“We’ve probably played a big role in making environmental journalism sexy”: Oxpeckers Center founder and editor Fiona Macleod on a decade of pioneering work

When it was established in 2012, the Oxpeckers Center for Investigative Environmental Journalism was Africa’s first journalistic investigation unit to focus on environmental issues. Supplementing traditional investigative reporting with a heavy emphasis on data analysis and geo-mapping, Oxpeckers is a model example of how digital media can use these tools to make journalism stronger – and more interesting.

Now in its 10th year, Oxpeckers has won a slew of top media awards including from CNN, the Asian Environmental Journalism Awards and the China Environmental Press Awards, and is an established leader in the environmental journalism space. It is well respected for its impactful investigations, the methodologies of which have been replicated in different countries around the world.

Reportage by Oxpeckers associates is not only revelatory but has changed laws, policies and lives. It is credited with promoting a ban on canned hunting in Botswana and helping to shape laws on trade in rhino and other wildlife products in China and Mozambique. In South Africa, the work of journalist Mark Olalde on mine closures was discussed during parliamentary committee meetings and has resulted in amended regulations around mining activity.

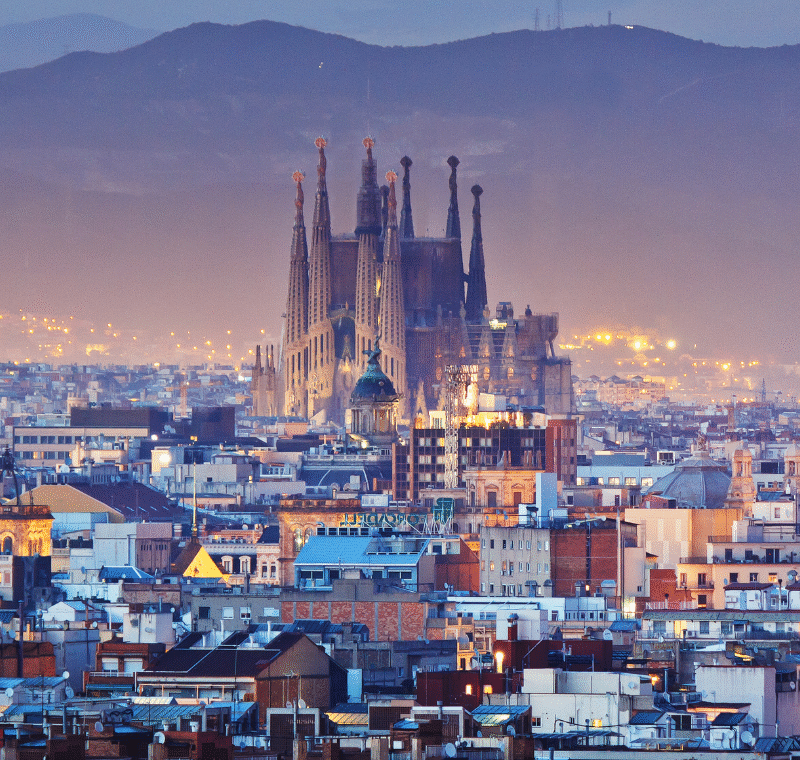

In recent years, the nonprofit has expanded into Asia and Europe and continued to expose a broad range of eco-offences, from wildlife trafficking to the misuse of protected areas.

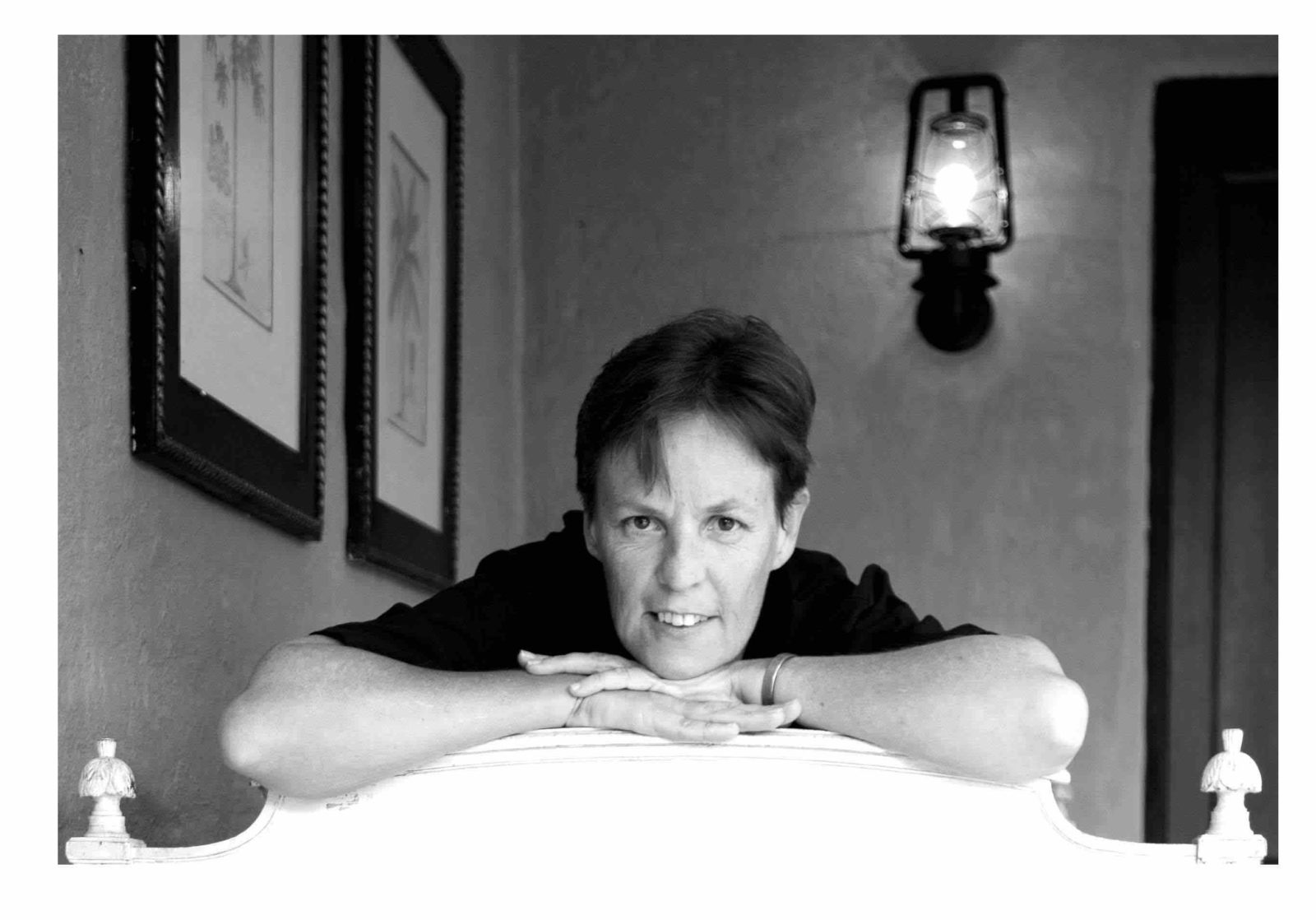

One might expect that such an effective operation would require a large team. And yet, it is still run by a core of just two committed staff: founder and editor Fiona Macleod – an award-winning journalist in her own right, recognised by SAB EnviroMedia for her work in multimedia, print and online – and longtime office manager Anne Driffill. They work from a small town near Kruger National Park, famous for rhinos and other endangered animals, in South Africa.

I spoke with Macleod recently over Zoom, where she told me more about Oxpeckers’ origins, its illuminating investigations, the legacy they are hoping to build, and how environmental journalism has changed in the past decade.

An opportunity to use modern tools

Before founding Oxpeckers, Macleod was a seasoned environmental journalist, having worked as environmental editor at the Mail & Guardian newspaper in South Africa for 10 years. She has also won many awards, including the prestigious Nick Steele award, acknowledging her contributions to environmental conservation.

But around the year 2012, in the midst of a constantly shifting media ecosystem, she saw a gap opening up in her specialism.

“I started thinking that in order for environmental journalism to move into the new era of media, we needed to become a little bit more tech savvy,” Macleod told me in a recent call. “The use of data was very limited in environmental journalism – it didn’t really exist. It’s become more prevalent, more prolific in the past decade. But at that time, it was a niche, or a nice-to-have rather than a must-have in many media houses around the world.”

She set up the Oxpeckers Center for Investigative Environmental Journalism towards the latter half of 2012 as a nonprofit company. Oxpeckers investigations are carried out through its network of tech journalists, data wranglers, or traditional investigative reporters with different specialities, which are then applied to specific projects.

In addition to building big datasets and visualising them using interactive maps, Oxpeckers experiments with tools like drone photojournalism, soundclips and visual storytelling to maximise impact.

“More and more media are now mainstreaming the kind of work we do.”

Its work sometimes overlaps with and informs the work of environmental campaigners – tip-offs are welcome via the website, and there is a section dedicated to actions interested individuals can take – but Macleod is clear about Oxpeckers’ mandate. “I always say we’re a media company, a media production company. We’re not activists – we leave that up the to experts,” she said.

And what’s the significance of the name, Oxpeckers? Writing in a chapter in The Routledge Handbook of Environmental Journalism (2020), Macleod explains that oxpeckers are “small brown birds with yellow and red bills that serve a useful function in the African savannahs by removing parasites from wildlife. They are the mascots of our small unit headquartered in South Africa because, like them, we peck away at parasites and remove them from the environment one by one.”

Data as an untapped resource

Oxpeckers’ close work with complex datasets seems particularly important in parts of the world where public access to information is a luxury, not a right. For instance, South African court data is cumbersome to gather, but Oxpeckers wanted to create a map where people could follow the latest court cases on rhino poaching in the country. So in 2014, they did just that.

Oxpeckers also has a tool, #WildEye, for tracking environmental crime in different regions of the world. After implementing an easy feedback tool on the #WildEye platform, Macleod has heard from dozens of other organisations around the world explaining how useful the tool has been to them.

One example is Warren Sweeney, Chief Analysis Officer for Africa at Freeland Africa, who is part of the Big Cats Working Group. He told me that they made use of #WildEye in 2021 to gain a greater understanding of the illegal line bone trade in Mozambique, Tanzania and South Africa.

Oxpeckers makes all of its datasets open-source, with a strong commitment to transparency and sharing. “The tools we put together are about liberating data for use by organisations that would like to use them for their own purposes,” Macleod explained. “We’re a little bit different from other organisations, in that those who work with data will tend to find datasets from another organisation, and then reuse it. We actually build unique datasets for various reasons, including using the data for investigative journalism.”

Long investigations, committed teams

Something that really sets Oxpeckers apart is the length of their investigations in sometimes high-risk environments, and their commitment to following up on a story even after it has been published.

“We did some excellent work using our #MineAlert tool, where we did an 18-month-to-two-year investigation into what gets called ‘orphan mines’, or what we call abandoned mines,” Macleod told me. “We did a deep dive into data on mines throughout South Africa, that have been abandoned for various reasons, including the fact that they’re no longer profitable.

“Then we looked at the environmental footprint of those mines. What happens when these mines are abandoned, and not rehabilitated? And that has ended up in the change of policies, laws and practicalities around orphan mines. That’s one of the projects we’re very proud of, and it’s won awards.”

Another example is the 2015 Oxpeckers investigation into the upsurge of black rhino poaching in Namibia, which took the best part of a year to put together. The investigation won its writer, John Grobler, and Macleod, as his editor, the prestigious CNN/Multichoice Environment Award.

Commenting on the panel’s decision, chairperson Ferial Haffajee specifically highlighted the length of time Oxpeckers had put in to carrying out this often slow, tedious work: “The team did this [investigation] for 10 months. That’s a very long time in the era of the tweet and the parachute in-and-out journalism. […] It shows real commitment to a very complex story that takes you from Nanjing province in China all the way to the deserts of Namibia.”

“The use of data was very limited in environmental journalism – it didn’t really exist.”

A pioneer in environmental journalism

A lot has changed in approaches to reader revenue since Oxpeckers’ founding, but its nonprofit funding model has protected it somewhat from an overreliance on advertising or the whims of big tech. Just under 90 per cent of Oxpeckers’ funding comes from donors and sponsors of projects, and the other 10 per cent is from collaborations with other media partners.

“This funding model works for us,” said Macleod. “It’s less admin-heavy than going behind paywalls, etc. Then we would have to set up a whole different structure. So hopefully it will continue.”

From Norway to Hawai’i, what actually gets reported by media companies (and how) has changed a lot, too – endorsing Macleod’s hunch from back in 2012. All aspects of environmental journalism, whether climate modelling, environmental justice or extinctions, are now much more common. There is public demand for content that visualises the crisis in interesting and accessible ways, too.

“More and more media are now mainstreaming the kind of work we do,” Macleod explained. One of the things she is most proud of is Oxpeckers’ influence in this realm: “The fact is, environmental journalism has become sexy. We can’t claim all the credit for that. But I think that we’ve probably been playing a big role in making it a topic that’s a must-have.”

Oxpeckers also gets more and more frequent requests from organisations who want to do environmental reporting, but lack the expertise. “From that has sprung some great collaborations,” said Macleod. Examples include work in East Africa, Europe and Asia with the Earth Journalism Network, and on snow leopards in Asia and story grants in Africa with the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organised Crime (GITOC).

Training the investigative journalists of the future

The second thing Macleod is most proud of is Oxpeckers’ mentorship of young environmental reporters through their fellowship programme. “There’s a number of young journalists who have been part of our reporting on the environment, and that was my mission, my inspiration, originally. So it’s sort of a legacy project. These are mostly women journalists who are operating in the sector.”

Who are the kinds of people who are attracted to the fellowship programme? “Journalists interested in cross-border collaborations, those digging into financial issues. Then there are the data journalists, the techies – we’re seeing people from more and more disciplines getting involved in environmental journalism,” said Macleod.

Looking ahead, she hopes that this mentorship will continue and the legacy of Oxpeckers will be embodied in its persistence – pecking away, one parasite at a time.