Can platforms ever be trusted in an ‘attention economy’?

Trust has had its fair share of attention during the last couple of weeks.

Without giving Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg too much credit, he did kick off the debate; claiming his disciples will – in future – decide if publishers on his social network’s News Feed are trustworthy, as analysed by FIPP last week.

On cue, the Edelman Trust Barometer 2018 was published, casting long shadows over the trustworthiness of platforms. But arguably the most significant event, relating to both trust and platforms, happened in Davos during the World Economic Forum’s annual meeting of great minds. Here media and technology bigwigs sat down to debate whether technology can be trusted when platforms are out to monetise and monopolise (our) attention.

Social media, argued The Economist in November last year in a leader article, can be a threat to liberal democracy. The reason? Social media wields extraordinary influence. They make money by putting photos, personal posts, news stories and advertising in front of you. And because they can measure how you react, they know how to get – deeper – under your skin, or in your mind. During the entire process they collect data to fine tune their algorithms to even better arrest your attention in what has become an “attention economy”.

But there are problems. Facebook admitted that between January 2015 and August last year, 126 million users may have seen Russian misinformation while scrolling on their platform. Google acknowledged to hosting 1,108 Russian-linked videos on Youtube, while Twitter fested up to 50,258 automated (read: ‘fake’) accounts connected to the Russian government, which tweeted more than a million times. These figure are only the fake accounts and activities linked to the US election. Research from the University of Southern California and Indiana University published in March last year suggests that in general up to 15 per cent of all Twitter accounts are not managed by real people at all but by bots.

In who do we trust?

Fake accounts spreading false information (fake news) does not enlighten politics, society or the fundamentals of liberal democracy. It does exactly the opposite. It might come as little surprise then that ‘fake news’ has hurt the reputation of social media sources. In its global ‘Trust in News’ survey published in October last

year, research firm Kantar found that there has been a ‘reputational fallout’ in 2017 focused on social media companies while the reputation of ‘traditional media companies’ have been more resilient.

The study, which surveyed 8,000 individuals across Brazil, France, the United Kingdom, and the US about their attitudes to news coverage of politics and elections, found – among others – that:

- The reputational impact of the ‘fake news’ campaign has been predominantly borne by online

only news channels, social media platforms and messaging apps; - News coverage of politics and elections on social media platforms (of which Facebook was dominant

with 84 per cent usage) and messaging apps (of which Whatsapp was the most used) were trusted less by almost 60 percent of news audiences (58 per cent and 57 per cent respectively); and - ‘Online only’ news outlets also sustained significant reputational damage in this respect:

‘trusted less’ by 41 per cent of news audiences.

The fall of trust in social and search platforms and of the credibility of peer communication, has largely contributed to the overall decline of trust in media worldwide, as confirmed by the findings of the 2018 Edelman Trust Barometer, which was published last week. The annual trust barometer found that the media is now the least trusted institution (the other institutions surveyed are NGOs, business and government), distrusted in 22 of the 28 participating countries with an average ‘trust score’ of 43 per cent. However, participants defined ‘media’ as both content publishers and technology platforms. While trust in platforms showed a decline (-2), trust in (traditional) journalism increased (+5). See this chart.

In fact, trust in platforms decreased in 21 of the 28 countries where the barometer found that 65 per cent of people receive news through platforms such as social media feeds, search or news apps. 62 per cent of respondents admitted that they did not know how to distinguish good journalism from fake news.

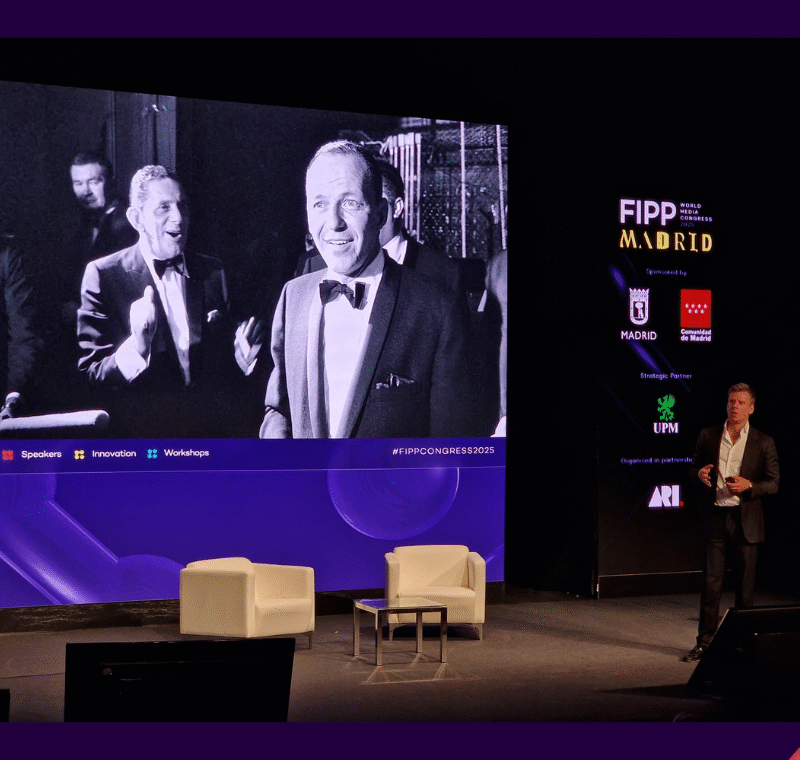

This inability to distinguish between truth and fiction was further dissected during a panel discussion ‘In technology we trust?’ during the recent World Economic Forum gathering in Davos. Panellist Rachel Botsman, author of ‘Who can you trust?’ and lecturer at the Said Business School, University of Oxford, said people need time to establish trust but technology accelerates processes and trumps trust. “We live in an era where we trust speed… But trust needs friction, trust needs us to slow down. The problem we have is that technology wants to automate this process.” It leaves less time for people to decide if they trust the person driving the Uber, or the content placed in front of them.

Then when things go wrong, the question arises: who is accountable? asked Botsman. Would it be the platform or the individual (who posted the content)? According to her platforms were not only allowed to, but also extracted massive value, from matching supply with demand. “But you cannot extract all the value and not take responsibility for what happens on your platform. You can’t have it both ways.”

We need to sort out individual vs company responsibility. It’s too easy for platforms to say the trust resides between users. pic.twitter.com/Z4qwzIjfCU

— rachel botsman (@rachelbotsman) January 23, 2018

Tech: the new tobacco?

Fellow panelist, Marc R. Benioff, chairman and chief executive officer of Salesforce.com, agreed. He said it is the responsibility of tech company chief executives to focus on trust. “In the world of connected products and the fourth industrial revolution, trust needs to be the highest value in your company. If growth is more important than trust, something is wrong. Convenience should never trump trust.”

He argued that the opposite is happening. Because the CEOs of the tech giants are not taking responsibility for trust, signals are pointing to the inevitability of regulation. “Some of the technology is so powerful and sophisticated, so deep and multidimensional that not even the companies themselves understand how it is being used.” That’s why, Benioff argues, regulators need to pay more attention.

He goes as far as likening it to the cigarette industry of old or the banking industry before the financial crisis, when regulators did not do enough. “This is when we need governments and regulators to point to the true north,” he said.

Benioff said that after he has worked around his room of executives he then quizzes his AI assistant. “I ask Einstein, ‘I heard what everybody said but what do you actually think?'” https://t.co/4bD65Z98My

— Marc Benioff (@Benioff) January 25, 2018

But Botsman warned that regulators are in all probability ill equipped to the task. She said trust shifted from traditional institutions to individuals. “Where trust used to flow in a top down hierarchical fashion… there is now a distributed form of trust that flows sideways directly to individuals like strangers, peers or colleagues.

This is a real challenge for regulators because a lot of regulations are designed for traditional institutions to function within a top-down, hierarchical way. “How do you regulate a platform. How do you break up these network monopolies? The way regulators naturally think is: ‘where is the centre, where it the centre of accountability?’ and that’s a real problem when you have billions of users who are essentially the product.”

She said a perfect example of this is when Zuckerberg called on users to rate the trustworthiness of content. “We have to ask ourselves; do we want Facebook (users) to be arbiters of truth?”

Sir Martin Sorrell, chief executive officer of WPP, said the fundamental issue remains that tech companies should admit they are publishers and be treated as such. He said companies like Facebook and Google need to acknowledge, which they have not done to date, that they are in fact media companies because they are starting to hire staff to monitor editorial content on their platforms. By doing this they admit to asking the fundamental question: Can we trust the content on our platforms? “They need to acknowledge the fact that they are media owners”.

More like this

What does Facebook’s algorithm change mean for publishers?

Do publishers and platforms really need one another?

When Facebook fell out of love with news