The Mr. Magazine™ interview: Wired’s editor-in-chief Nick Thompson on the roadmap to magazine success

This year, Wired Magazine will celebrate 25 years of publishing some of the best content in the world of technology. And this year, the brand will also inaugurate its editor in chief’s latest edition to the business model: a paywall. For over six years, Nick Thompson was an editor for newyorker.com and learned the art of the paywall; and the benefits. Bringing that knowledge to Wired, where he has run the tech-ship for just over a year, he has constructed a new revenue source that he’s hoping will prove that people are willing to pay for quality content, for something they value and that adds value to their lives.

On a recent trip to New York, I spoke with Nick about the changes he’s implemented, such as the paywall. For a tech-savvy man, Nick is a rare breed, because he also believes in the power of print. So, Print Proud Digital Smart is just common sense to him, and Mr. Magazine™ would have to agree. And Mr. Magazine™ also believes in the value of content, just as Nick does. So, the paywall, while tried and failed by many before him, seems possible with the determination and vision that Nick possesses. Not only possible; probable, but also success-able.

From an email to Wired subscribers, and in Nick’s own words, he had this to say about the paywall: “As you may have seen in the press, we’re launching a paywall on Wired.com—an important and exciting step that will allow us to continue our great work for the next quarter-century and beyond.” Indeed, if the next 25 is anything like the first 25, everyone will be willing to “pixel-up.” And now the Mr. Magazine™ interview with Nick Thompson, editor-in-chief, Wired. Enjoy!

|

But first the sound-bites:

On why he thinks it took the industry so long to change from a welfare information society where everything digital was given away freely to one that charges for its online content: I think business was really good in the old model for a long time. We made a lot of money from advertising and it took a while for the industry to realise the problems with that. And it took a long time for the industry to realise that digital advertising wouldn’t replace it. I believe we came to those realisations too slowly.

On the secret of Wired’s longevity: That’s an interesting question. It’s always been really good, that’s the first thing. When it had rough patches, it figured its way out of them. It never found any of the traps of some of the other tech publications. It had Condé Nast supporting it as well. And because it had been relatively early, it had a lot of loyal supporters and backers. So, it’s always had a really good and strong fan base, and it’s always had a great group of writers.

On Condé Nast’s handling of Wired over the years, and the fact that when most bigger companies buy small, entrepreneurial publications, they end of folding them, but not in the case of Wired: I wonder about that. I think that reflects very well on Condé Nast. They changed editors; they did all of the things that usually happen when a rogue publication is bought by a big company. They changed editors; they changed philosophy, but I think they kept a hands-off approach. A lot of people stayed through; the magazine stayed in San Francisco, and I think Condé Nast realised the independent spirit that Wired had, and managed it well.

On how he would define content today: That’s a good question. You have to think about all of the different places where we publish unique content. There’s the print magazine; the website; the Snapchat channel; the Instagram feed; there are all kinds of things. There are videos that we’re making for Facebook live; YouTube videos that we’re creating. So, it’s all Wired content; it’s all Wired “stuff” and my involvement in it ranges from the print, where there’s a lot, to social where there’s less. And then I’m participating in a lot of it. I’ll do some of the Facebook lives or some of the discussions.

On whether he feels he’s more of a curator today than a creator: No, more of a creator, but the curation is part of it too, because part of what you do is figure out how things should be promoted; what should go in the newsletter; how the newsletter should be structured. I write my own newsletter; I do my own Tweets; I do Facebook; so, there’s that part of the curation element. But most of what I’m doing is writing and editing.

On the biggest stumbling block he’s had to face, or whether it has it all been a walk in a rose garden: You need to do three things when you’re in my job: you need to create the right stories; you need to get them out to people in all the right ways; and you need to build a business model around that. And I feel like we’re creating the right stories and that we’ve built a business model, but I’m not sure that we’ve optimised getting ourselves out there in all the right ways. So, the biggest challenge is how do you get people to read your content on a mobile device? Some people will go to your website on a mobile device, but mostly they’ll go to your Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, or they’ll come in through an app.

On the iPad and how Wired was one of the first Condé Nast titles to jump onboard: And it was awesome. My predecessor, Scott Dadich, he designed that, and did a killer job. The issue is, back then we all thought the iPad was the future of magazine reading, right? And that people would have iPads and they would download all of the magazines. But as it turned out, the iPad wasn’t; it turned out to be the phone. The question is, can you take the iPad version and make it work on the phone, that’s something that we need to do here, because we have a great iPad app, but we don’t have an iPhone app.

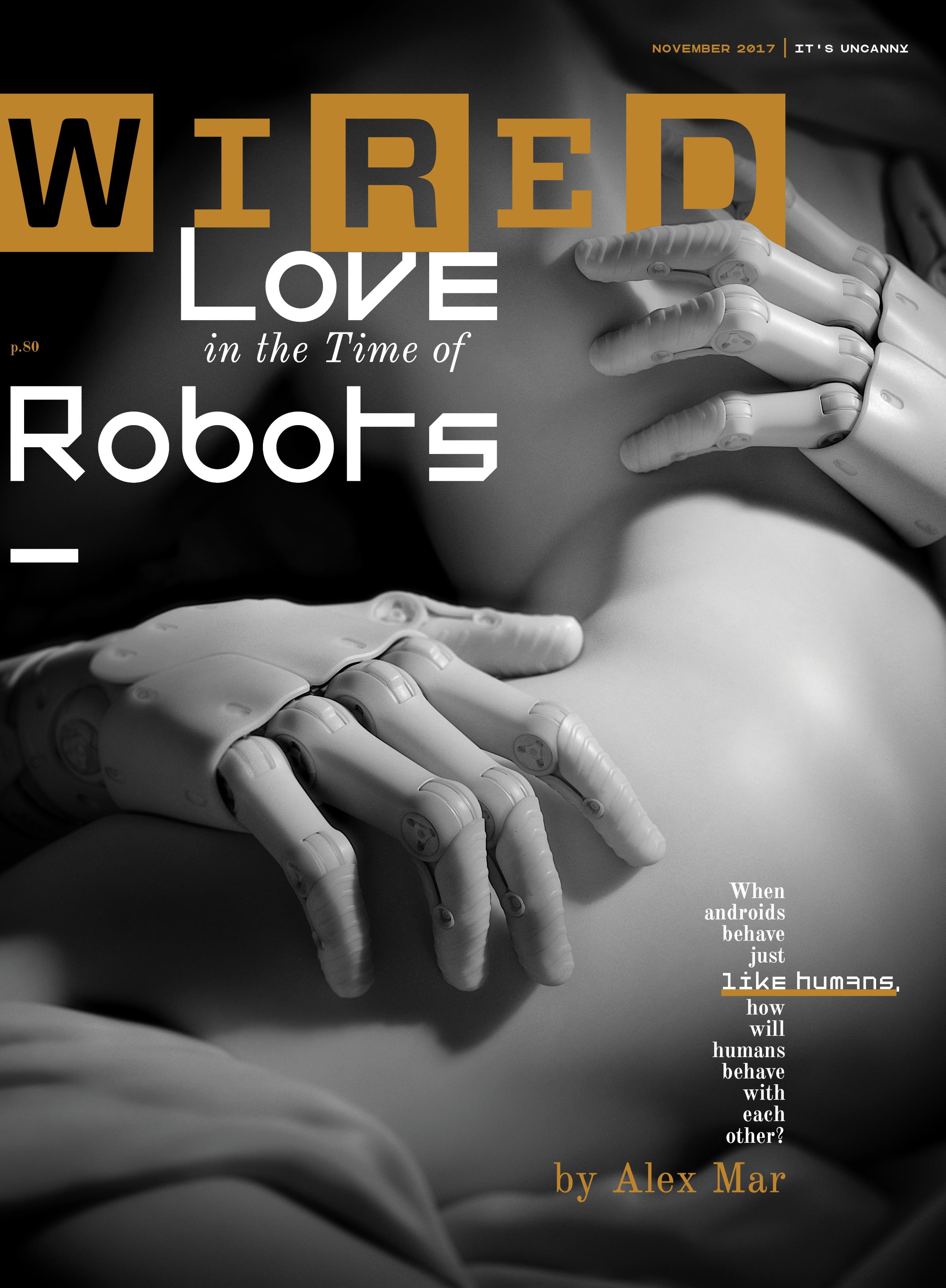

On how he decides what content goes where and if dissecting that content is getting easier or harder: In the old days, content was created for print and dissected for the other platforms, and here it’s more that we try to come up with content that works on all of the platforms, starting from an idea. The Free Speech package was definitely something we came up with for the print medium, because the idea on how to do it was a big structured thing around it, and that still works when you have the excuse of a print magazine that gets mailed to 850,000 people, and that has a cover and a set number of pages. So, we decided to do that and spread it out on all of the other platforms.

|

On why he still believes in print: There are a couple of reasons. Number one, because I spend a lot of time on tech, I realise its limitations. You can put out a Tweet and you can look and say that you have 10 million Twitter followers; that Tweet is going to reach 10 million people, but actually it’s not. A thousand people are going to click on it, or 200 people are going to click on it. So, there are real distribution issues on all platforms. When you think about it that way, it helps you remember that the US Postal Service that will deliver 850,000 copies of these to people’s doors, or whatever the exact number is right now, is a pretty good distribution mechanism.

On how he edits the magazine to cater to the geeks and the intellectuals simultaneously: That’s the whole challenge of this job. It’s to cater to both of them and even to people who are coming to technology for the first time. And that’s a challenge with our web content and that’s a challenge with Snapchat content; that’s a challenge with everything we do. That’s less of a print challenge than it is an overall Wired challenge. And there, we try to think of ourselves as a magazine about change, not as a magazine about tech. We think about the way technology is changing our lives; changing our world and the way that we relate to each other. Find the most interesting questions and answer them in the smartest way that we can, in whatever form is appropriate for whatever medium we’re writing for.

On how his job as a magazine editor, especially of Wired, is different today than it was some years ago: The first difference is that, obviously, we’re publishing in more different ways. And the world only gets more complicated; the job only gets more complicated; and your time only gets more disbursed, because you’re not doing a print magazine, you’re doing a print magazine and a website and all of these social platforms. So, that’s different.

On one moment he can reflect on since he’s been editor where he thought the magazine was at the exact place he wanted it to be: This month has been amazing, because I think our Free Speech issue conveys exactly what I want to do with the magazine. It has five essays, all of which are awesome; they read really well together. I think it’s one of the smartest packages put together on free speech.

On whether he thinks it will be smooth sailing from now on: (Laughs) I don’t think any editor in this business would think it’s smooth sailing from now on. We have to think about what comes next, so we have to make the paywall work. We’re just days in and it looks good so far, but that’s nothing. We need to make sure that we optimise and that we figure out the right ways to promote it; that we reduce friction in the subscription process; that we improve re-circulation; that we assign the right content; and that is really hard. Then we also need to figure out how to continue to diversify our revenue streams.

On whether he feels like in his job now he has to hop on and off the train without it ever stopping: (Laughs) No, I feel like the train still stops. Maybe in two years the train won’t stop and I’ll be jumping out the window. Right now it’s okay. It’s funny, because I don’t think the job of editor-in-chief of Wired will ever get less complicated, because you have to be in the middle of the way technology is reshaping the world, and the nature of technology is that it accelerates, because when you invent something it helps you invent the next thing.

On why he thinks the whole media world is suddenly watching Wired and its new paywall to see if it succeeds or fails: I think the fact that it’s Wired and we’re considered to be at the forefront of technology makes a big difference. I think to some people it’s surprising. You may think that Wired would always make its information free. Though, since the very beginning Wired has talked about the value of content and whether it’s important to make people pay. And there’s a huge debate among the early Wired founders. I’m glad people are paying attention. The more attention, the better.

On what someone would find him doing if they showed up unexpectedly one evening at his home: You’ll find me reading magazine stories on my phone, if I’ve finished my work. I tend to go home and work; I work here, then I go home and put my kids to sleep, and I tend to go back to work, in part, because I work with a lot of people in San Francisco, so my 10:00 pm is their 7:00 pm, so we’re synced up pretty well. And I tend to work until 10:00 or 11:00 pm. And if I finish and have some time, I like to read magazine stories in other publications. And I like to play guitar.

On what he would have tattooed upon his brain that would be there forever and no one could ever forget about him: That I actually really care about my job. I care about Wired because I think it’s really important for society to have these conversations about technology, such as free speech and technology. And I feel like Wired plays a really important civic role. So, I want them to realise that what excites me about this job and what I do isn’t just because it’s a cool job and I work in media. It’s because there’s real civic value in having this thing work and to do it well. And that’s why I try.

On what keeps him up at night: I don’t think any editor-in-chief of any publication sleeps well, with the business changes over the last few years. I worry a lot that we get stories right and I worry a lot about what comes next for us. What are the product, engineering and business choices we need to make to be sure that we can continue to produce really great journalism. So, that keeps me up at night.

And now the lightly edited transcript of the Mr. Magazine™ interview with Nick Thompson, editor-in-chief, Wired.

|

You’ve been in the news a lot lately for doing what I’ve always called a common sense thing; if you have good content, people will pay for it. Why do you think the industry waited so long to change from a welfare information society where we give everything away for free to finally charging for content?

I think business was really good in the old model for a long time. We made a lot of money from advertising and it took a while for the industry to realise the problems with that. And it took a long time for the industry to realise that digital advertising wouldn’t replace it. I believe we came to those realisations too slowly.

Specifically with Wired, as you approach your 25th anniversary; a lot of tech magazines have started up and folded during that same period, all trying to captivate the future of technology and humanising technology. What’s the secret of Wired’s longevity?

That’s an interesting question. It’s always been really good, that’s the first thing. When it had rough patches, it figured its way out of them. It never found any of the traps of some of the other tech publications. It had Condé Nast supporting it as well. And because it had been relatively early, it had a lot of loyal supporters and backers. So, it’s always had a really good and strong fan base, and it’s always had a great group of writers.

I don’t know, I feel like it never even came close to going away. It’s been a good publication with lots of supporters the whole way through, lots of advertisers; a good subscription base. It’s been healthy and strong and it’s managed to never completely screw things up.

From an historical point of view, when I study all of the magazines that were started by entrepreneurs and sold to big companies, the bigger companies managed to mess them up and fold them. That’s not the case with Wired.

I think that reflects very well on Condé Nast. They changed editors; they did all of the things that usually happen when a rogue publication is bought by a big company. They changed editors; they changed philosophy, but I think they kept a hands-off approach. A lot of people stayed through; the magazine stayed in San Francisco, and I think Condé Nast realised the independent spirit that Wired had, and managed it well.

So, I think it reflects well on Condé Nast and I think it reflects well on the Wired team and it reflects well on Katrina Heron, who took it over after the transaction, and then Chris Anderson, who succeeded her.

As you are moving Wired toward the next quarter of a century, you started by adding a paywall; you’ve been quoted as saying print is not going away, that you still believe in it. So, as an editor today, how do you define content?

That’s a good question. You have to think about all of the different places where we publish unique content. There’s the print magazine; the website; the Snapchat channel; the Instagram feed; there are all kinds of things. There are videos that we’re making for Facebook live; YouTube videos that we’re creating.

So, if you were to look at my to-do list for today, I have to read some of the drafts for the next issue of the print magazine; I’ve got to read a bunch of web posts that have gone live, make sure they’re good and figure out how to promote them and how to help the writers improve, or how to work with the writers. I have to think about all of the social media platforms. So, it’s all Wired content; it’s all Wired “stuff” and my involvement in it ranges from the print, where there’s a lot, to social where there’s less. And then I’m participating in a lot of it. I’ll do some of the Facebook lives or some of the discussions.

There’s way too much content for any single human to be involved in, so I just have to figure out how to allocate my time in a way that is most effective, both for specific editing and the more general sense of conveying my view of what a Wired story is. And then the general coaching, managing and cheerleading the staff and all of the stories.

Do you feel you’re more of a curator today, rather than a creator?

No, more of a creator, but the curation is part of it too, because part of what you do is figure out how things should be promoted; what should go in the newsletter; how the newsletter should be structured. I write my own newsletter; I do my own Tweets; I do Facebook; so, there’s that part of the curation element. But most of what I’m doing is writing and editing.

There are 100 different things that could be a part of my job and I try to think about all of them. And I try to weigh whether I can actually be helpful with #96 on the list of things, and if I can, I’ll spend some time on it and if I can’t, I’ll let it be.

What has been the biggest stumbling block that you’ve had to face since you took over the editorship and how did you overcome it? Or has it been a walk in a rose garden?

I’ve been really happy with the print magazine for the last few months. I feel like we’ve gotten a really strong feature well, and we’ve gotten really good covers. If you look at our next cover, which I shouldn’t talk about, but I think it will be exciting. And our free speech cover; the cover about China; the cover on our issue now. We’ve done really good issues. And when I started, it wasn’t like they were bad, they were still good.

But I feel like there has been steady improvement in making sure that the feature well, in particular, has grown and become really close to what I wanted it to be when I started this job. So, that’s good, but it was also really hard, so maybe that’s the answer.

The other thing that’s hard is obviously, you need to do three things when you’re in my job: you need to create the right stories; you need to get them out to people in all the right ways; and you need to build a business model around that. And I feel like we’re creating the right stories and that we’ve built a business model, but I’m not sure that we’ve optimized getting ourselves out there in all the right ways. So, the biggest challenge is how do you get people to read your content on a mobile device? Some people will go to your website on a mobile device, but mostly they’ll go to your Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, or they’ll come in through an app.

We don’t yet have a custom IOS app. We have read platforms or a progressive web app, which makes our Android reading experience much better, but we were a little late to optimise ourselves on mobile devices. So, that’s something that we’re working hard on, but we haven’t completely solved yet.

In my ideal world, there would be a fantastic, beautifully-designed way to read Wired through Flipboard, Apple News, Facebook Instant, an IOS app, an Android app, and a progressive web app, but we don’t have that whole suite of things yet. We have some of them, but they require design, product, engineering and business, and so they’re really complicated to get right.

I remember when the iPad first came into being back in the dark ages of 2009, Wired was a forerunner. I think it was the first Condé Nast magazine to jump onboard.

And it was awesome. My predecessor, Scott Dadich, he designed that, and did a killer job. The issue is, back then we all thought the iPad was the future of magazine reading, right? And that people would have iPads and they would download all of the magazines. But as it turned out, the iPad wasn’t; it turned out to be the phone. The question is, can you take the iPad version and make it work on the phone, that’s something that we need to do here, because we have a great iPad app, but we don’t have an iPhone app.

|

With your role, and the many hats that you wear, how do you decide what content goes where? From print to digital, and now with the paywall; is dissecting the content getting easier or harder?

In the old days, content was created for print and dissected for the other platforms, and here it’s more that we try to come up with content that works on all of the platforms, starting from an idea. The Free Speech package was definitely something we came up with for the print medium, because the idea on how to do it was a big structured thing around it, and that still works when you have the excuse of a print magazine that gets mailed to 850,000 people, and that has a cover and a set number of pages. So, we decided to do that and spread it out on all of the other platforms.

But there are elements of Wired taking on the issue of free speech that have been native to other platforms, like Facebook Instant conversations and Reddit AMA’s. There have been all kinds of interesting elements and add-ons that doesn’t feel as though we’re cutting a piece of meat off of the bone of the big animal. We feel like we actually made a meal for that particular platform.

You’re one of the few editors of a tech magazine who still believes in print. Why?

There are a couple of reasons. Number one, because I spend a lot of time on tech, I realise its limitations. You can put out a Tweet and you can look and say that you have 10 million Twitter followers; that Tweet is going to reach 10 million people, but actually it’s not. A thousand people are going to click on it, or 200 people are going to click on it. So, there are real distribution issues on all platforms. When you think about it that way, it helps you remember that the US Postal Service that will deliver 850,000 copies of these to people’s doors, or whatever the exact number is right now, is a pretty good distribution mechanism. The US Postal system and the whole method of people subscribing, they get 12 issues per year, that’s really great. So, that’s one reason.

Number two is there’s something about the print magazine that’s special. It’s got the front cover, which is a way to really make a statement. It has a back cover that advertisers love. It has the capacity to package things, because the Internet breaks everything up, so the capacity to keep things together is really valuable. And advertisers see that too.

And then there’s something about the discipline of putting together a print magazine which is a useful exercise to go through for content. So, having strict limitations on the number of words that you can put in a story is actually good for the story often. Sometimes it’s nice to have unlimited words, but sometimes not having constraints leads to softness in the way you edit it or the way you think about it. Print magazines still do some really good things. My hope would be that we’ll continue to run the print magazine as long as I’m in this job, and that even if the advertising goes down in print, we’ll be able to make up for it in subscription revenue. Right now, it’s a profitable product and I think a really good product.

How do you manage to create this curated, well-packaged issue, month after month, that caters to the geeks of technology and to the intellectuals of technology simultaneously?

That’s the whole challenge of this job. It’s to cater to both of them and even to people who are coming to technology for the first time. And that’s a challenge with our web content and that’s a challenge with Snapchat content; that’s a challenge with everything we do. That’s less of a print challenge than it is an overall Wired challenge. And there, we try to think of ourselves as a magazine about change, not as a magazine about tech. We think about the way technology is changing our lives; changing our world and the way that we relate to each other. Find the most interesting questions and answer them in the smartest way that we can, in whatever form is appropriate for whatever medium we’re writing for.

On the web, you want to write about things that are happening in the present; you want to write about things that are current. In print, you need to write about it in a format that will be relevant two weeks after the story closes or five weeks after the story closes, because that’s when the person actually picks up the pile of mail at the apartment they’ve been traveling from.

You have the same challenge; how do you make the story interesting for all of these different readers? And then you just have different constraints and different kinds of form based on where you’re publishing it.

How would you describe the job of a magazine editor today, especially Wired? And how is it different from some years ago?

The first difference is that, obviously, we’re publishing in more different ways. And the world only gets more complicated; the job only gets more complicated; and your time only gets more disbursed, because you’re not doing a print magazine, you’re doing a print magazine and a website and all of these social platforms. So, that’s different.

But the core is kind of the same. Your job as the editor in chief is to help set a vision with your team; it’s to hire the right people, who do all of the right jobs; it’s to help people grow as writers and editors, to the extent that you can. It’s to be an ambassador, so that’s why you go to different places, like Davos, which I just returned from, to meet people; and it’s also to find really good stories, which is another reason to go to a place like Davos.

Part of my job is to sit at my desk and help move copy along and to read things and to help edit them. And then part of my job is to go out into the world and be a public face for Wired and talk to people about Wired and learn about the kind of issues we should write about. So, you have to just balance your time.

There are different kinds of editors. David Remnick, who I obviously observe very closely, spent a ton of time writing stories, editing stories, and also a ton of time promoting them, like on The New Yorker Radio Hour and on television and radio. Other people focus more on one element, like Adam Moss, who is an absolute genius at how he puts together New York magazine, but he’s not as much out there talking on television or on the radio. He’s just kind of in his office making the thing amazing. So, there are different roles. And the way I’ve chosen to do it is to do lots of things, maybe for good or for ill.

During this short period since you’ve been editing Wired, can you reflect on one moment where you said to yourself, wow, this is the Wired I want?

This month has been amazing, because I think our Free Speech issue conveys exactly what I want to do with the magazine. It has five essays, all of which are awesome; they read really well together. I think it’s one of the smartest packages put together on free speech.

And free speech is something that I really don’t have a handle on. I know that the view on free speech in the tech industry has massively changed. I know that it’s complicated, but I came to it not thinking that “we need to stand up and really fight against the way the tech companies are now censoring.” Or “I really think that debate about free speech is going in the right direction.” I was very conflicted when we started this package. I felt really good that we put together an issue that had these five essays; the cover worked and the whole issue felt right. So, I felt great about that.

And then we went to the paywall and we actually hit our deadlines and the early returns are great. So, January and the first couple of days of February have been fantastic for Wired. I feel like we put out a great issue and we created a new business model, which is something I talked about my first day on the job. And it came to fruition.

Is it smooth sailing then from now on?

(Laughs) I don’t think any editor in this business would think it’s smooth sailing from now on. We have to think about what comes next, so we have to make the paywall work. We’re just days in and it looks good so far, but that’s nothing. We need to make sure that we optimise and that we figure out the right ways to promote it; that we reduce friction in the subscription process; that we improve re-circulation; that we assign the right content; and that is really hard. Then we also need to figure out how to continue to diversify our revenue streams.

What we’ve done this year is try to grow advertising as much as possible. I’ve worked very carefully with our business side to understand what we do in advertising and what works. And what we can do more of; where are there opportunities for growth. But at the same time, trying to diversify. So, we started an affiliate revenue stream, where we massively expanded our efforts. If you read a review on the best headphones at Myer and you click on one and buy it, we get a small cut. And that’s useful.

Now we have three really good revenue streams, but the question is a year from now we’ll want to have diversified even more. We’ll want to have done better in all the things we do, but we’ll also want to have other revenue streams. So, what will those be? Wired has very limited audio efforts; should we go hard in that? There are a couple of other things that we’re looking at; a relatively limited conference business. We do one big event, but other publications that are similar to us do lots of events; should we do that? It’s competitive, but we could do more of that. And then there are a whole bunch of other things that we’re thinking and talking about.

One of my big questions for next year is what’s next? From the product and engineering side of my job, we’ve had two big products. First, we moved our CMS’s (content management systems) to the corporate CMS’s “Copilot,” which was a huge project and that was really the first six months of my job. Then the next six months was the paywall. So, now the product and engineering roadmap is complicated and the business roadmap is complicated.

Meanwhile, you can’t let your foot off the gas and spend so much time thinking about these things, or have your team spend so much time thinking about them, that you let the other stuff slide, and you have days where the website isn’t interesting or the magazine isn’t good. You don’t ever want that. So, that’s the challenge. It’s not like the old days where you just hire 100 new people or something. You have to do evermore within constraints, real constraints.

|

Do you feel in your job now that you have to hop on the train and hop off the train without the train ever stopping?

(Laughs) No, I feel like the train still stops. Maybe in two years the train won’t stop and I’ll be jumping out the window.

Right now it’s okay. It’s funny, because I don’t think the job of editor-in-chief of Wired will ever get less complicated, because you have to be in the middle of the way technology is reshaping the world, and the nature of technology is that it accelerates, because when you invent something it helps you invent the next thing. And so technology will constantly be creating, so the train only moves faster and the job only gets harder. So, ask me that in three years. (Laughs)

Do you feel that you are living in a glass house now, because everybody is watching you. With all of the other entities that tried paywalls and other things like that, they weren’t talked about as much as Wired. Is it specifically because it’s Wired or because it’s Condé Nast? Why do you think that the entire media world is watching you to see if you’re going to succeed in this experiment or fail?

I don’t know. Maybe because I talk about it a lot. (Laughs) I’ve given lots of interviews about paywalls; I talk about it all of the time and I care about it a lot. I felt like my experience at The New Yorker was one of the most interesting things I’ve ever done, so I speak about it a lot and I feel good about what we did at The New Yorker. So, that probably helps a little bit.

I think the fact that it’s Wired and we’re considered to be at the forefront of technology makes a big difference. I think to some people it’s surprising. You may think that Wired would always make its information free. Though, since the very beginning Wired has talked about the value of content and whether it’s important to make people pay. And there’s a huge debate among the early Wired founders. I’m glad people are paying attention. The more attention, the better. And I hope that people subscribe. We’ll see. And if it doesn’t work, it doesn’t work, but it’s already worked. We’ve already gotten tons of new subscribers and we’re just days into it.

When Wired was started it had a massive subscription price and you couldn’t even get it billed; you had to pay before you received the magazine.

When I launched the paywall, I got a note from the guy who founded the magazine saying that people should be willing to pay for the stuff that they spend their time with and value. You’re adding value to people’s lives and they should be willing to pay for it.

If I showed up unexpectedly at your home one evening after work, what would I find you doing? Having a glass of wine; reading a magazine; cooking; watching TV; or something else?

You’ll find me reading magazine stories on my phone, if I’ve finished my work. I tend to go home and work; I work here, then I go home and put my kids to sleep, and I tend to go back to work, in part, because I work with a lot of people in San Francisco, so my 10:00 pm is their 7:00 pm, so we’re synced up pretty well. And I tend to work until 10:00 or 11:00 pm. And if I finish and have some time, I like to read magazine stories in other publications. And I like to play guitar.

If you could have one thing tattooed upon your brain that no one would ever forget about you, what would it be?

That I actually really care about my job. I care about Wired because I think it’s really important for society to have these conversations about technology, such as free speech and technology. And I feel like Wired plays a really important civic role. So, I want them to realize that what excites me about this job and what I do isn’t just because it’s a cool job and I work in media. It’s because there’s real civic value in having this thing work and to do it well. And that’s why I try.

My typical last question; what keeps you up at night?

Nick Thompson: I don’t think any editor in chief of any publication sleeps well, with the business changes over the last few years. I worry a lot that we get stories right and I worry a lot about what comes next for us. What are the product, engineering and business choices we need to make to be sure that we can continue to produce really great journalism. So, that keeps me up at night.

Thank you.

More like this

The Mr. Magazine™ Interview: Print is never going to go away, says Hearst’s Joanna Coles

The Mr. Magazine™ Interview: Content is about earning people’s attention