Crowdsourcing: How The Guardian, ProPublica and Vox Media are doing it

The same year Twitter launched in 2006, Wired writer Jeff Howe coined the term “crowdsourcing”. The term has been around for more than a decade, and the practice of ‘tapping into the collective intelligence of the public at large’ is still being used by researchers, journalists and publishers alike – daily.

Pre 2006 (pre social media and other online sources) it was much harder for storytellers and journalists to get by on the right information, and credible resources, for a good story. Getting something newsworthy meant heavily relying on news tips and word of mouth to scoop a story as it broke. Today it has become somewhat easier; a quick search online can bring up vast quantities of relevant information and images that might have been otherwise unavailable. Today, verifying whether or not something is newsworthy to your readers, can be done with a simple tweet – as seen below.

Autism Awareness Week: share your experiences https://t.co/bqn0XJcD1g

— The Guardian (@guardian) March 27, 2018

The internet and social media has become a kind of free-for-all information library that’s updated by people from around the world, 24 hours a day. Because the normal man in the street can be at a scene sometimes long before journalists are, it becomes an important source of information – especially on online news and social networking services like Twitter. For storytellers and journalists this could mean more complete and more comprehensive research when tapping into online sources. It could also mean more engaging content for readers.

Screenshot Twitter; Rolling news updates on #CambridgeAnalytica as it happens on Twitter

According to the American Press Institute, the best stories contain more verified information from more sources, with more viewpoints and expertise. They exhibit more enterprise and more reportorial effort. Which is where crowdsourcing comes in. The Columbia Journalism School defines crowdsourcing best:

Journalism crowdsourcing is the act of specifically inviting a group of people to participate in a reporting task—such as newsgathering, data collection, or analysis—through a targeted, open call for input; personal experiences; documents; or other contributions.

Publishers who crowdsource

Publishers are doing exactly this – inviting people to contribute to their reporting tasks. Not only for research purposes, but to get the right angle with various viewpoints to make stories more significant, more relevant and more engaging. Prime examples of publishers using media crowdsourcing in journalism include The Guardian, ProPublica and Vox media. Here’s how they do it.

1. The Guardian

Apart from the already given Twitter crowdsourcing example, The Guardian uses Reader Questions in their articles to crowdsource which topics their audience would like more details on. Based on votes, editors can shape future coverage whilst also having a better understanding of their readers’ interest. In a recent article on Facebook’s mistakes over Cambridge Analytica, they had the following embedded poll at the end of the article:

Screenshot The Guardian; Reader Questions embedded in Facebook’s mistakes over Cambridge Analytica article.

In an article by DigiDay UK, Guardian publishers said that each question on their site has thousands of reader responses, amounting to nine per cent of people on average who see the question. In some cases, this rises to 20 per cent. A nice way to gauge reader interest for possible follow-up articles.

2. ProPublica

In another crowdsourcing example, ProPublica asked for reader input for their piece Lost Mothers – an engaging piece of journalism that explores reasons why the US has the highest rate of deaths related to pregnancy and childbirth in the developed world. Getting reader input was key to making the project a success – and in one year over 5,000 stories were submitted by readers. How they did it meant crossing traditional and engaged journalism as they reached out to partners (like the NRP) to put the word out there for crowdsourcing input. In the below example, Facebook was amongst the platforms used.

3. Vox Media

At Vox Media, a similar approach to crowdsourcing is taken – with Twitter being the prime source of crowdsourcing. Liz Plank, senior producer and correspondent, used crowdsourcing to ask for female experts’ input on a very specific topic – Rwanda and the state of gender equality in the country after genocide. Another reporter, Johnny Harris, used crowdsourcing on social media to explore the impact that borders have on people living on either side of them. It netted 6,000 replies from around the world.

We have our six border locations! Submit your ideas of what I should see while I’m traveling. https://t.co/rwAiWEb5zI pic.twitter.com/8iwv2P2L8r

— Johnny Harris (@johnnywharris) June 2, 2017

Limitations in crowdsourcing

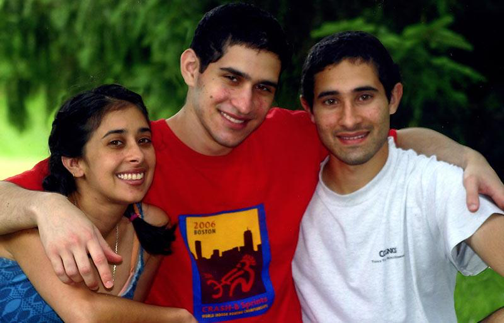

That said, crowdsourcing also has its limitations. When audience’s entry points into a journalistic process is false, but are taken as truths, the implications can cause serious damage. An example of this is crowdsourcing that took place during the Boston bombing, where innocent men were falsely identified as suspects in the days after the bombing. Like Sunil Tripathi, who was mistaken as one of the bombers due to misinformation on Reddit.

As with Tripathi, unverified crowdsourcing, poor journalism and social media led to irresponsible speculations causing varied amounts of damage to those involved. It is thus crucial that when journalists and storytellers crowdsource, it has to be done right.

|

Image credit: Columbia Journalism Review. The Tripathi siblings: Sangeeta, Sunil, and Ravi.

Crowdsourcing done right

To present “the facts” and the “truth about the facts,” journalists and storytellers need to practise a discipline of verification. For crowdsourcing, the TOW Center for Digital Journalism has six different calls to action they follow to verify information, as given in their Guide for Crowdsourcing:

- Voting—prioritising which stories reporters should tackle.

- Witnessing—sharing what you saw during a news event.

- Sharing personal experiences—telling what you know about your life experience.

- Tapping specialised expertise—contributing data or unique knowledge.

- Completing a task—volunteering time or skills to help create a news story.

- Engaging audiences—joining in call-outs that can range from informative to playful.

The “sharing (of) personal experiences” also means giving credit where it’s due and verifying original sources of information. Due to reaps of content available online, especially on platforms like Twitter, and deadline driven stories that needs to get published – research time is often limited. To help with this publishers are turning to software solutions to sift through the clutter and determine what’s valid, and what’s not.

In the case of Emma Gonzalez’s most recent cover shoot with Teen Vogue, social platform Gab posted what they called “a parody/satire” where, instead of ripping a target poster, Gonzalez is ripping the Constitution. With over 1,500 retweets and 3,000 likes (at the time of writing this piece), exposing the source of the smear campaign proved to be just as important. What can help with this?

|

Since posting this piece, this tweet has been removed.

Solutions for crowdsourcing

When practicing crowdsourcing, journalists and storytellers’ jobs can be made easier with things like software and external platforms. Publishers who turn to these solutions for crowdsourcing are not only getting it right, but getting it right faster for quicker turnaround times on breaking news stories.

1. A software solution for crowdsourcing

An example of software used for crowdsourcing includes Elvis Digital Asset Management (DAM). When integrated with things like Twitter and artificial intelligence (AI), images for breaking news stories can be sources faster by:

- Eliminating irrelevant content

- Verifying images quickly

- Citing sources with automated links to Twitter.

See how it’s done here.

2. A platform solution example for crowdsourcing

Platforms used for crowdsourcing more sensitive information – like that provided by whistleblowers – includes solutions like SecureDrop. Media organisations use the platform to securely accept documents from, and communicate with, anonymous sources. These solutions, along with objective storytelling and ethical journalism, can help with good, engaging, storytelling.

With the rise of the internet correlating with the rise of crowdsourcing, technologies have made good journalism easier. Identifying sources, getting the right research and following breaking-news developments as it happens provides varied angles that wasn’t available pre social media and the internet. With the right technology tools and software solutions, it can be even easier for publishers to crowdsource information and gather, assess, create, and present news and information to readers in ways they’ve never experienced before. Are you doing crowdsourcing right?

This article is authored by Madre Roothman, product marketing manager at WoodWing.