Minting an icon

This year, iconic men’s brand Esquire is celebrating its 90th anniversary. Editor-in-Chief Michael Sebastian explains how they’re embracing the possibilities of digital, while staying true to the brand’s print legacy.

It would be very easy for a brand, when celebrating its 90th year, to embrace nostalgia – but Esquire is setting its sights firmly on its future. “As an iconic, heritage brand, a lot of great stuff has come before us, but we’ve always felt that Esquire is at its best when covering what’s happening right now, and what might happen in the years to come,” says Editor-in-Chief Michael Sebastian. “We are celebrating with a big editorial package for both digital and print called ‘The Next 90’, the idea of which is to look at the 90 people and ideas that are defining the future.”

That said, they couldn’t let the celebrations pass without acknowledging what is often referred to as the ‘greatest magazine story ever written’ – Gay Talese’s ‘Frank Sinatra Has a Cold’, published in 1965 – and have made a short documentary about the writing of that article, due to be published in late November 2023. “Earlier this year, our video team spent a lot of time interviewing Gay Talese, who is now 91 years old, in his apartment on the Upper East Side of Manhattan,” says Michael. “It’s very cool to hear his own telling of how all of this happened, stories from behind the scenes. He shared his notes with us, as well as some of the other ephemera that he has kept all those years. It’s incredible.”

How does it feel being the editor-in-chief for a milestone issue of a brand with such a powerful legacy? “Overwhelming, mostly in a good way!” he says. “The founding editors wrote in the first issue that people should think of it as a starting point, that every issue after this was going to get better. But for the first 30 or so issues of Esquire, we were publishing Ernest Hemingway and F Scott Fitzgerald, and later James Baldwin, and Nora Ephron. What a bar to set!” This bar, while high, is something the team try to cross every time they publish. “That means continuing to produce an incredible print magazine, of course, but we also have the benefit of publishing on a website and on social media channels every day,” he says. “I hope tomorrow is a better day for Esquire than today, and the day after is better still.”

Part of the evolution of the Esquire brand has been reassessing the idea of who an ‘Esquire guy’ is, and one of Michael’s aims has been to expand and democratise this concept. “Esquire’s DNA has always been solid – we elevate the lives of our readers, whether that’s what’s in their closet, or where they eat, or where they travel, or how they make sense of the world. But when I became editor-in-chief, I did think that the brand had gotten just a little dusty,” he says. “If you asked people, ‘Who’s an Esquire guy?’ they would have said an older guy who likes dens, leather chairs, and brown liquor – not that there’s anything wrong with that! But I think the Esquire man is a guy who’s evolving, who is curious about the world. Our message now is more, ‘let’s go on this journey together, guys’.”

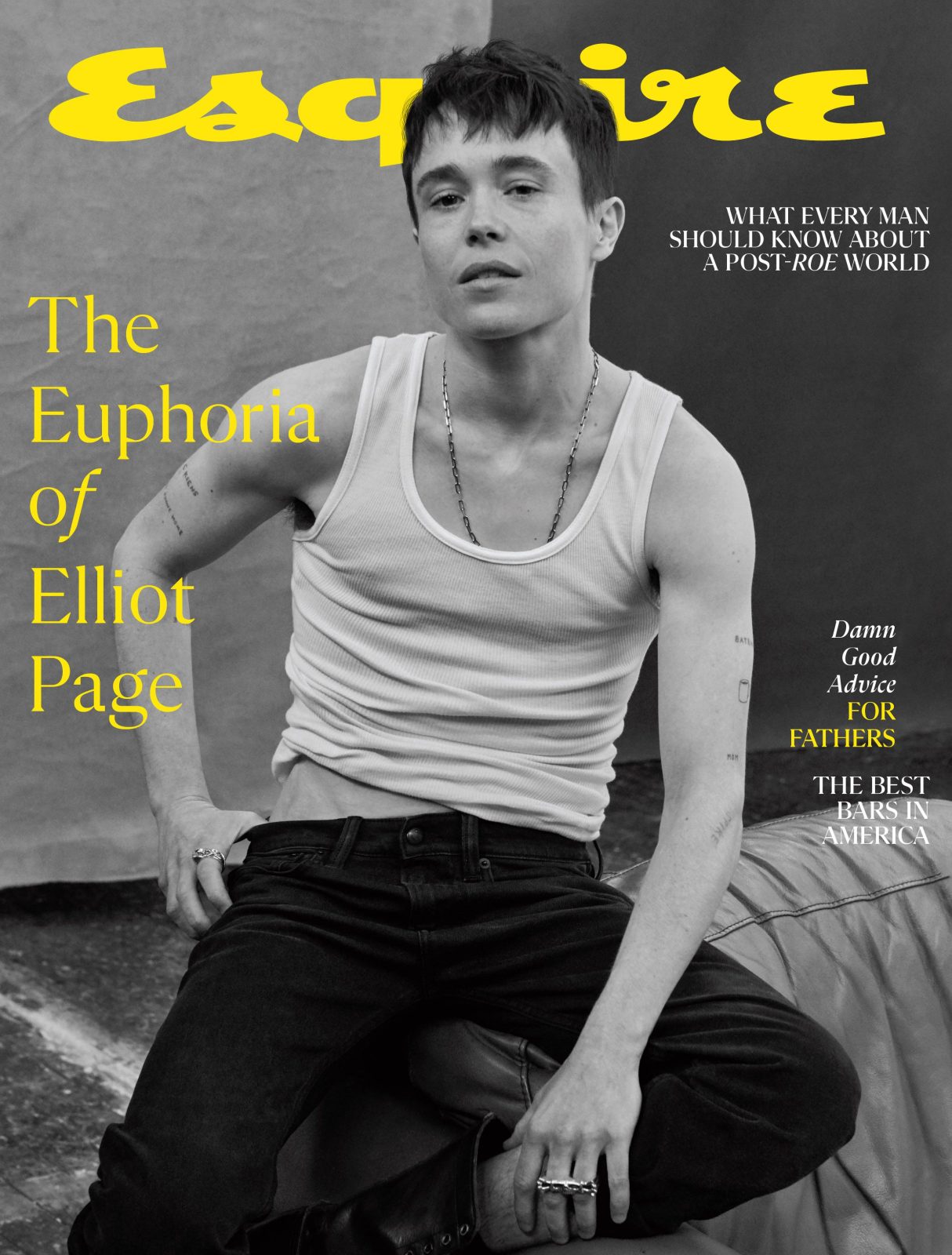

This repositioning has included consideration as to who they put on the cover, who they feature online and in print, and who works on the magazine. Significant strides were made when they put Elliot Page, a transgender man on the cover – the first major men’s magazine to do so – which received backlash from some quarters, but also resonated deeply with some loyal readers. “I got a tweet from a father in Texas who said, ‘I’ve been a subscriber to Esquire my entire adult life. I have a son who’s transgender. And it’s so great to see my magazine (as he phrased it) putting Elliott Page on the cover’.”

The founding editors, I point out, said that they wanted Esquire magazine to be “all things to all men”. Is this possible, or even desirable? “Of course I hope all men want to read Esquire, but I also know that the media has diversified in in countless ways, and by trying to appeal to everyone, you end up appealing to no one,” Michael says. “Unless you have the budgets and the staff of the New York Times, you’re doing yourself a disservice by trying to be a generalist publication. For us, that boils down to good taste, and good editorial judgement, so that when we publish a story, it has a point of view that makes guys want to come along on the ride with us.”

Esquire covers are iconic, particularly examples from the 1960s, when George Lois was the design director – think a Saint Sebastian-esque Muhammad Ali, or Andy Warhol in a tin of Campbell’s soup – but they too have evolved over the decades. To try and replicate that, Michael says, would be ‘a trap’ for any present-day editor of the magazine. “When I first started, my creative director, Nick Sullivan, pointed out that the editors of the 1960s weren’t looking to the 1930s for inspiration, they were looking to the current moment – and that’s something I’ve always taken to heart,” he says. In the 2020s, that means appealing to our ‘celebrity-obsessed’ culture by putting celebrities on the cover. But, he says, it has deeper significance.

“It’s important – and this is something I wanted to do from the moment I started – that we capture them in a way that they really haven’t been viewed before, whether it’s the clothes that they’re wearing, the pose they’re striking, or the setting that they’re in,” he says. “But I also like to ‘mint’ icons, so take a celebrity who you’ve seen a zillion times, and then depict him in a such a way that when you see him on the Esquire cover, you know he’s reached a certain point in his career – he’s now an icon”. This philosophy also extends to the editorial. “I set a very high bar for the writer and editor: each feature has to be the definitive story about this person, so we need to open a new chapter in their life, we need to portray them in a way they’ve never been portrayed before. That requires access, it requires time, it requires great writing, and it requires superb editing. Those things will never not be essential to us.”

And as for the future of Esquire… Michael is determined that when he hands the brand over to the next generation of editors, it is stronger than when he took over, something which relies on being true to the brand DNA of “great storytelling and great taste”. “I want to make sure that those underpinnings are intact, that whoever takes over knows that it’s a crucial part of what we do. I don’t want to betray that part of our heritage.”

For future readers, this will mean reaching them on the channels they want to be reached on. “I want to make sure that we are creating a product so good, that the young men and women who are currently in their late teens and 20s come to love it and read it for the rest of their lives – and that boils down to how we get in front of them.” Continuing to evolve and adapt, he believes, is key to this success. “It used to mean sending out a magazine, but they don’t read magazines, so it’s about how we market the brand, how we evolve this once print-only, 90-year-old brand into areas that are both obvious – like social media – and unexpected. Not only do we want to stay on top of and ahead of the trends, but we also want to stay on top of how audiences interact with Esquire.”

Adapting to the demands of future generations doesn’t mean devoting less energy to the print magazine, however. Although it is now only published six times a year, it remains, Michael says, essential to the Esquire brand. “I look at our print magazine as the flagship store on Fifth Avenue – if digital is the beating heart of the brand, then print is its soul.” Importantly, he says, it still carries significant cachet with the people who feature within its pages. “From a purely tactical point of view, having a print magazine is one of the reasons we’re able to book A-list celebrities, or get the A-plus writers or photographers. Even influencers whose celebrity was minted on social media desire the credibility that Esquire grants them – we still have a place in the world that means if we feature you, that’s going to be a big moment in your career.”

Michael came on board as Digital Director of Esquire in 2017 and became Editor-in-Chief two years later. He says his experience of the print-digital divide has been an interesting one. “I came in wanting to create a magazine that felt like the internet, but I realised about a year in how foolish that was. The internet exists for a reason; we don’t create a website that feels like print, so we shouldn’t create a print magazine that feels like the internet.” He firmly believes, however, that there is important crossover between the two, despite each appealing to a different audience. “The thing that crosses that print-digital divide is that all Esquire audiences – regardless of whether it’s print, digital, video or in person – love a great story and great photography, and these always perform well on both platforms,” he says. “There’s no denying that the present and future of this brand is everything that we do online and in the real world. That’s where the brand is going. But as far as I’m concerned, print always has a place. We’re making a product that can transcend the platform it’s on.”