Diversify funding to fuel your future

But apart from transforming the existing thinking and models discussed in the three pillars of a successful monetisation strategy, there are other areas in which publishers need to make strategic changes beyond the traditional norms of publishing and distribution – one being funding source diversification.

What goes around comes around

Funding has been receiving a lot of attention these days as publishers look to governments, non-profits, public and commercial interests to help keep the keyboards clicking in the newsrooms. But subsidising journalism isn’t new; many programmes originated in the 18th century and continue today. Here are a few examples…

Government-funded

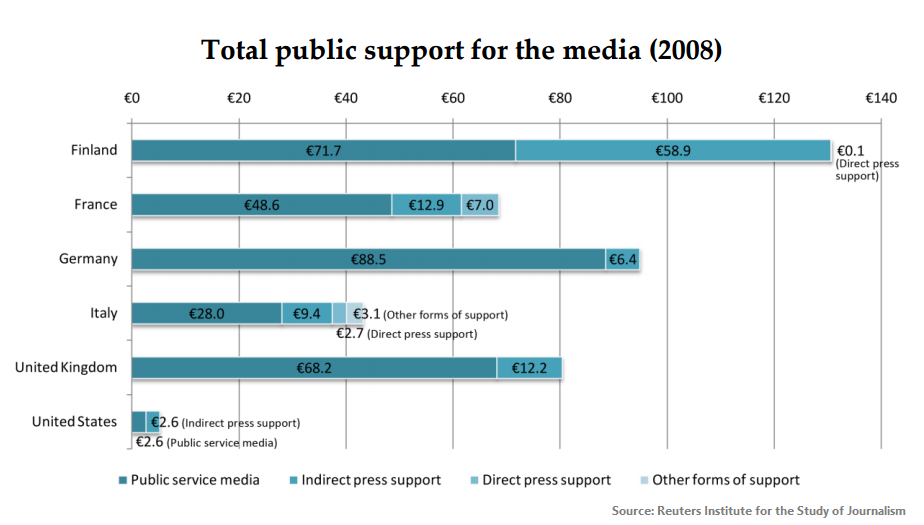

According to Reuters, government support for media, particularly in Europe, is greater and more widespread than most people think. Print publishers receive large, and often overlooked, indirect support in the form of postal subsidies and VAT exemptions or reductions.

Unfortunately, that support remains heavily weighted in favour of legacy organisations and industry incumbents.

In the US, postal rate subsidies go back as far as 1792 when the Post Office Department was created in a post-revolutionary America. In 1970, government support for newspapers and magazines reached US$4 billion.

In Canada, print magazines, non-daily newspapers and digital periodicals can apply to receive annual grants from the Canada Periodical Fund. Use of funds can vary from creation of content, through to marketing and distribution, but there are rules of engagement and use that must be followed. To ensure the integrity of the programme, the government-funded agency performs audits on randomly chosen recipients every year.

Canadian magazines and newspapers receive provincial sales tax relief on printed editions, but not on their digital counterparts. This is similar to most of the European Union where member states can apply for reduced VAT rates on printed newspapers and periodicals, but not on electronic editions. Needless to say, this exclusion of digital products has resulted in a significant amount of lobbying from the Professional Publishers Association (PPA), the European Magazine Media Association (EMMA) and others for over a decade.

Headway was finally made this year with the European Commission agreeing to reduce VAT rates on digital magazines, newspapers and books. No such plans are in place in the US or Canada for similar subsidies, but there have been urgent pleas by Canada’s largest publisher for more direct government support for traditional media – something most Canadians consider an essential service and imperative in a democratic society, but still fear that government funding may lead to expectations that what they pay for, they should own.

Public-sector funded

British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is the poster child for public-sector funded journalism through a mandatory licence fee. But it also has a commercial arm – BBC Worldwide – a wholly-owned subsidiary of the BBC that includes a number of brands and products, including magazines published through Immediate Media, such as BBC Good Food and BBC Top Gear.

As a government-owned entity, it’s no surprise that the BBC has been criticised for decades for its alleged political and social leanings. More recently its focus on growing BBC Online has created an uproar with commercial publishers who say that it is overstepping its bounds by expanding into local media and blurring the lines between its public service and commercial interests.

Crowdfunded

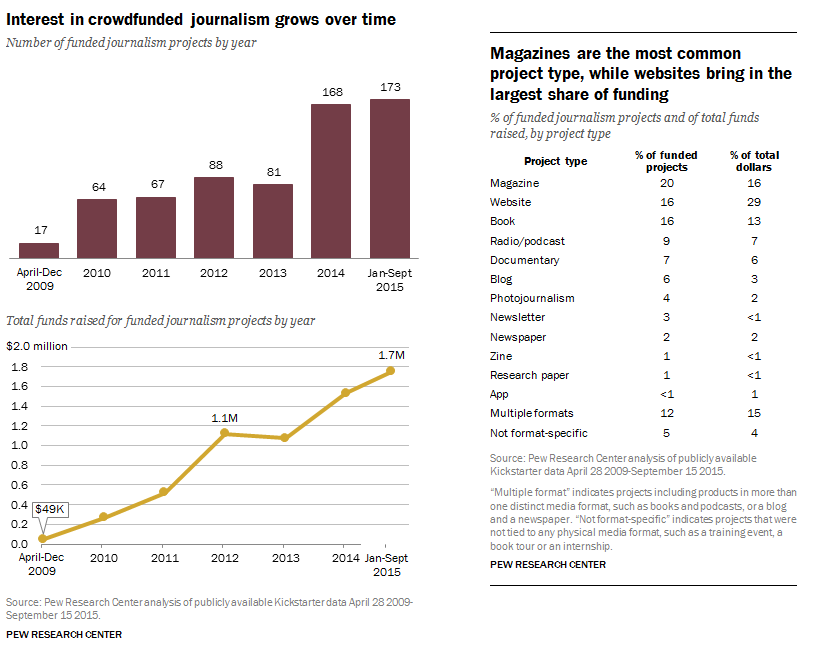

Although crowdfunding of journalism is just a drop in the bucket compared to other financial sources, its popularity is growing with media organisations, producing roughly a quarter of journalism projects on Kickstarter with magazines leading the way.

But Kickstarter isn’t the only source of crowdfunding for journalism. De Correspondent, Krautreporter, and El Español together received more than US$1m over a three-year period working outside of world’s largest funding platform.

Non-profit funded

When one thinks about non-profit journalism, some organisations immediately come to mind, including Huffington Post, ProPublica and the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists which backed the much heralded Panama Papers investigation.

Non-profits’ role in journalism continues to grow, but with it come concerns over the lack of guidelines around ethical issues including transparency, disclosures, journalistic firewalls and dark money.

Excluding a couple of exceptions such as The Guardian (operates under a public trust) and Tampa Bay Times (a taxable subsidiary of the Poynter Institute), it’s not often we see traditional media operate under a non-profit structure. But with declining circulation, plummeting ad revenues and willingness to pay for news trending downward, non-profit business models are becoming more popular with established brands.

Early this year the Philadelphia Inquirer, the Philadelphia Daily News and Philly.com were donated to The Philadelphia Foundation and housed under a new non-profit – the Institute for Journalism in New Media. It remains to be seen if this new move by the Philadelphia Media Network will result in returns those before them were unable to realise.

Poynter didn’t see success when the highly profitable Tampa newspaper donated shares to fund Poynter’s operations in 1978; it lost millions of dollars in 2013 and 2014. The Guardian has also been bleeding ink and is now forced to cut expenses by 20% over the next three years.

Despite these failures, non-profit funding should not be fingered as the founder of misfortune. Success depends on the ability to manage the flow of cash in and out of a business – something many for-profit publishers still haven’t figured out how to do in this digital age.

Non-government funded

In October 2015, European publishers’ favourite frenemy, Google, launched its Digital News Initiative Innovation Fund to “spark new thinking” in digital news media. The technology behemoth allocated €150m over three years in the form of a “no-strings-attached” funding programme for publishers.

I can’t help but find this rather ironic given the very rocky and often litigious relationship so many publishers, both individually and at the national level, have had with the biggest source of traffic to their websites – traffic that drove both subscription and ad revenue.

Instead of sitting down at the same table and talking about how to foster a win-win relationship, publishers literally ignored the benefits Google had to offer, choosing instead to go to war with the titan of tech, even at the expense of their own revenues and traffic. Let’s be honest; this new “peace offering” is just a modern form of extortion, but Google is happy to pay it in order to calm the stormy seas. It’s no surprise that publishers didn’t think twice before flocking to take advantage of Google’s good graces; as of February 2016, 128 of them were approved.

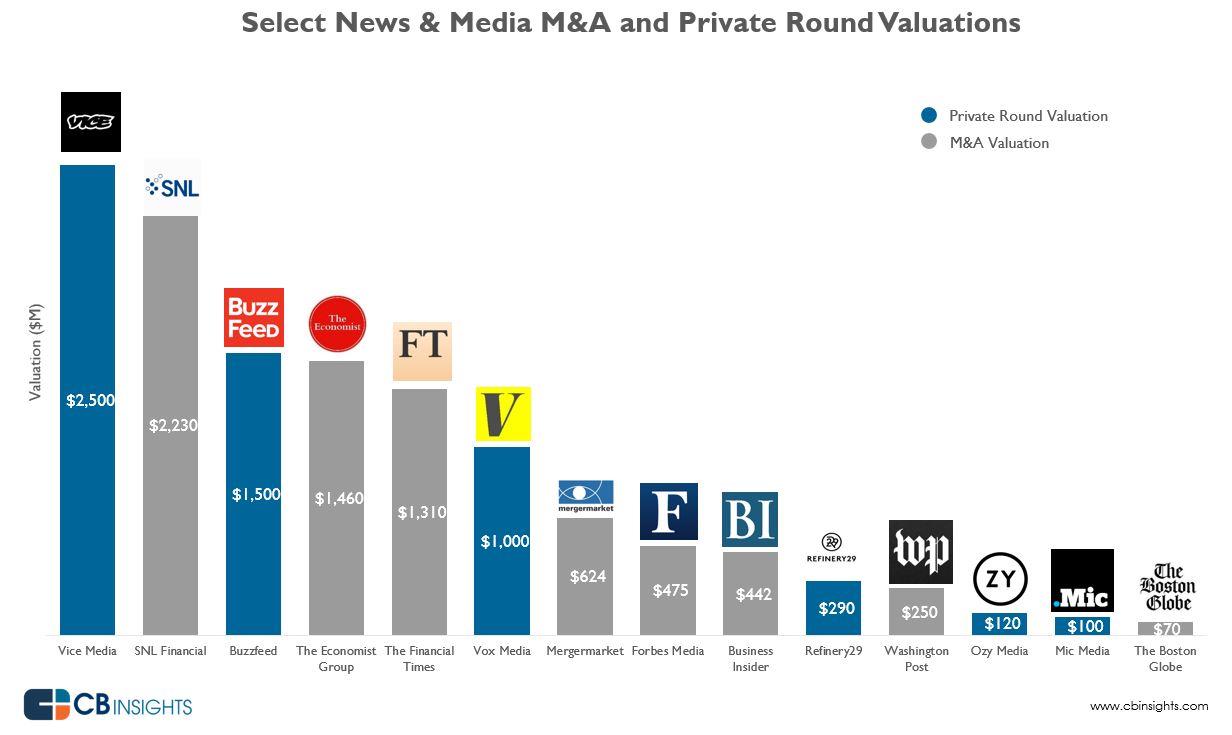

Another interesting turn of events over the past decade is the interest bullish venture capitalists have shown in media investments, seeing content (not necessarily magazines and newspapers) as a growth business. From Vice to BuzzFeed to Refinery29, hundreds of millions of dollars have been injected into digital media that targets a new generation of readers.

In the US, 1,000+ foundations awarded over 12,000 media-related grants totalling US$1.86bn over a three-year period ─ 28 per cent of which were focused on journalism, news, and information. Since then the philanthropy gravy train has continued to pick up speed with foundations and individual donors investing billions of dollars in journalism and media. But as in all things that look too good to be true, some donations come with baggage that can take the shine off the purse that is pulling media’s strings. Buyer beware!

Public funded

This isn’t something we see much in the magazine and newspaper industries, but it does work extremely well in Public Broadcast Systems (PBS) and National Public Radio (NPR). Although these organisations accept contributions from corporations, foundations, non-profits, universities and governments, their primary funding comes from consumers. This not only makes them accountable to their audiences, it also gives viewers and listeners a sense of ownership and commitment and encourages public participation in programming.

While some publishers like The Guardian look to fund journalism through membership programmes that include exclusive events, discounts and gifts, PBS in the US has added fundraising to the mix which builds a sense of responsibility with members, leading them to believe they are contributing to a good cause. It creates community and dialogue between PBS and their audiences as opposed to the walled monologue garden many traditional publishers offer their readers.

Internal subsidies

It may not seem obvious, but circulation has been an internal subsidisation model for publishing for years. Invented decades ago to bring transparency between publishers and advertisers, let’s be honest, circulation ended up driving publishers to print more copies than would ever get read in order to inflate advertising rates. Circulation revenues could never cover the costs of producing, printing and distributing content, so instead they were used to fuel advertising pricing based on total numbers. Circulation became publishing’s magic little pill.

In light of massive digital content consumption, these circulation models have to change. But, I’ll save that constructive rant for another article.

So what should publishers do?

Obviously based on the above list, which is in no way complete, there are many different sources of funding available to media. And although government subsidies seem to be high on everyone’s wish list and should not be dismissed, government should never be the primary source of revenue for publishers. They should not seek it as the primary source, or even as a majority source. Instead, publishers need to look beyond government handouts and start having a hand in raising money for themselves beyond subscriptions, advertising and memberships.

Some may submit that if you’re open to alternative forms of funding, you will be expected to produce content that is guided by those third parties. They’ll suggest that your editorial integrity will be put at risk by accepting their money. I disagree. If you have diversified funding from several sources (the more non-partisan the better), no one source will be able to interfere with your journalistic integrity.

For hundreds of years, publishers have relied on readers and advertisers to fund their business. It worked in print, but digital created a perfect storm which defined new rules of engagement where:

- The free flow of content quickly led to its commoditisation

- Advertising space scarcity which powered print revenues was supplanted by unlimited, low-priced digital inventory

- Changes to consumer behaviours in terms of how they discover, consume, share and monetise (or not) editorial and advertising content was contrary to everything publishers came to expect from readers

Digital has created a whole new ballgame that requires thinking and playing outside the printer’s box…

1. Be open to alternative funding resources

Identify which funding sources are more appropriate for your content and create a business plan for each source which clearly states the ROI for the funder and their role in your success.

2. Protect your editorial integrity at all costs

Choose funding sources that align with your business goals; walk away from those that don’t. And maximise the number of funding sources so you can minimise any threat to your journalistic integrity.

3. Be accountable

Think of yourself as a publicly-listed company with your audience as shareholders – shareholders to whom you must be accountable. After all, readers fund the expansion of your business and your day-to-day operations. Even non-subscribing readers are effectively shareholders; their attention to your editorial and advertising content costs them in mobile data charges and ends up generating advertising revenue for you. You have a fiduciary responsibility to all your funding sources which includes your readers and your advertisers.

One of the world’s most influential and iconoclastic business thinkers, Gary Hamel once said, “Large organisations don’t worship shareholders or customers, they worship the past. If it were otherwise, it wouldn’t take a crisis to set a company on a new path.”

Publishing has been in a crisis since 2000. It’s time for us to carve new paths to profits by diversifying not only our business, but our funding sources as well.

More like this

What publishers must know about content aggregation in 2016

Mastering the three pillars of a successful monetisation strategy