Fighting fakes

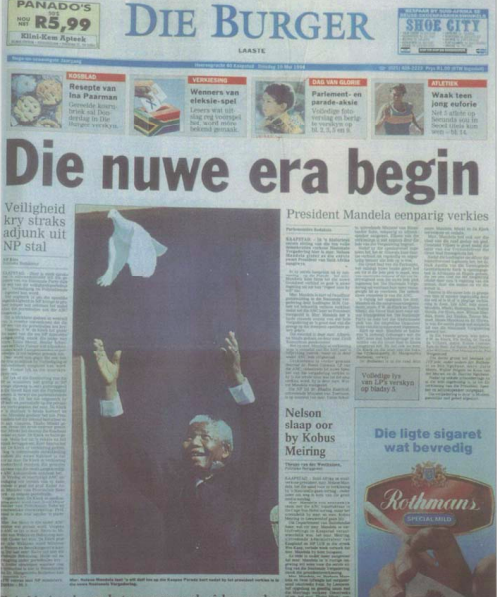

In May 9, 1994, not long after Nelson Mandela was elected the first democratic president of South Africa, Cape Town Afrikaans language daily newspaper, Die Burger meaning ‘The Citizen’, published a photograph of Mandela releasing a white dove from the balcony of Cape Town’s City Hall. The photographer, Henk Blom, was early on the shutter for his first frame, capturing Mandela with the dove still firmly in his hands, and late on the second, with the dove now at least two arm lengths above the newly elected president.

The chief sub editor at the newspaper was not amused. It was the very early days of digital photography and Photoshop, and she possessed over just about enough computer skills to lower the dove to appear half a metre from Mandela’s outstretched arms – her preferred, perfect as cover shot for the next day’s newspaper. There was a subsequent outcry from colleagues – not least Blom himself – with the affair leading to at least a dozen scholarly articles dedicated to what the correct ethical approach should be to the digital manipulation of images. Ironically the newspaper’s headline on that day read: ‘Die nuwe era begin’, meaning ‘The dawn of a new era’.

|

Fast forward 24 years and the digital manipulation of photographs is arguably lower down the list of ethical journalists’ concerns when it comes to truth, content manipulation, deception and fake news. Deepfake technology, AI-based image synthesis assisted manipulation of video content, is now at the dawn of a new era. It is being developed at an alarming and accelerating rate by employing machine learning algorithms to make any person you may possess images of, say or do virtually anything you have a video and/or audio of. In other worlds, superimpose images of one individual over another in video format or other, to look like and sound like the real deal.

Deepfake apps

More distressing is the fact that quality deepfakes can be created by anyone with access to source materials, open-source code and an app to assist them. It no longer requires knowledge of deep learning algorithms. One of these apps, FakeApp, has been downloaded more than 100,000 times between its launch in January and the end of June this year, according to its developer.

While it is true that the overwhelming implementation of deepfake technology is to make it appear that celebrities are starring in porn videos, the potential to create fake news videos is enormous. Combine deepfake apps with a programme like Adobe’s Voco – essentially Photoshop for audio – and the possibilities grow at a terrifying rate.

Voco uses a learning algorithm to analyse speech patterns and convert it to text. With 40 minutes of one person’s voice audio the programme will have enough examples to create almost every possible sentence. To create a new audio you simply have to type what you want the person to say and deepfake technology will not only place that person’s face on a video of your choice, it will also ensure facial expressions and lip movement sync with the audio.

While those who develop and celebrate these new technologies grapple to find examples of where its application can find positive uses (having deceased actors appear in movies is one being mentioned), the negatives are obvious. In an era where the broader public already struggles to differentiate between news, propaganda and fake news, deepfake technology is a powerful weapon in the arsenal of fake news creators, regardless of motive. Add to this the multiplying effect of social media on distributing fake news, and you have the makings of a dangerously perfect storm.

Video: BuzzFeed

The content validation industry

There are those who see solutions. Kaveh Waddell, writing for axios.com, says we are about the witness a war on deepfakes. “Researchers are in a pitched battle against deepfakes…” but he admits that these researchers warn it can take “years to invent a system that can sniff out most or all of them”. For those in the battle against deepfakes (there is reference to ‘deep fake detectives’) there’s an attraction of entering into a burgeoning content validation industry.

Ryan Holmes, entrepreneur and investor, best-known for founding social media management platform, Hootsuite, recently suggested that there is a flurry of activity in the arena of combating fake news – in all of its mutations – and it could be lucrative.

Writing for medium.com, Holmes said some best examples are startups such as Truepic, supported by Reuters to the tune of US$10 million, which intends to identify inconsistencies in eye reflectivity and hair placement on videos, and Gfycat, a gif-hosting platform, which has developed AI-powered tools that check for anomalies to identify and pull down offending video clips. As these technologies develop, they might become valuable assets which can be monetised.

But the content validation industry is not only in its infancy, it is also in a race to catch up with the technology that creates fake content. In the words of Prof. Ira Kemelmacher-Shlizerman, a specialist in computer graphics, augmented reality and virtual reality at the University of Washington: “(Only) once you know how to create something, you know how to reverse engineer it.”

Even before deepfake technology came onto the scene, fake news busters have been fighting an uphill battle. And it is hardly surprising. Between digitally manipulating photos a quarter of a century ago and deepfake videos emerging this year, lies a universe of manipulated content across vast platforms in various manifestations. To take it on, many have tried – and failed. Even Facebook, with its vast resources cannot begin to scrape the bottom of the barrel in its efforts to vet content. Anti-fake news agencies across the globe write reams of ethical codes, verification handbooks and form partnerships devoted to verification processes, but have seen little success.

See you in Vegas?The next FIPP World Media Congress takes places from 12-14 November 2019 in Las Vegas. Book by 31 October 2018 to get an unbeatable discount (plus, FIPP members get free hotel): fippcongress.com |

Trust in information and journalism

Alex Champandard, an AI researcher and co-founder of an agency that delivers AI solutions to creative studios, Creative.ai, warns that everyone should be aware of how easy and fast content can be corrupted if technology is exploited. Yet, he says, the problem is not technical advances per se, nor should the emphasis be on technology to solve it. Publishers should rather rely on trust in information and good journalism. “The primary pitfall is that humanity could fall into an age in which it can no longer be determined whether the depicted media corresponds to the truth,” says Champandard

His assumption is that in a world where seeing is no longer believing, publishers only have one ally left – the trust they have earned with their audience.

In fact, several recent studies have indicated that fake news has elevated people’s trust in traditional media and legacy publishers. It boils down to one simple solution: if publishers cannot convince audiences that the videos on their platforms are authentic through technology, they need to depend on the trusted reputation of their brands.

With this principle applied to all content, at all times and in all circumstances, maybe Die Burger should never have lowered that dove in the first place.

More like this

Chart of the week: Trust in platforms vs journalism

Can platforms ever be trusted in an ‘attention economy’?

Chart of the week: The EU’s most trusted news sources

[Video] Juan Señor: Reader revenue, not new technology, will be the salvation of journalism

The New European, GQ, and Inside Housing on building trust in an age of fake news