How Ghanaian journalists cope in era of fake news and influencer news aggregation

It’s that time of the year again when fake news is rife in Ghana.

With just under five months to the presidential and parliamentary elections, social media has become the most potent tool for smear campaigns and the spreading of misinformation and disinformation.

Although the polarisation of traditional media has seen the watchdog role of the press wane slightly, there’s still at least some form of professionalism and editorial control on radio and television platforms. On social media, however, there’s none, and the consequence has been a rise in “influencer news aggregation.”

As this relatively new term suggests, it’s here that almost every influencer doubles as a news aggregator because it seems to be the quickest way to build a large following. While news aggregation in itself is no bad thing, the problem is that many in such spaces merely want to drive engagement with their pages, hence the rush to post breaking news without fact-checking, as well as deliberately sensationalising.

The most common is around entertainment stories, where you’d sometimes find a social media account with a huge following ascribing a misleading lead-in to a video with a completely different context. And with the presidential elections in Ghana also nigh, “bot accounts” affiliated to the ruling New Patriotic Party (NPP) and the opposition National Democratic Congress (NDC) have also sprung up, ostensibly to amplify the messages of their political parties, smear their opponents with concocted quotes, and abuse journalists who criticise their respective candidates.

“What I have a challenge with is how they [aggregators and bot social media accounts] misrepresent some of the news they pick from critical media houses,” says Evans Aziamor-Mensah, a journalist with The Fourth Estate, one of the most vibrant investigative media organisations in Ghana. His concerns are also echoed by Kwaku Krobea Asante, who works with Fact-Check Ghana, an organisation that specialises in accountability journalism and also ensures that fake news doesn’t thrive.

Asante believes social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter (X) have enabled the rise of these influencer aggregators to the detriment of proper journalism due to how their algorithms are skewed. “Currently, the algorithms of the digital platforms are gradually shifting away from the news platforms – that is hard news and political news – because people are beginning to get fatigued and tired of the hard news. And this is actually insight from Reuters Digital News Report.”

He continues: “So Facebook and Twitter (X) now favour what we consider as the content industry – content creation industry, let me put it that way. There’s a whole new industry emerging on these platforms and the algorithms are now towards them because they produce very interesting, very controversial content that people generally gravitate towards.”

No different to the rest of the world, the media landscape in Ghana has of course evolved over time. Here, there was an era when those who worked in print media were the most revered, but in recent years much acclaim has gone the way of broadcasters. To this end, comparatively, radio or television journalists tend to earn more than those who write for the websites of the same media houses. Meanwhile not many newspapers are profitable enough to be able to pay their staff well. It all means that the quest for numbers sees vocal “influence” is more likely to land a job on radio or TV than a trained journalist without a large social media presence.

Generally, though, the average journalist in Ghana has challenges that border on poor remuneration and a lack of proper welfare. It is why supposed journalists are now signing endorsement deals as brand ambassadors and taking up roles as mouthpieces of companies that are ready to pay them well – all acts that encourage biases and go against the ethics of the profession.

“Working conditions of journalists is a collective responsibility,” Albert Kwabena Dwumfour, president of the Ghana Journalists Association (GJA), rallied in February. “All stakeholders should look at improving the situation to ensure professionalism. Journalists need to be paid well. The media deserve better… journalists deserve good remuneration,”

More than just poor welfare, there is also the threat of physical harm, especially around those whose work demands they expose politicians and other influential people. While Ghana has long been lauded for its impressive press freedom since switching from military rule to democratic governance in 1992, those gains have been eroded in recent years, with the country performing poorly in the global press freedom rankings by Reporters Without Borders. The latest World Press Freedom Index published in March 2024 found that there has been a rise of partisan media outlets owned by politicians, which skew content and fuel political bias.

The report highlighted the government’s influence on the National Media Commission and noted that “journalists’ safety has seriously deteriorated in recent years.” It added: “Politicians have also made death threats against investigative journalists. Most cases of police violence against journalists are not pursued.”

To date, the assassination of Ahmed Saule, one of the undercover journalists who led an investigation into corruption in Ghana’s football, remains unsolved. There is also the incident of some supporters of the ruling NPP storming the studios of UTV to attack a host and panellists during a live broadcast. Such incidents deter fledgling journalists from venturing into the realm of investigation for fear of harm. And, for the few who defy this reality to demand accountability from those entrusted with power, they are usually frustrated by the system as politicians, especially, find various ways to circumvent the Right to Information law.

“It’s an era where most of the guys in leadership do not really want to release information,” says The Fourth Estate’s Aziamor-Mensah. “It’s difficult, particularly when most of the sources who can help you with credible leads are not willing because of victimisation. And this has become even more pronounced over the past four or five years. I would like to say that one of the ways we’ve been able to get information, we don’t necessarily have to go undercover, is to use the Right to Information law, where we put in the request to help us to complete our stories. But some of the public officials have found cunning ways to hide the information or use the exempt clause within the law.”

The frustration and sometimes intimidation that comes with practising proper journalism in Ghana is why many are gravitating towards the safer side of media in recent times. News aggregation by influencers is fast becoming a new “branch” of the trade and, because of the lack of editorial control on social media, fake news has become rampant.

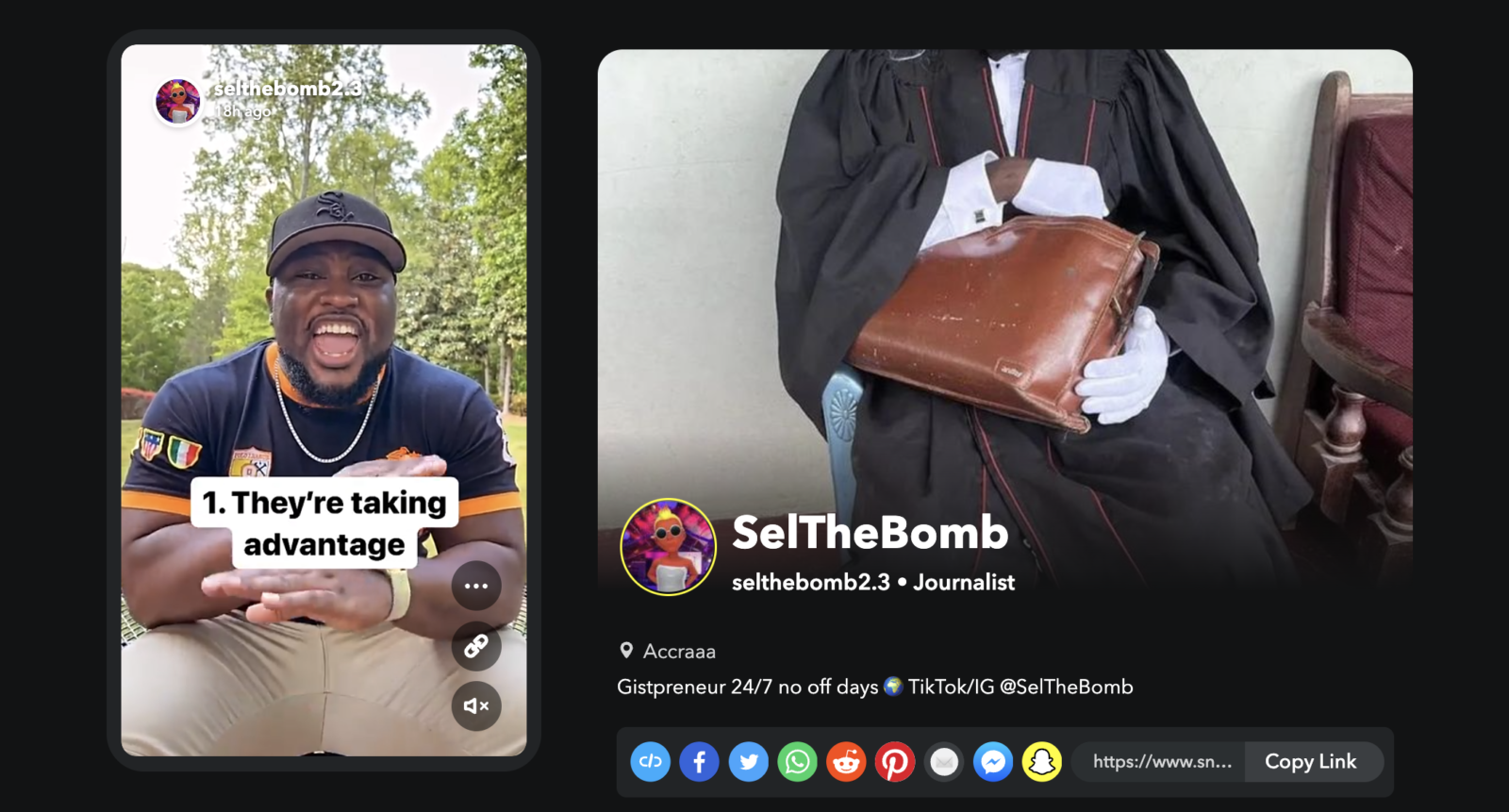

SelTheBomb, a pseudonym, is one of the biggest Snapchat accounts in Ghana and is into news aggregation. (For the purpose of this article, we’ll refer to the gender of the owner of the account as “they” as they insisted on being anonymous). The account describes its operations as being “into spilling the tea in terms of celebrity gossip or getting exclusive information about things that are going on in the country that others don’t have the privilege of getting to know.”

They insist they’ve broken several stories on their Snapchat account before the mainstream media even got wind of them. According to them, they broke the news of the passing of the wife of former president John Agyekum Kufuor and were also the first to acquire exclusive photos from the wedding of media personality Berla Mundi, even though there was a strict “no phones” rule at the event.

Explaining how they source their stories, Selthebomb says: “We have inside sources and sometimes, let me give you a spoiler, some of these celebrities are the sources to their own stories. And apart from that, sometimes you just observe, put pieces together and then you get the information. So you don’t necessarily have information, you don’t necessarily have a source, so it is more like analyzing bits of information out there and then when you piece it together, you get the real thing.”

Amidst concerns that social media news aggregators are taking over the journalism space, Selthebomb believe although they started as a mere aggregator account, what they practice now also constitutes journalism. According to them, when they get a story wrong, they are quick to retract and apologise. More than just seeking out sources, they said, they value their credibility and, therefore, are committed to verifying information before putting it out.

“It started as just aggregating. So you gather the audience, then it gets to a point that you can become a credible source to other news platforms or bloggers. At that point, then it transformed into journalism in a way because the information comes to you first so you have to craft it and put it together. So verifying the information, crafting it and putting it together… in a way I see it as a form of journalism.”

Asante, however, believes his work as a fact-checker is made more difficult by the rise of social media aggregators. He is also wary of the fact that some traditional media platforms are beginning to copy the formats of content creators, thereby putting social media engagements ahead of proper journalism.

“Most of the traditional media houses are now represented on social media, they have pages on Facebook, Twitter (X) and Instagram,” Asante says. “Previously, you would go there and find proper journalism posts, you will not find anything trivial. But these days they also have to match up and get the engagement. They might post a documentary on COVID vaccines, and you’ll go there and then you see probably 10 likes but let them put something controversial, put something graphic over there,

with probably a question that is not even important, to national discussions and you’ll get thousands of engagements.”

Aziamor-Mensah concludes: “For me, there’s no way anybody can convince me that we need to have social media influencers to be able to keep the numbers game. There are some people who still follow what we do and our numbers have grown. I think that’s the best way to go, particularly as we are a third-world country, we’re not growing and we need journalists to hold people accountable.”