How and why politics, social issues and the F word have taken centre stage in mainstream women’s publishing

At the same time they have had to contend with the emergence of a new breed of women’s online titles engaging with their audiences in new ways, from Popsugar and Refinery29, which largely focus on style and health to The Pool and Broadly (from Vice) which major on social issues and are not afraid to take a stance on controversial topics.

Some brands have also had to deal with a backlash to the type of content they provided in previous years with critics arguing that their narrow perceptions of ‘beauty’ were causing a rise in eating disorders and different forms of body dysmorphia among young women.

Finding a voice in a changing era is marked by international female empowerment campaigns such as #MeToo and has become a priority. Mainstream fashion magazines though have quickly caught on to demand, and began publishing content that would engage readers in the same ways as their new digital competitors.

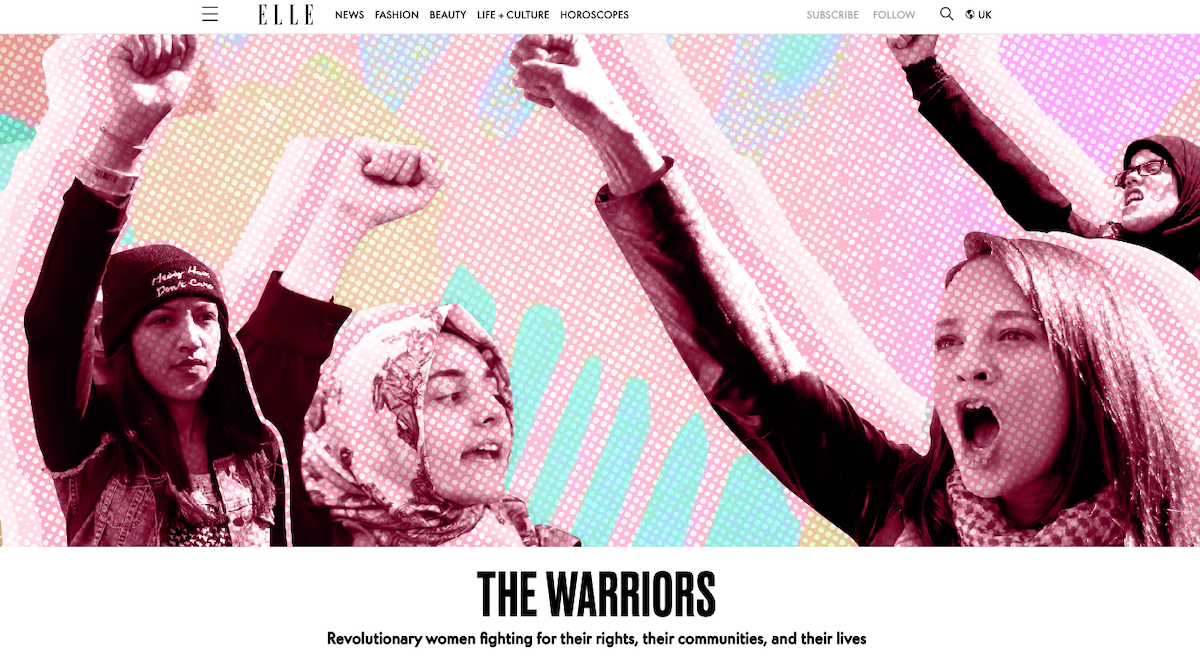

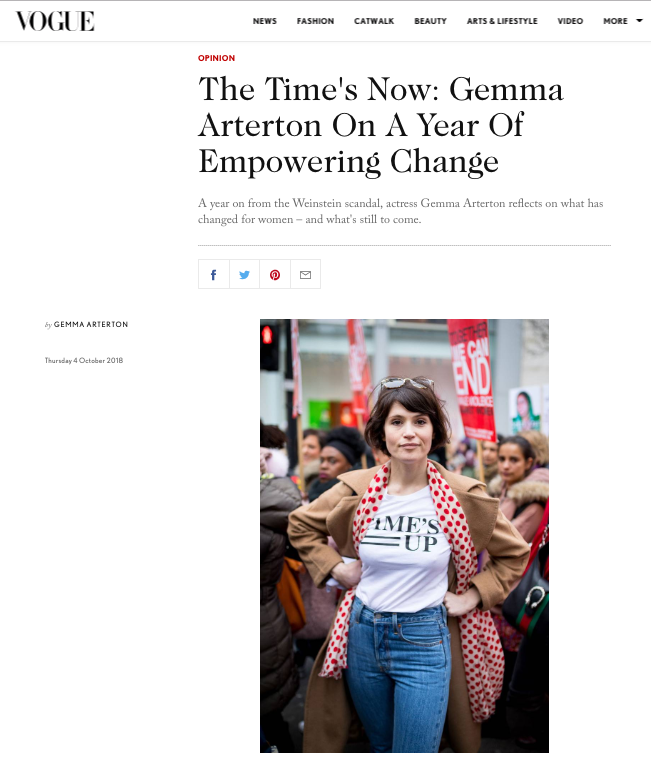

Leading beauty magazine Elle, for example, has started publishing in-depth features, such as their year long report titled ‘The Warriors’ which tells the stories of Women around the globe fighting for their rights; this report also headlines the website. Meanwhile, in a recent issue of British Vogue, Gemma Arterton wrote about the year of female empowerment – centering on the Time’s Up movement. Drawing in thousands of readers because of their importance in contemporary society – and in turn increasing revenue for brands – it’s apparent these social issues are front cover worthy.

In some ways, mainstream magazines have always talked about social issues. The difference is now they are beginning to give under-represented females across the world a platform to voice their stories and views.

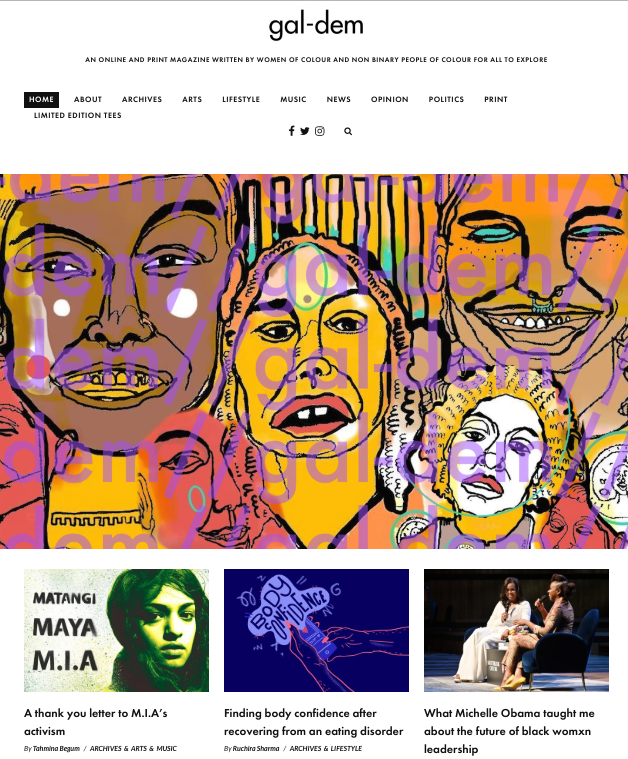

The emergence of platforms such as Gal-Dem, The Pool and Broadly has highlighted that there is (and arguably has always been) a large demographic of female readers not interested in hearing how many pounds the TOWIE cast has lost, and wanted to read more substantial, thought-provoking features that cover a range of international affairs.

|

Understanding readers’ needs

In response to the success of these newer titles, more established platforms – including international newspapers – began shifting the focus of their content to maintain their readerships.

Natasha Bird, digital editor of Elle UK, believes ignoring the political and social inclinations of the magazine’s readership can be regarded as a bad business decision.

Natasha said: “There is now a wealth of research out there to suggest that among the educated millennial audience we serve, feminism (and a wider interest in politics) is way more than just a superficial fad. In fact, it would be a laughable over-simplification to even call it a ‘trend.’

They [women] want to feel like magazines understand their struggle, represent their needs, will fight with them on the front line against the injustices which they are experiencing. They also want to feel like they aren’t being lied to, that you will be an authentic voice in a sea of people trying to take them for a ride.”

Natasha says there has been a lot of angry commentary recently, regarding ‘fauxpowerment’ and ‘false feminism’ – which she believes is misdirected.

“From my perspective, any popular movement will spurn people to either copycat or cash in. That’s a given. And so what? In this context, it doesn’t mean that feminism or social change isn’t also happening for real,” Natasha added.

Meanwhile, Farrah Storr, editor-in-chief of Cosmopolitan Magazine, believes the role of magazines has been and should always be to both represent and make sense of what is happening in modern culture. Farrah said: “Feminism, the fight for free speech, social justice – these are the biggest debates we are having right now and so it’s vital that women’s magazines should cover them with solid, impartial reporting.

“Whether we like it or not, the cultural agenda is increasingly set by social media. And that can be dangerous. So, the role of any editor, whether the editor of a newspaper or a women’s magazine, is to sit back, analyse the debate, then report it back to our consumers with impartiality.”

Lily O’Farrell, founding director of independent Feminist illustration platform ‘Vulgar Drawings,’ has recently launched an online shop following the success of her brand on Instagram, believes, “I think women have always been interested in feminism as a concept, whether it has come under the term ‘feminism’ or not.”

Lily believes the popularity and growth of these topics within women’s publishing isn’t a trend, and that it is mirroring the gradual acceptance of a women’s voice (a process that has slowly been growing in western society since first wave feminism in the 19th century), and a demand for it within society.

“This isn’t a phrase, hopefully the two will continue to merge (such as the Gal-dem takeover in The Guardian) and women will have more control,” she added.

The role of technology

Academics and researchers believe the technological revolution has a large part to play in the coverage of these issues.

Gender and Power Professor at The University of East Anglia, Helen Warner, believes that independent female empowerment magazines have existed for a very long time (think Spare Rib which gained popularity in the 1970’s), and will continue to do so, assuming technology will carrying on driving exposure and therefore a diverse readership. She also believes that mainstream media still has some way to go before if truly reflects the diversity of all of its audience.

Professor Warner said: “Women and non-binary folk have always created their own content because mainstream media have historically sidelined their interests/represented them poorly – if at all!

You need a space like Gal-dem written by and for women of colour when it takes publications like Vogue over 100 years to feature a black woman on the cover of their September issue. What we’re seeing now is perhaps increased visibility of these kinds of media texts thanks to technology but they’ve always been there.”

“I think feminist media content needs to do something to actively challenge systems of domination and oppression. Women and girls will continue to make their content. What I’m not sure about is if they will be adequately compensated for doing so. Often, these independent magazines rely on a huge amount of invisible (unpaid) labour. If it was the case that a bigger corporation could support them, I’d question whether they would be able to continue the important feminist and anti-racist work they’ve been doing.”

|

Ultimately though Farrah Storr, editor-in-chief of Cosmopolitan Magazine, argues that if a topic has prominence in culture then it has a place in women’s magazines; as Women become politicised in different ways, then Women’s magazines should reflect this movement.

“That does not mean Cosmo is suddenly a political magazine, but it has always been a magazine that explores and charts the cultural climate. That is what we are doing now by covering these subjects.

The vast number of platforms that we [Cosmo] are across allows us to see and hear exactly how interested our consumers are in these subjects. In the last year we’ve had almost a million views of content with the words feminist, feminism, sexist and sexism in their URL whilst a survey we ran on domestic abuse was viewed over 3.5 million times across the website and Snapchat discover.”

This story is authored by Harriet King, MA Global Intercultural Communications at University of East Anglia.

More like this

Hearst: the future of the luxury market will depend on Chinese millennials

Nancy Spears, CEO of genconnectU, on when and how to pivot

How Paris Match uses legacy storytelling to find success on Snapchat