Building moats and bridges: AI webinar explores the perils and opportunities that come with media website scraping

Successfully navigating the rise of artificial intelligence is a priority for everyone in the media industry, from large legacy groups to small B2B publishers. And no AI issue is more of a pressing concern than tech companies scraping websites for data to train LLMs. As media groups continue to grapple with the leaking of their lifeblood, FIPP and the PPA recently held a webinar unpacking how content is being used by AI systems, and what publishers can do to both protect themselves and unlock new value and opportunities.

Joining FIPP CEO Alastair Lewis and Sajeeda Merali, the CEO of the PPA, for an online event featuring revealing new statistics and bold strategies, were Paul Hood, an independent consultant and AI advisor, and Lucky Gunasekara, Co-founder and CEO of Miso.ai, an AI lab that has carried out exclusive research into website scraping on behalf of FIPP and the PPA through its Sentinel team.

“The research and the insights that Miso.ai have done lay out very clearly some of the real issues that we as an industry and as publishers need to address and to keep on looking at,” said Lewis. “But equally there are just as many, and hopefully more, opportunities and reasons to be optimistic.”

The webinar arrived at a time when AI is ushering in an era of “liquid information” according to Gunasekara. “Those of us that have worked in newsrooms are used to solid media – you publish an article, a book, a video, a podcast, a newsletter and they are solid linear pieces of media that you’re supposed to read from the beginning to end as the author intended,” he pointed out.

FIPP members: view the webinar video here

“But with AI, these pieces of documents or media files are becoming liquid. We’re basically vaporising them and taking the information encoded within and presenting it to a user or reader directly in the context of the questions they’re interested in, their preferences and things you know are on their mind. This is the big shift that AI is really driving forward. And it’s a gigantic reset of the information and economics of the entire world, potentially.

“That’s why we’re seeing this turf war between all of these different tech titans with trillions of dollars at stake and the question mark is, how is media going to get entangled within it? Part of the answer is that these platforms are extremely data hungry. AI is driven by scaling laws – the more data you train on, the more powerful the models you get and the more dominant you can become as a leader in your space.”

With companies like OpenAI increasingly investing in product experiences, having a close relationship to publishers is of vital importance. “It builds a better product experience because you see trustworthy sources in those products,” said Gunasekara. “And part of the argument that they’ve made to publishers, amongst others, is that by partnering you can get access to tech, royalties and traffic. It’s the mindset you see in the AI community today.”

Miso.ai champions a different mindset, building a tech platform for liquid AI so that publishers can control their data and models and extract the value directly. They do this through Answers, an AI mediated answer service that delivers what readers want from a publisher’s content: responses that are expertise driven, citation-backed and fact-checked.

“Our goal is to drive a decentralised network – one where we’re not setting the rules or controlling the outcomes for publishers, but they’re actually able to build up their own agency and directionality that’s on their terms and for their benefit.

“By building this out, you start to build what’s called a Fediverse. You build this decentralised network of media and knowledge, and that by doing this, we’re effectively squaring the original sin of AI, which is that it’s trained on stolen work, that this technology at a fundamental level Is based on scraping and stealing content to train these models. This is an attempt on our part to try to reconcile that.”

AI and many other topics relevant to current and future of media industry will be further explored at the FIPP World Media Congress, taking place in Madrid, Spain, from 21-23 October 2025.

FIPP WORLD MEDIA CONGRESS

An unforgettable gathering that will shape the future of media.

The birth of Sentinel

Miso.ai launched Sentinel after a discussion with publishing partners in the UK in December last year about the AI Opportunities Action Plan, the UK government’s roadmap to harness the potential of artificial intelligence. One of the arguments that came up was that the government was proposing an opt-out mechanism by which publishers can say they don’t want their content used in an AI product.

“This sparked the question mark: Do we already have standards for how AI companies could respect publisher content? And we do,” said Gunasekara. “It’s called robots.txt – a web file we all publish in terms of our websites and has directives encoded within for what bots are allowed and which bots and directories are prevented.

“It’s basically a do not enter sign that includes a list of which bots you don’t want to go on your website and collect your information. So, we realised that with Sentinel as a system, we could build it up so that we look at robots.txt and we see how AI companies are complying or not complying to these requests.”

After building up a database of publishers and focusing, initially, on free AI-powered answer engine Perplexity, Miso.ai has essential constructed an open service for publishers to check if their data is being scraped.

“It is effectively a form of disclosure by reversing the logic – if they are scraping publishers, then we are scraping them to understand what publisher content they are actually being built on,” said Gunasekara.

Attack of the shadow bots

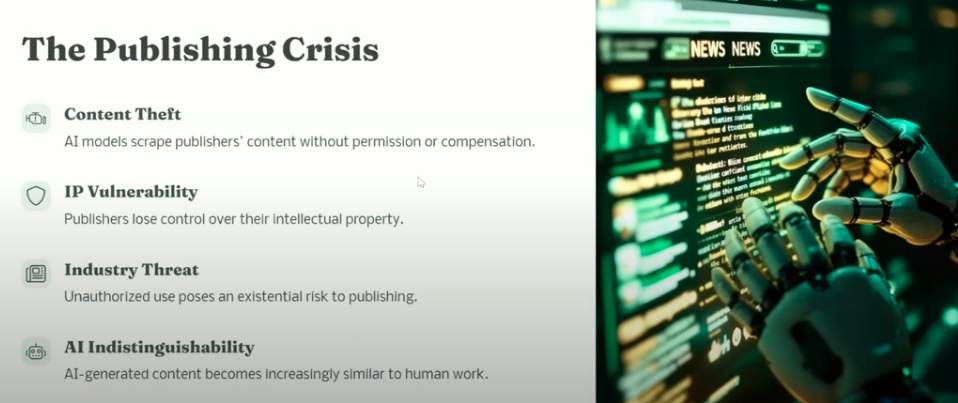

Through Sentinel, Miso.ai soon discovered that an “army of shadow bots” were targeting publisher websites. These include commercial bots that sell the data, big foundation labs and even a pet project by an engineer at Google in France. Overall, Miso.ai found that 1,300 unique bots were targeting 2,700 publisher robots.txt files.

Adding to the problem is the fact that publisher blocking rates are very low when it comes to robots.txt. The publishers monitored by Miso.ai on average only target 15 bots, while there are around 75 bots of interest to actually target. Meanwhile, only 15% of publishers are opting out of Google-Extended, which gives Google permission to train on their content.

“When the average blocking rate is only 15 bots it leaves publishers very vulnerable to different forms of data collection and model training,” warned Gunasekara. “There is this land grab of data these bots are initiating, but it’s happening so fast that we really need a lot of active intelligence as an industry to know which bots are out there, who’s on the radar, who’s blocking what and what’s the most successful list to target.

“Not adopting this is just leaving open windows and doors for bots to come in, scrape and collect your data and train a model. One of the core things that we’re primarily concerned about is these models are substitutional to an effect and corrosive to the news industry.”

While there is a counter argument from some publishers that blocking the bots will cost them referral traffic, research has found that chatbots send on average 96% less traffic out to sources than a traditional Google keyword search.

Further bad news is that there is very little respect for publisher robots.txt files. Of the 1,300 publisher that are part of FIPP, NLA or PPA who in their robots file tried to block Perplexity, there was a 15-20% article violation, a 65-77% homepage news violation and 35-66% image violation. Most concerningly there are also paywall violations.

Miso.ai found that smaller niche publisher are impacted more by image violations while bigger media groups are more likely to suffer article violations.

Perplexity not only relies on their own web crawlers but using third-party web-crawlers. “This means there’s this hidden network of relationships that we don’t see right now between these organisations,” said Gunasekara. “So, you as the BBC may tell Perplexity – do not crawl, don’t scrape please, we don’t want to be in your service. But if you don’t know the groups that are working with them, they will still go to your site, collect the data and then license it over to them. That is why disclosures are so critical.”

To find ways to fight back against scraping, Miso.ai sought advice to publishers that have been largely successful at blocking Perplexity. They found that these particular media groups have huge robots.txt files and really stay on top of updating them. Media companies have also increased their investment in bot-blocking software, while sending out cease and desist letters is another option.

Keeping out the vampires and werewolves

Looking ahead, Gunasekara pointed out that the open web is breaking down. “We are in a period between the old world and the new world in terms of information systems that is becoming a free for all,” he said.

“There are the institutionalists who would say, we should set new ground rules with these organisations and work with them. I do understand that, but I think there’s a growing number of these groups that just don’t really obey the rules-based order and think that engaging in the rules-based architecture is actually a weakness and there’s opportunity to be found in operating very differently.

“This unfortunately might mean that it’s not about who you block but who you let in and that we’re moving away from the open village model of the Internet and much more towards castles, moats and draw bridges. And that’s unfortunately because if you don’t do this, werewolves and vampires will come in at night and eat your villagers. This is kind of the real decision point that we’ll have to make as an industry.”

Gunasekara believes bot blocking and vigorous legal actions will eventually lead to a very different architecture for the web. “We’re seeing more and more groups actually build their own systems and monetise them directly,” he said.

“Publishers are building their own AI systems directly as their own core reader-facing service, and this is actually yielding really good results. They’re finding much higher search engagements, they’re driving higher page engagement, they’re driving registrations, they’re driving subscriptions.

“As this landscape of sites grow, we’re going to start to see an opportunity over time for a very different web, which is much more agentic. And this is the thing that I’m optimistic about. As more and more groups start building their own infrastructure by which they can drive reader engagement, they’re also building the architecture and infrastructure for them to integrate with other services directly.

“And I think that is the directionality for publishing and media we should be encouraging here. It’s not that you let people take all your data and let them decide what they’re going to do with it, but you build your own agency and your own infrastructure.

“You say, hey, if you want to know what I know about a topic, I’m happy to tell you and my agent will tell you, but I want to know what you’re asking, I want you to know what I shared, I want you to tell me what you actually presented to your user and I’d like to know the click-through rates and the royalty calculation please. These types of protocols are emerging right now. The platforms are realising they will have to move in some sort of direction like this and there is a lot of opportunity.”

Constructing a framework

For PPA Chair Sajeeda Merali, who has been leading the UK creative industry’s AI conversations with the government, the AI scraping issue comes down to protecting copyright. She pointed out that a gold standard law protecting publishers from their content being used without permission has been in place in the UK since 1709. The law grants the copyright holder the rights and tries to move the burden of respecting those rights to the people who are seeking to reuse that information.

“It’s a law that has been in effect and stood strong through a number of changes in the digital landscape,” she pointed out. “Now, the AI tech platforms are pushing government to allow their models to train on copyrighted material. They’re arguing that fair use exemption applies to this, and this is needed to ensure growth of the AI economy, and they are supportive of deregulation.

“The creative sector is challenging this assumption. We believe that fact-checked original content is a really critical part of that growth and that is something that we really need to think about sustaining. We believe that deregulation isn’t the only viable path here, so we’re asking government to consider how a balanced regulatory approach could actually provide the UK with more of that competitive edge.”

In February the UK government cited four options in its AI consultation: One that suggested doing nothing; one enforcing copyright that allows publishers to decide how they opt in and how they agree terms (favoured by the PPA and many of the other parts of the creative sector); a broad exception which removes copyright entirely; and a narrower exception (favoured by the government) where it removes the rights and creators had the option to opt out.

“Obviously, based on what Lucky has just shared with us, the last one is not really a viable option because it’s not being respected at the moment,” Merali said. “A key part of this is to understand how we get the best environment for the creative sector to be sustainable.

“The thing to remember is that the UK has proportionately a much bigger creative sector, and so there’s a lot more to defend and lose by abandoning copyright protections completely. This isn’t really about copyright versus AI. Many of our members see this as that we need to find a way of emerging smart technology to go hand in hand with the sustainability of the creative sector.”

Merali also stressed the importance of a having a framework that has transparency and pays content creators fairly.

“Transparency is quite essential because it’s going to create the conditions that are going to incentivise licensing. We’re talking about technology here that can make automated decisions based on the info and data and training that it’s had. And if we don’t believe that our developers know what data is going into that technology – that’s negligence, right?

“So, all we’re asking for is that there is transparency about that. There’s no added cost to that sort of thing. It’s the same as what would be required in any regulated industry so it’s quite a reasonable ask.

“And then when it comes to paying content creators fairly, models exist. Apple News has set a precedent of about 50/50 revenue share. So, there needs to be collective or individual agreement in order to use that content and that’s the environment that we’re seeking to create in the UK.”

Scrambling the fighter jets

According to independent AI consultant Paul Hood, the gap that has been left as the industry waits for a sustainable framework is concerning.

“It’s the gap smaller publishers in particular are really concerned about because we know that, especially in Silicon Valley, this kind of attitude they have of moving fast and breaking things, often that could mean moving fast and breaking law,” he said.

“Then the momentum gathers its own pace and it’s really difficult for the regulatory framework to catch up. And as we’ve seen, the genie’s out the bottle and it’s too late. So, there is an urgency here.”

Hood lamented the fact that, historically, media companies have not been great at collaborating and addressing a common concern.

“Publishers are like a box of fireworks – they can be all neatly stacked together, but when you want to do something, you obviously have to light a firework and then you’ve got fireworks going in a million different directions and that really epitomises the problem,” he said.

“The longer term solution is this framework and regulation and we’ve got to campaign for that, but in the meantime there’s this gap and I think there’s an opportunity for publishers, a few of them, to take action and to effectively lead the way.”

Hood turned to a war-time analogy to rally the media troops for a ‘Digital Pathfinder Project’.

“My granddad was a rear gunner in a Lancaster bomber in the Second World War. The success rate of Lancaster bombers was really low. They got shot down. They were like these lumbering giants heavily laden down with bombs. These waves of bombers were just getting shot down all the time.

“What broke that cycle of heavy losses was the deployment of something called Pathfinders – much smaller, lighter aircraft that would fly ahead and drop coloured dye bombs, essentially, that would allow the Lancaster bombs to be much more accurate. The Pathfinders was a much smaller group of highly skilled, highly courageous, bold pilots who made the mission much more accurate.

“And I think that’s what we need here. We need a Pathfinder project. I think we need a few brave publishers to get together to become the pathfinders.”

Hood believes that to get a framework where there is transparency around licensing and fair compensation for publishers, the industry, in the short term, need secure data clean rooms where publishers can experiment.

“I’ve spoken to five or six publishers who have said, look we’re willing to get some data, we want to be part of that Pathfinder mission to feed back to Mission Control and be part of the solution,” he said.

“We have to have a system that’s completely transparent and completely independent so that publishers can be assured that with this experiment, there’s nobody with any vested interest in it. The only vested interest is getting the data out to help the bigger markets and the industry bodies to strengthen their case, whether that’s lobbying the government or going to Big Tech.”

According to Hood, blockchain can play a crucial role in transparency by fingerprinting and watermarking content on the way into the clean room so that multiple publishers can experiment.

“The idea is that AI developers can then come to that data cleanroom and license content for chaining their models. You’ve got provenance, you’ve got tracking and you’ve got transparent ledgers,” he pointed out.

“That would lead to what we hope is some utopia – new revenue streams, making sure our IP is protected and tracking across all of the areas where our content may then be used.”