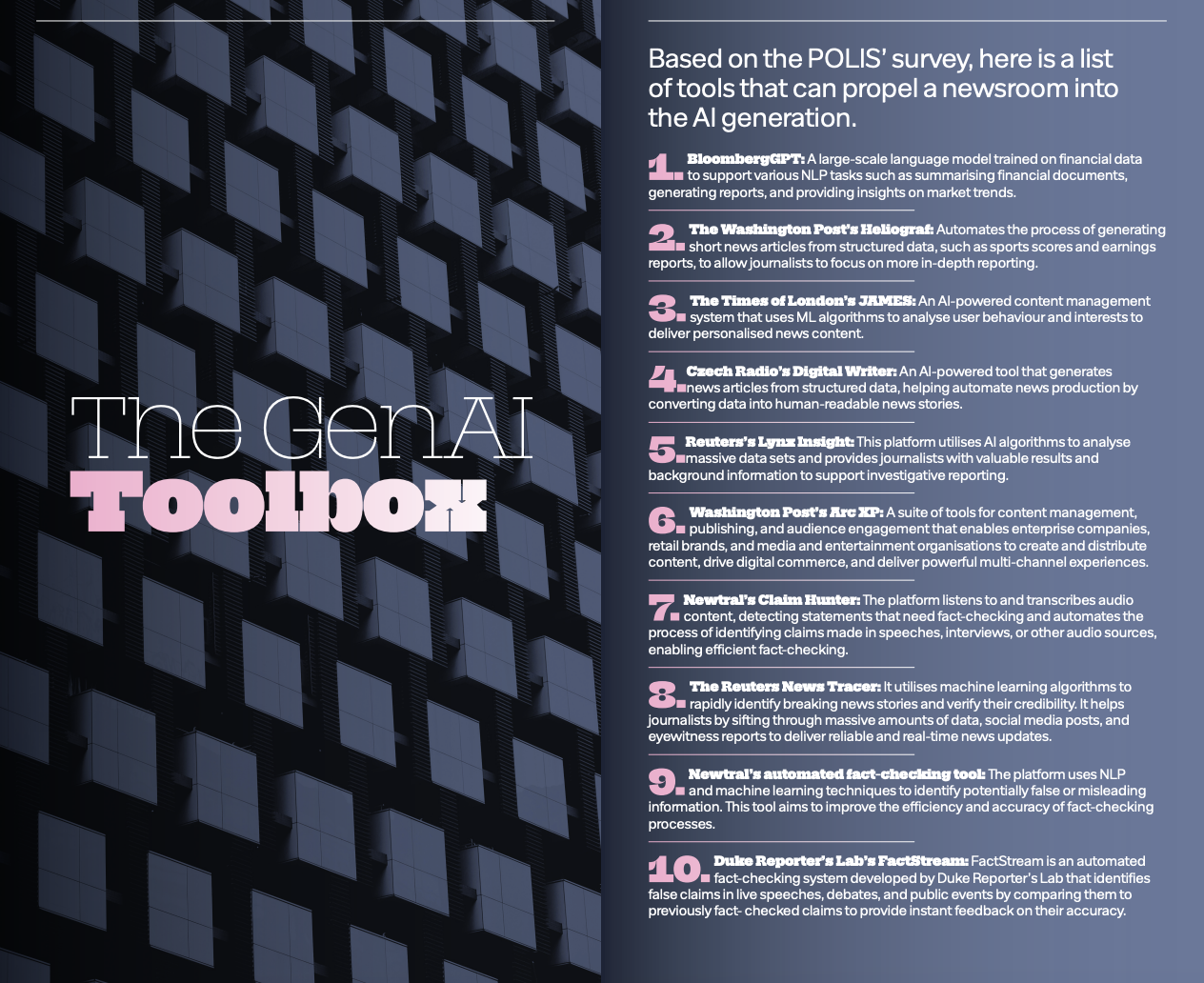

Tools propelling newsrooms into the AI generation includes Duke Reporter’s Lab’s FactStream – an automated fact-checking system that identifies false claims in live speeches, debates and public events by comparing them to previously fact-checked statements to provide instant feedback on their accuracy.

Newtral’s ClaimHunter is a platform that listens to and transcribes audio content, detecting statements that need fact-checking and automates the process of identifying claims made in speeches, interviews, or other audio sources, enabling efficient fact-checking.

Newtral also has an automated fact-checking tool that uses NLP and machine learning techniques to identify potentially false or misleading information and improve the efficiency and accuracy of fact-checking processes.

The Reuters News Tracer utilises machine learning algorithms to rapidly identify breaking news stories and verify their credibility. It helps journalists by sifting through massive amounts of data, social media posts and eyewitness reports to deliver reliable and real-time news updates.

Prominent UK fact-checking organisation Full Fact developed an AI-powered tool to combat fake news during the UK general election. Initiated in 2019, the tech, which sifts through vast amounts of data to help identify misinformation prevalent in public debates, has gained traction among various subscribers, including fact-checkers in South Africa, Nigeria and Australia.

The tool also tracks the repetition of false information online or by public figures, highlighting the challenge of combatting fast-spreading misinformation.

“It’s like trying to build an immune system,” Mevan Babakar, Project Manager at Full Fact in London told the Innovation Report. “As more information goes out into the world that is wrong, what we don’t have is the means of pushing back.”

Kate Wilkinson, Senior Production Manager at Full Fact, told PoliticsHome that the AI tool relieves fact-checkers of the burden of monitoring and identifying claims, allowing them to focus on analysing context, consulting experts and communicating their findings.

“A lot of our work is not just fact-checking, but actually actively campaigning, advocating and engaging with politicians, MPs and people in positions to correct the record when they have made an error,” she said.

“The tool flags those repeated falsehoods, so that we are able to understand how misinformation is spreading, who is amplifying it and how it’s changing, but then also act to change the ecosystem that allows that misinformation to flourish and be shared.”

A double-edged AI sword

While artificial intelligence certainly presents a solution to misinformation, it is also very much part of the problem. When it comes to bad content new tech is both shield and sword, arsonist and firefighter.

The emergence of AI and “deepfakes” has, after all, complicated the fight against misinformation. Concerns persists over AI’s gender bias and the inaccuracy of Large Language Models, with leading Artificial Intelligence researchers at the Oxford Internet Institute warning that LLMs pose a direct threat to science, due to so-called ‘hallucinations’ (untruthful responses), and should be restricted to protect scientific truth.

Despite certain drawbacks, AI has moved well and truly into the mainstream as larger publishers cut deals with the tech platforms and find innovative ways to improve their workflows and processes, as well as reach and engage their audiences through new tech.

With media leaders thinking carefully about their approach to harnessing AI, Damian Radcliffe, Carolyn S. Chambers Professor in Journalism at the University of Oregon, stresses the importance of having a proper AI strategy in place in the Innovation Report.

“Avoid impulsive decisions. Despite the hype around AI, media leaders should not rush to adopt new technologies without a clear strategy,” he says.

“Plan strategically and take time to define how AI can contribute to long-term goals and success metrics. Also, establish a task force. Create internal teams to evaluate AI risks and benefits and learn from past mistakes of rapid adoption.”

There have also been words of warning from the Reuters Institute that, while Generative AI is already helping fact-checkers, it’s proving less useful in small languages and outside the West.

According to the UK-based research centre, newsrooms in smaller markets or markets with minority languages often question whether AI tools are accurate enough to help in their fact-checking efforts.

“We like to think that our understanding of the nuances in the different countries in the sub-region should help us in building tools that are more tailored in tackling the problem of misinformation and disinformation,” Rabiu Alhassan, founder and Managing Editor of GhanaFact, a news fact-checking and verification platform in Ghana, told the Reuters Institute.

“Looking at the way AI is being deployed, we feel it will not do enough justice in either producing content or providing the nuances expected when doing fact-checks. These limitations come from the way these machine learning tools are built.”

![[New!] FIPP Global AI in Media Tracker – November 2025](https://www.fipp.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/articles-header-800x760.png)