The Mr. Magazine™ Interview: “I like to feel that our readers aren’t a mailing list,” says William R. Hearst III

“We look at the advertising as the person who creates that product telling the story of their product. And if we believe that their product is good and their story is honest or amusing, then we induce them to advertise. In the long run, I think we’re going to make it or not make it on whether readers think we’re doing a good job and are willing to pay something. And if you look at the balance sheets of magazines and newspapers, what you’ll see is more revenue is coming from circulation, sometimes online circulation, sometimes print, and less revenue is coming from traditional advertising.” Will Hearst

“Publishing magazines, to use a mathematical analogy; it’s an infinite, dimensional space. It’s not like there’s five niches and you have to pick one. There’s always something else; it’s always around the corner that there’s some originality. I believe in Michael Porter’s theory: Don’t compete to be the best at something that exists, compete to be different. Compete to find something that no one is doing and then do that better than anyone else does.”

A Mr. Magazine™ launch story…

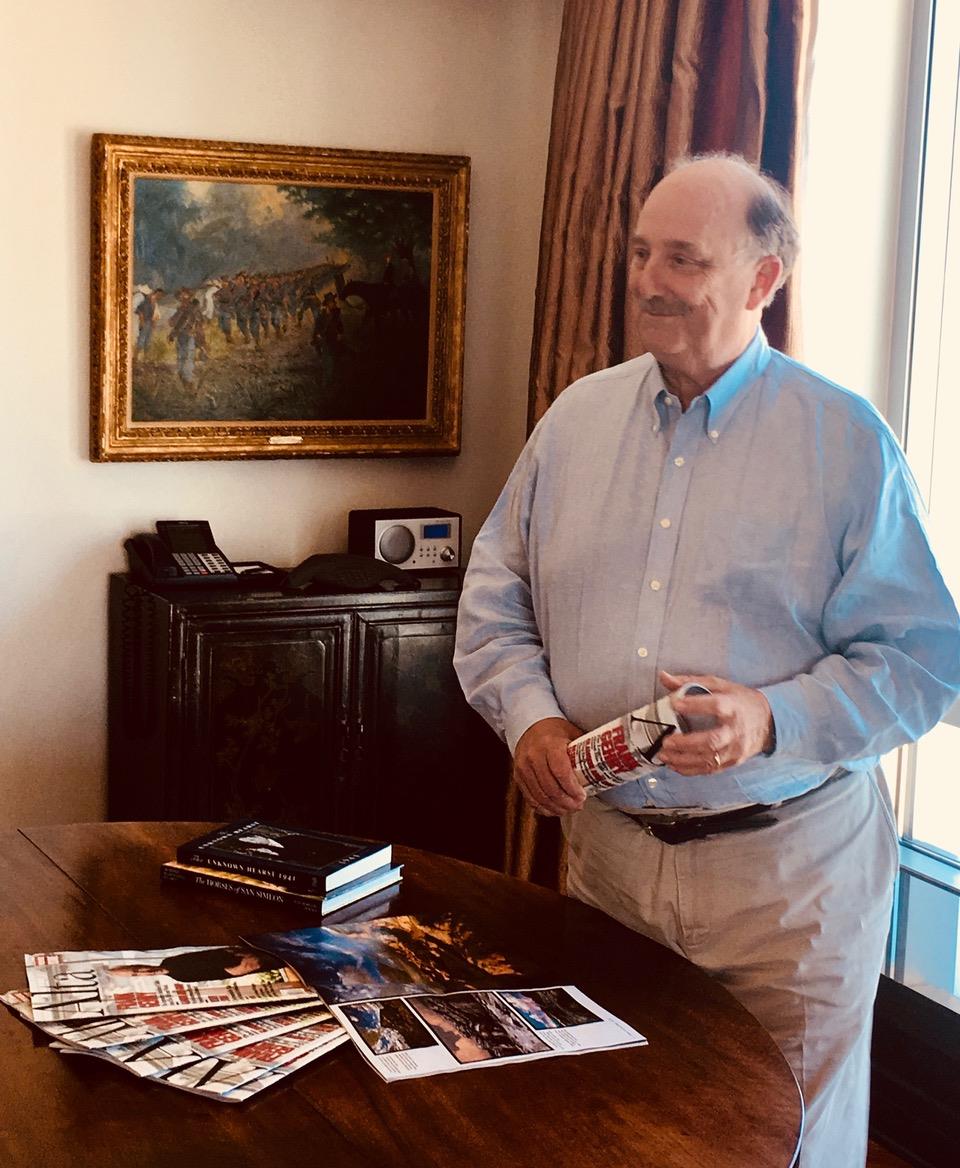

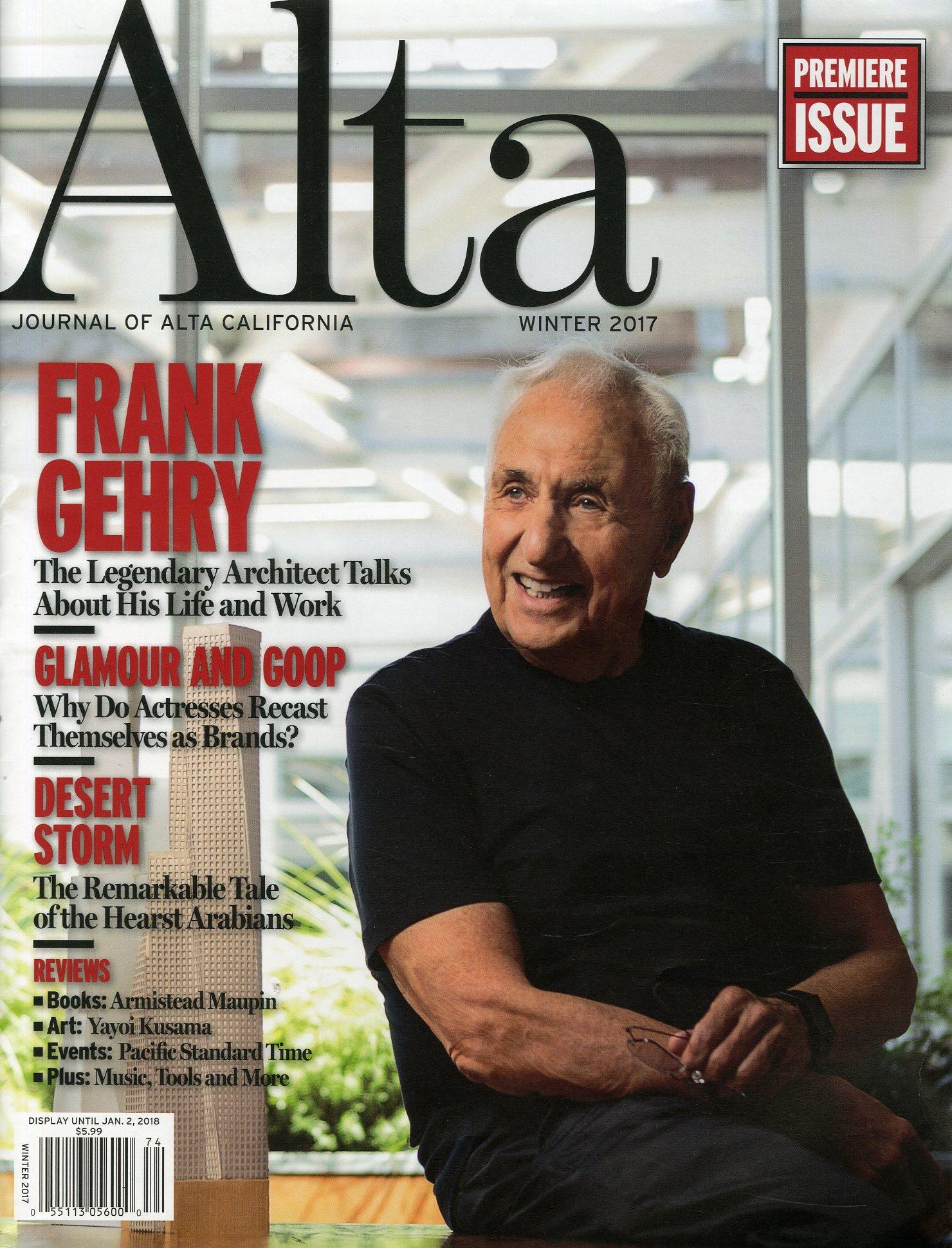

William R. Hearst III (Will Hearst) is certainly no stranger to the world of publishing. From newspapers to magazines, he has ran the gamut of creating and guiding content for most of his life. Publishing to him, magazines in particular, is like facing an infinite, dimensional space, with the possibility of originality around every corner. Today, that originality comes in the form of a beautifully-done, large format title called “Alta Journal of Alta California.”

|

I spoke with Will recently and was fascinated by many of his ideas and suggestions when it came to business models, advertising, and the fact that he believes in Harvard’s Michael Porter’s theory that one shouldn’t compete to be the best at something that already exists, but instead, one should strive to compete to be different. Compete to find something that no one is doing and then do that better than anyone else does. Enter Alta. The magazine is dedicated to speaking to the local communities of the area that Will felt wasn’t being included in any conversation that already existed. So, being uniquely different was organic for the brand.

He is a firm believer in print, yet has a definitive desire to serve the online reader as well, and definitely represents the Print Proud Digital Smart model excellently. His staff gets full credit from him when it comes to editorial talent and factuality. In fact, he also follows mathematician, Don Knuth’s lead when it comes to monetarily rewarding readers for pointing out typos and factual errors in the editorial of the magazine. He has a penchant for exactness that in this age of “fake news” and “alternative facts” is greatly appreciated.

So, I hope that you enjoy this Mr. Magazine™ interview with a man whose greatest wish for his new publication is that he can make the experience of reading the magazine a little bit like the experience of actually living it, William R. Hearst III, editor and publisher, Alta Journal of Alta California.

But first the sound-bites

On his idea of the new media model for Alta: My notion of the old media model is, and you can exaggerate here; the extreme of the old model is that you’re going to have a genius editor, William Shawn, or maybe you have Helen Gurley Brown, or somebody who is able to answer every question. And then the staff basically runs around executing that plan. At the opposite end of the spectrum, you have a complete, sort of blog community, every opinion is equal; you’re not really talking about facts; you have a comment section of the average website. And I thought there should be something in the middle where you had people who really wanted to work at being editors. I like to feel that our readers aren’t a mailing list, that it’s an actual community. And the community could disagree with us; the culture could change and we would need to change with it. So, I thought of a more dynamic, open model; a little more democratic, but not 100 per cent democratic either.

On his challenge to readers that if a factual mistake or misstatement is found in the printed magazine, they will receive $10: I stole the idea from Don Knuth who wrote the print bible of software. He was writing technical articles where mistakes and typos meant that the software didn’t work or what was stated was wrong, but I just felt like we should challenge ourselves. And I worked for a guy when I was younger, the editor of the editorial page of The San Francisco Examiner, and his view was that there should be no typos on the editorial pages. There could be typos in the newspaper because you’re on deadline and you’re in a hurry, but in the things where you were really putting the brand of the owner on the page, there should be no typos.

On why he insisted on a print component for Alta: There are two reasons really and one of them is a content reason and one of them is a business reason. The content reason is that I wanted to deal with things that last a little bit longer. I was thinking about the people that I know: writers, photographers, editors; these are people who often write books, that take some time to write something. I was less interested in immediacy; I wanted things that had a lasting quality. And one reason print attracted me was I wouldn’t be yoked to the daily cycle of doing a website or a blog, because if you’re doing the Huffington Post or you’re doing these sites that have to be updated every 24 hours, you’re kind of forced to follow the news.

On whether he foresees a day without a print version: I don’t really. It’s like asking whether you think books will go away because there are books on Kindle? There’s a pace to writing a book. It just isn’t instant; it requires research, commitment, and digging deeper into a subject. And that’s the area in which I like to work, so I think that will persist. Maybe paper will go away, but I don’t think books will go away, and therefore I don’t think magazines and publishing will go away.

On what he would hope to say that he had accomplished with the brand one year from now: In your interviews, I was very struck by the guys from Garden & Gun magazine. This isn’t my demographic, but these guys really know what they’re doing. They know what kind of article fits in their magazine and what kind of article doesn’t. And they might have an article about hunting dogs that we would ever run, but for them it’s just right. They know their audience. And they’re regional, but they have the culture of their region in their blood. And that’s the kind of magazine that I’d like to be. I’d like to be favourably compared to those guys, in terms of writing quality and topical interest. If you live in that area; if you’re in my audience and in my community, I’d like you to feel this is your magazine. That’s what I’d like to say in a year.

|

On whether the editorial board and the inspirations that are credited in the magazine are his, Will Hearst’s, or Alta’s: They belong to the Journal of Alta California and we sort of rounded up the input of our staff and even wrote to a few people who told us we didn’t have enough women or people of other ethnicities, so we reedited the Inspiration Board to be a more complete history of our region. And less just people that “Will” liked to read. And we have our Board of Contributors, some of whom are active contributors and some of whom are on standby, because there are special topics where they have expertise.

On the 1970s-1980s magazine that tried to be the New York of California called “The New West”: They did a very good job, but I think they were to some degree yoked to this shorter cycle. They were modeled on New York Magazine, which was weekly, then bimonthly. But they had to keep up with events. A new politician comes onto the scene and they had to write about it. And new restaurants open.

On being both the editor and the publisher: Well, that’s another compromise. My title was originally going to be “proprietor.” I wanted people to think of the staff as the editorially creative talent, and I was there as a financial investor and as the owner; as the buck-stops-here. But I didn’t want to pretend that I would be doing everything, because you can’t do it all. The business is made out of people; it’s not made out of numbers.

On advertising and how he wants it to work in Alta: I wanted to follow the equation the way I think it’s moving, where readers have to be served well enough that you can begin to extract more revenue from them. They’re not going to pay for something that’s no good and they’re not going to overpay relative to competition. But my feeling is that good media will become more paid, and you’ve seen The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal start to charge for their websites. Kindle books are not free because there’s advertising in them. I think there’s a countertrend where readers have to pay a little more and advertisers are willing to pay more. And we wanted to anticipate that.

On advertising becoming less important over reader circulation revenue: Advertisers are more fickle than readers. Readers decide what they like and what they’re willing to pay for. Advertisers move in herds. And the herd is moving to online and the herd is moving to Facebook, and there may be good reasons to do that, but I think chasing the herd from the back is not a good business strategy.

On anything he’d like to add: Publishing magazines, to use a mathematical analogy; it’s an infinite, dimensional space. It’s not like there’s five niches and you have to pick one. There’s always something else; it’s always around the corner that there’s some originality. I believe in Michael Porter’s theory: Don’t compete to be the best at something that exists, compete to be different. Compete to find something that no one is doing and then do that better than anyone else does.

On what he would have tattooed upon his brain that would be there forever and no one could ever forget about him: We always had a great place to work; we always had fun and we were challenged.

On what someone would find him doing if they showed up unexpectedly one evening at his home: During the day, it’s probably reading or looking at manuscripts or calling people to see if I can cajole them into working with me. And at the end of the day, it could be a little bit of reading or it could be my kids. And once in a while, I like to solve math problems for fun.

On what keeps him up at night: What keeps me up at night is trying to make the experience of reading the magazine a little bit like the experience of living out here in the zone of arts and culture, technology and exploration. I’d like to do a little more environmental writing in the next year. I’d like to connect to that part of our history.

And now the lightly edited transcript of the Mr. Magazine™ interview with William R. Hearst III, editor and publisher, Alta Journal of Alta California.

In your second editorial of the magazine, you write that you’re not a big believer in the old media model, but rather you’re trying to create a new model; a community where subscribers, staff, everybody is curating the information. Can you expand a little bit on your understanding of the new model for Alta, Journal of Alta California?

Like a lot of projects, this starts with an idea or sort of a notion. I didn’t wake up as a youngster thinking that I wanted to start a magazine someday. The notion was a certain uncovered coverage area of the West, and its arts and culture.

I like to read; I’m a voracious reader and I’m involved with a magazine company and a newspaper company. I’ve been a newspaper publisher, so I’m very comfortable with reading, but I just felt that there was this underserved community that had to do with experiences of people who live in the West. People who sort of see the world like that New Yorker cartoon, but from a different point of view. One where New York and Manhattan seem very faraway and the immediate foreground is the beach and surfing, the mountains and the environment, Hollywood and Silicon Valley; these are our local communities. And I felt that I wanted to do something to talk to those communities. Then the idea of a magazine came second.

My notion of the old media model is, and you can exaggerate here; the extreme of the old model is that you’re going to have a genius editor, William Shawn, or maybe you have Helen Gurley Brown, or somebody who is able to answer every question. And then the staff basically runs around executing that plan.

At the opposite end of the spectrum, you have a complete, sort of blog community, every opinion is equal; you’re not really talking about facts; you have a comment section of the average website. And I thought there should be something in the middle where you had people who really wanted to work at being editors. Who would cultivate writers; look at pictures and put packages together, but also where some of the people who were writers would become editors, and some of the people who were readers would become writers, and not just in “Letters to the Editor.” So, there would be a much more fluid boundary between who the official staff people were and who the reader people were; who were the contributors and who were the advertisers.

I like to feel that our readers aren’t a mailing list, that it’s an actual community. And the community could disagree with us; the culture could change and we would need to change with it. So, I thought of a more dynamic, open model; a little more democratic, but not 100 percent democratic either.

|

But you take this community one step further; this is probably one of the few times in my 40 years of following the magazine industry that I find an editor challenging readers, telling them that you will pay $10 if they find a mistake in the printed magazine.

I stole the idea from Don Knuth who wrote the print bible of software. He was writing technical articles where mistakes and typos meant that the software didn’t work or what was stated was wrong, but I just felt like we should challenge ourselves. And I worked for a guy when I was younger, the editor of the editorial page of The San Francisco Examiner, and his view was that there should be no typos on the editorial pages. There could be typos in the newspaper because you’re on deadline and you’re in a hurry, but in the things where you were really putting the brand of the owner on the page, there should be no typos. So, I grew up in a culture where typos were, while maybe you couldn’t eliminate them; they were costly. And if you made a typo you had to apologize; you had to correct it and admit your mistake.

So, I stole this idea from Don Knuth that we would pay when people told us that we had a fact wrong, a reference that was incorrect, or we had a date wrong. There could be other kinds of mistakes that are more subject to interpretation, but when there are straightforward, factual mistakes or misstatements, or even gross errors of omission, we would make ourselves pay a fine to our readers who had found those things and we would honestly acknowledge them and move on.

And…

You’re dying to ask how much it has cost us so far, right?

I was going to say that you’re either a very wealthy man or…

No, we’ve paid out less than $100, but more than $10 since we put the policy in place.

In this digital age, why did you insist on a print component for the Journal of Alta California?

Will Hearst: We get asked that question a lot and I think there are two reasons really and one of them is a content reason and one of them is a business reason. The content reason is that I wanted to deal with things that last a little bit longer. I was thinking about the people that I know: writers, photographers, editors; these are people who often write books, that take some time to write something. I was less interested in immediacy; I wanted things that had a lasting quality.

I remember when I was a newspaper editor and being surprised that more people go to museums than go to sporting events. More people attend cultural events than attend things that we consider to be pop culture. And so I thought there was a large audience of people who were interested in the arts and culture and technology and ideas, and that audience was really not interested in breaking news.

So, the people that I wanted to work with were working on a different schedule. And one reason print attracted me was I wouldn’t be yoked to the daily cycle of doing a website or a blog, because if you’re doing the Huffington Post or you’re doing these sites that have to be updated every 24 hours, you’re kind of forced to follow the news. Something happens and you have to react to it.

I wanted to break away from that and print seemed more natural to enforce that discipline on us and we would bore the crap out of people online if we only updated the site once a quarter or once a month, or once a week even was too slow. So, that was kind of the content reason. The things that we wanted to write about and the people that we wanted to work with were not naturally immediacy people, they were people who were more reflective.

And the second reason was just economics. If you’re trying to do a daily, you have to have a large staff and you have to have people constantly working on a short deadline. It was just too expensive to do that. So, for the topics that we wanted to cover, something that had a more leisurely pace was better-suited.

Now, I do feel, going back to the community idea, that we need to serve people who don’t want print or who want to access articles online or want to access an archive. So we’re trying to find ways to make the online archive and the online edition of the Journal of Alta California be very complete and no additional charge, where part of being a member is you get it all. You become a member and then you get everything.

And one of the things that I’m debating is whether we should put more things on the website. For example, we have a person who writes an article; he writes 2,000 words and we can run maybe 1,500. Well, maybe we should let the author go longer online for the people who really want to drill down one more level. So, we’re still trying to figure out what our online strategy is. We know what our print strategy is; we’re print people so we kind of know what to do and what we can afford to do.

Another question becomes: what should we do online? It shouldn’t be a scaled-down version of print. It should be an alternative extension of print. And we haven’t quite figured that out yet. I’m not anti-online. The 2018 online newspaper has probably 10 times more readers than the print newspaper, just to give you an example. So, I’m not turning my back on the online edition, I’m just trying to figure out how to make the two work together. But my core goal is more this membership idea; writing about certain topics; covering it well; and then serving that membership with whatever form of content is more convenient for them.

And as 10 years goes by and we have 100 readers for print and one million readers for online, then we should probably give up the print and be 100 percent online.

And do you ever foresee that happening in our lifetime?

I don’t really. It’s like asking whether you think books will go away because there are books on Kindle? There’s a pace to writing a book. It just isn’t instant; it requires research, commitment, and digging deeper into a subject. And that’s the area in which I like to work, so I think that will persist. Maybe paper will go away, but I don’t think books will go away, and therefore I don’t think magazines and publishing will go away.

I happen to like print; I happen to like the physical, tactile quality. You don’t need batteries; you can fold it up; you can tear it apart. But I tend to be a media consumer; I’m not a vegetarian when it comes to media. I’m kind of an omnivore. I like online; I like print; I like video; I like media.

It’s not unheard of for me that when I buy a book, I’ll buy the audio book and then buy the print book, and I’ll buy the Kindle book because I just really like that particular book. (Laughs) And I consume it different chunks at different times. It’s a little more expensive than maybe settling on one habit, but I think media consumption is about information and about human beings. It’s about learning; it’s not about print or online. It’s not about technology; it’s about the content of content.

That’s one thing I strive for in my teaching; to tell the students that I don’t want to teach them the toys of the profession, they keep changing. They need to learn the profession.

It’s very interesting; I give speeches sometimes to newspaper people and I find that if you’re a 60-year-old newspaper person, you’re kind of happy, because you’re going to retire and you can forget all about this technology. And if you’re a very young person interested in journalism, you’re very enthused about your career, because you’re probably going to be a blogger and appear on television, write, shoot your own pictures and maybe edit other people’s work. So, you have this multidimensional talent group in the younger generation.

And people in the middle are sort of lost, because they’re a little too old to learn all of the new skills; they’re a little more craft-union oriented, but they’re not close enough to retirement to turn their backs on it. They still have another 20 years to go.

The Hearst Foundation has a journalism award, and these are people who are freshmen in college, sometimes they’re a little bit father along, but they’re typically pre-professional, and they’re enthusiasm is amazing. And their skillset is so much wider than when I was a student. These people aren’t just photographers; they’re writers, photographers, broadcasters, bloggers, reporters, travelers; they’re multidimensional people. If you like media, you better be prepared to be a multitalented athlete. It’s a decathlon; it’s not a single-sport object.

|

Now that you have two issues under your belt; if we had this conversation a year from now again, what would you hope to tell me that you had accomplished in the year since Issue two was out?

I’d like to do more things outside of just California; I’d like to do the West. I think that’s really the topic zone. If I’m successful, I’d like to have people in Portland, Seattle, and San Diego. Maybe someone in Mexico; maybe some people in Denver who are correspondents and are sending us story ideas, and be where people in those geographies feel that we’re to talking to them.

In your interviews, I was very struck by the guys from Garden & Gun magazine. This isn’t my demographic, but these guys really know what they’re doing. They know what kind of article fits in their magazine and what kind of article doesn’t. And they might have an article about hunting dogs that we would ever run, but for them it’s just right. They know their audience. And they’re regional, but they have the culture of their region in their blood. And that’s the kind of magazine that I’d like to be. I’d like to be favorably compared to those guys, in terms of writing quality and topical interest. If you live in that area; if you’re in my audience and in my community, I’d like you to feel this is your magazine. That’s what I’d like to say in a year.

When I look at your editorial board and your inspirations; are these Will Hearst’s inspirations and editorial board or do these belong to Alta Journal of Alta California?

Will Hearst: They belong to the Journal of Alta California and we sort of rounded up the input of our staff and even wrote to a few people who told us we didn’t have enough women or people of other ethnicities, so we reedited the Inspiration Board to be a more complete history of our region. And less just people that “Will” liked to read. And we have our Board of Contributors, some of whom are active contributors and some of whom are on standby, because there are special topics where they have expertise.

But I like the idea of honoring the people who came before us, who were already part of the canon of Western literature. And Kevin Starr, who I wrote about in my editorial, was a big believer in the idea that there was a Western canon of writers, viewpoints and experiences. And that this was different than the East and that it was literature-defined; a little bit less academically and more from the life experiences of people who lived out here. So, I wanted to put that Board of Inspiration in to kind of show people that we were respectful of our elders and looking to take the next step, but also to be inspired by what they did before us.

In the late ‘70s or early ‘80s, I remember there was a magazine that tried to be the New York of California called “The New West.”

Yes.

In fact, there was two of them.

They did a very good job, but I think they were to some degree yoked to this shorter cycle. They were modeled on New York Magazine, which was weekly, then bimonthly. But they had to keep up with events. A new politician comes onto the scene and they had to write about it. And new restaurants open.

So, we wanted to step back from that kind of pace, which I don’t think works in the 2018 era. I think that’s very expensive to do. I don’t know how The New Yorker people can afford to be a weekly, because you have to have a permanent staff. And you have to have a large staff of writers who are employees, not just contributors. That’s a very expensive proposition. They have a great brand and they’ve been doing it for a long time and they have a very loyal audience, so I don’t think they’re in trouble. I don’t mean to suggest that. But for a startup that would be an impossibly ambitious idea, I think.

Being the editor and the publisher…

Well, that’s another compromise. My title was originally going to be “proprietor.” I wanted people to think of the staff as the editorially creative talent, and I was there as a financial investor and as the owner; as the buck-stops-here. But I didn’t want to pretend that I would be doing everything, because you can’t do it all. The business is made out of people; it’s not made out of numbers.

So, you have to get really good people and you have to give them a chance to shine. And to make their own decisions. Our editorial meetings are very, I want to say contentious; people are very candid about offering their opinions and we try and make decisions, and maybe my vote is the last vote, but I’m very interested in making sure that people feel like it’s their magazine, that it’s not the Will Hearst magazine; it’s a community magazine and I’m the proprietor. I’m the caretaker of the community, but I’m not the tsar. I’m not the president.

But as publisher, you have a say even about the ads. One of the things that captivated me when I was flipping through the pages was the type of advertisements that are in the magazine.

My study of publishing in this era is that little by little advertising is less and less important and more and more difficult to obtain. In the ‘70s and ‘80s when I was a younger person, advertising was 80 percent of the revenue. And circulation was something that you had to try and maximize, because you used it to support your advertising rate base. And I think little by little what has happened is that it’s become very expensive to keep giving magazines away, and you become a slave to advertising.

And I wanted to follow the equation the way I think it’s moving, where readers have to be served well enough that you can begin to extract more revenue from them. They’re not going to pay for something that’s no good and they’re not going to overpay relative to competition. But my feeling is that good media will become more paid, and you’ve seen The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal start to charge for their websites. Kindle books are not free because there’s advertising in them. I think there’s a countertrend where readers have to pay a little more and advertisers are willing to pay more. And we wanted to anticipate that.

I looked at the Whole Earth Catalog and other places where the advertising is really products that would be of interest to the readers as opposed to whomever is willing to pay the freight. So, we give very discounted packages for people who want to advertise with us and we’re very selective about advertising, because we’re not charging them very much and we can afford to be a little bit choosy. We don’t take ads from people whose products we don’t think our readers would be interested in.

We look at the advertising as the person who creates that product telling the story of their product. And if we believe that their product is good and their story is honest or amusing, then we induce them to advertise. In the long run, I think we’re going to make it or not make it on whether readers think we’re doing a good job and are willing to pay something.

And if you look at the balance sheets of magazines and newspapers, what you’ll see is more revenue is coming from circulation, sometimes online circulation, sometimes print, and less revenue is coming from traditional advertising.

But if you go back to the 19th century, when my grandfather was publishing in San Francisco, circulation was 80 percent and advertising was kind of like an extra. It was nice to have; it was an extra. But the real make-or-break was would people put a coin in the box to buy the newspaper? Or typically, buy it in single copy form. And I think, to some degree, we’ve come full circle.

|

Yes, in fact, one of the last new magazines that Meredith published, The Magnolia Journal, was based on 85 percent revenue from circulation and 15 percent from advertising, which is almost the opposite of the way things were.

Advertisers are more fickle than readers. Readers decide what they like and what they’re willing to pay for. Advertisers move in herds. And the herd is moving to online and the herd is moving to Facebook, and there may be good reasons to do that, but I think chasing the herd from the back is not a good business strategy.

Is there anything you’d like to add?

Publishing magazines, to use a mathematical analogy; it’s an infinite, dimensional space. It’s not like there’s five niches and you have to pick one. There’s always something else; it’s always around the corner that there’s some originality. I believe in Michael Porter’s theory: Don’t compete to be the best at something that exists, compete to be different. Compete to find something that no one is doing and then do that better than anyone else does.

If you could have one thing tattooed upon your brain that no one would ever forget about you, what would it be?

We always had a great place to work; we always had fun and we were challenged.

If I showed up unexpectedly at your home one evening after work, what would I find you doing? Having a glass of wine; reading a magazine; cooking; watching TV; or something else?

During the day, it’s probably reading or looking at manuscripts or calling people to see if I can cajole them into working with me. And at the end of the day, it could be a little bit of reading or it could be my kids. And once in a while, I like to solve math problems for fun.

My typical last question; what keeps you up at night?

Will Hearst: What keeps me up at night is trying to make the experience of reading the magazine a little bit like the experience of living out here in the zone of arts and culture, technology and exploration. I’d like to do a little more environmental writing in the next year. I’d like to connect to that part of our history.

And the other thing that keeps me up is who are the writers; who are the editors; who are the photographers, and where are the young writers? I think I have a pretty good Rolodex of people my generation who are proven writers, write on deadline, and who are good reporters, but we will have failed if we don’t find two or three young voices that no one has ever heard of. And I hope that we give them their first chance to be in the big-time. I hope that we discover them earlier and we promote them properly. And when they become so famous that we can’t afford them anymore; we will wish them good luck.

Thank you.

More like this

The Mr. Magazine™ Interview: Print is never going to go away, says Hearst’s Joanna Coles

The Mr. Magazine™ Interview: Content is about earning people’s attention