Publisher business models in the age of platforms

This is according to Greg Piechota, research associate at Harvard Business School and 2016 Nieman Fellow, who recently shared his thoughts in the Future Media Lab session at the Digital Innovators’ Summit in Berlin. Delegates at DIS rated Greg’s as one of the top sessions at DIS 2017.

Read an edited version of his talk below, or if you prefer, watch the video here instead. Greg’s DIS presentation slides are also available to download, here.

Meeting Google’s ‘toothbrush test’

Greg started off by asking whether the DIS audience has heard of Google’s toothbrush test. He explained legend in Silicon Valley has it that when Google considers investing in a company, the question is whether people will use their product/service several times a day – like a toothbrush. “Obviously news content passes the toothbrush test. Our content is driving daily news consumption and engagement on platforms all over the world.”

All publishers are now in niche media

Almost half of US adults are using Facebook for news. Platforms are therefore the mass media of today, with no publisher near the size of the main platforms. “We are no longer in mass media business, we are in niche media business. And it has a profound impact on our strategy,” Greg explained.

Can platforms, advertising sustain journalism?

“Because platforms have aggregated such large audiences, they win at the attention economy [the battle for user attention]. They then capture most advertising in the market, with – in the US – Google and Facebook’s share last year up to 70 per cent… So publishers are now fighting for 30 per cent. And who is getting the money?… 60 per cent of the money goes to AdTech companies… In fact, publishers get one-third of the revenue.”

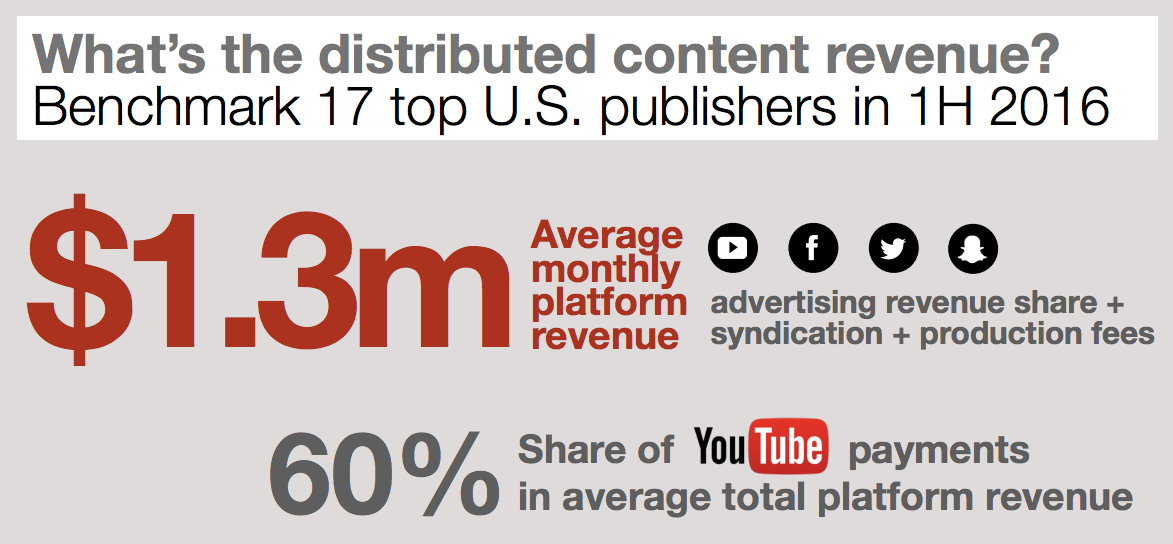

That leads to the question whether publishers can get more money from platforms if digital advertising is not substantive enough. However, according to a benchmark study in the US, the top 17 US publishers received monthly revenue of average US$1.3 million per month from platforms, said Greg.

“The cost [base] of The New York Times per year is something like US$1 billion. This is not going to pay for [it’s journalism]. This is not going to sustain it. So even if we imagine that we push the platforms, and we should push them, to get us a better deal… Even if we get Mark Zuckerberg to share all the money he gets from advertising… There are like 50 million publishers on the FB platform, so what do we get per year? 500 bucks?”

Contrast this against the past, Greg said, where display and/or classified advertising were the bedrocks of newspaper and magazine revenues. This leads to the “big question”.

Given above examples, “Is [revenue from platforms] going to pay for our content? Is it realistic to expect that digital advertising, in the way it is evolving today, will pay for our content? So who is going to pay? This is the big question.”

In moving towards an answer, Greg went on to discuss three waves of disruption.

*** Get more stories like these delivered to your inbox. Subscribe to our weekly FIPP World newsletter.

First wave of disruption

The first wave of disruption was the unbundling of media products into a variety of verticals. For example, purely unbundling newspaper content and classified marketplaces “basically crushed newspaper revenues”.

The unbundling continues to today, not only verticals but also individual articles. “So you get headlines of articles in aggregators, you get visual elements on social platforms. Comments and reactions [to stories] go to external platforms. Recommended stories are often not recommended to us by publishers anymore, but by social media.”

The result of this is that some of the biggest publishers in the US are now publishing on upwards of 20 platforms (see the latest chart from the Tow Centre, Columbia Graduate School of Journalism here).

Second wave of disruption

The second wave of disruption is disintermediation. “Basically, we were the gatekeepers. If someone wanted to reach the market, they had to go through publishers…” Today, anyone can be a publisher, attracting large audiences.

Third wave of disruption

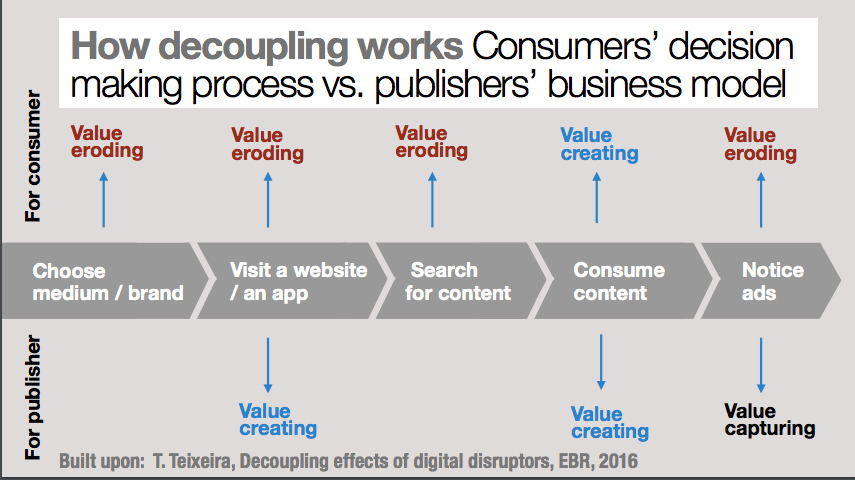

The third wave is decoupling. This refers to the consumer decision-making process versus publishers’ business model:

For consumers, having to choose the medium and brand, sites or apps to visit and searching for content they want and then being forced to watch ads are all value eroding activities (in terms of e.g. time, effort and cost). In contrast, publishers created value through their brand websites and content; then capturing the value through the ads they served.

In turn, Greg said, platforms (and others such as ad blockers) are decoupling the act of consuming content from the act of value creation for publishers (and others, such as TV and “all kinds of other media”).

“People don’t love watching ads. People don’t want to spend a lot of time on choosing the brand and looking for stories. If somebody can save them the effort, if somebody can save them money, save them time, people go for it…”

What is the strategic response to this?

First Greg listed a number of assumptions:

1. Digital is the future for content consumption.

2. Platforms are not going away (… “They have a much more superior business model [than publishers’] current business model”).

3. Consumers are not going to start loving display advertising.

One strategic response would be charging other parties for content because “what has been decoupled is the consumption of content from capturing value from this content. What if we make it impossible to decouple it, because the content itself will be paid for by somebody?”

Using The New York Times as example, Greg listed a number of parties paying for their content:

• Consumers (direct subscribers)

• Native advertisers

• Affiliate marketing (retail clients, through the acquisition of e.g. The Wirecutter and Chef’d)

• Donations (e.g. buy a subscription for a student)

According to Greg’s estimations, this translated into the following revenues:

Combined, this is more than The Times gets from Facebook, Greg said.

The need for business model innovation

Several companies have changed their business models in the past decade. “It’s not only [because of] technology. The airline industry that I’m studying was basically losing money for the first 120 years until someone realised transportation wasn’t really going to make money…

“So Ryanair, one of the innovators in this field, started to charge for everything… for your seat, for checking in a bag, for paying by credit card; and then you can buy insurance, book a hotel, rent a car, whatever. All these adjacencies make Ryanair profitable – last year Ryanair made more than €1 billion profit, at the same time they lost more than €100 million on [the] travel [component].”

When publishers think of changing their business model, Greg said, perhaps “we should think about content portfolios, [i.e.] different content with different business models…

“We will have news content for example that will not be profitable any time, but it is important because it attracts users… At the same time we’ll have other types of content, paid by different parties that will help us finance the whole thing.

“Of course, when we think about what kind of content we’ll have, we’ll optimise for different functions. We’ll have some content that will attract new users… we’ll have some content maybe to retain customers. As you heard several times during this conference [DIS], people who are subscribers have different needs from those who only come as visitors to your site… And then we’ll have some content used for [upselling]. In this way, you will increase the [Average] Revenue per User (ARPU) from the audience you have.”

Doing this changes the operational context for publishers, Greg said.

*** Join FIPP for our next event: the iconic FIPP World Congress, taking place from 9-11 October 2017 in London. Discounted pre-agenda bookings are available until 30 April, with savings of £800 or more on eventual rates.

Platforms as ‘suppliers’

“You are no longer competing directly with platforms; you are rather thinking about platforms as your marketing tools. They are big fishing ponds for your customers. This is [also] the place where you expand reach of your branded content campaign.

“You think about them as your suppliers rather than your business partners. You are not begging them for money; you are basically ‘hiring’ them to do a job for you.”

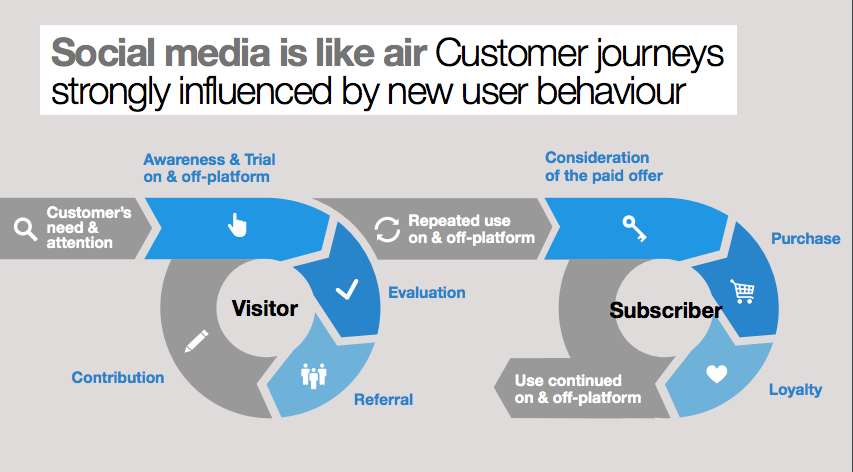

Greg illustrated how social media have changed the consumer journey and what in means for publishers. It includes users consuming publisher content, interacting with it (e.g. likes or comments) and/or sharing it, all the time without knowing the brand behind the content.

Moreover, today, even after consumers become repeat users, or subscribers, they may still prefer to engage with your content via a platform, rather than your website. “It is possible that your subscriber will still use Facebook as an entry point to your content,” Greg said.

But whereas most publishers currently look towards platforms to build reach, engagement with their content and traffic to their websites, Greg argued that this is a reflection of the traditional publisher model. “If we can get traffic cheaper from Facebook than we charge for advertising on our sites, it makes sense…” However, publishers should instead be looking at customer acquisition opportunities platforms allow them, i.e. to make customers out of users.

If content is good enough, the business model has to be the focus

There are many risks associated with platforms, from changing algorithms, to changing the rules to changing margins. However, platforms also supress branding where, with their “non-differentiated layouts”, where the general user cannot tell the difference between a story from for example the Washington Post from that shared by a fake news site. “We need to talk to platforms … about [differentiating] our offering on platforms, so we can segment users easier, only attract users we want to attract…”

However, perhaps publishers are putting too much focus on content itself, Greg said. “Maybe our content is fine, maybe we put too much focus on improving the content itself…

“Maybe it’s the business model that we rather need to fix… Maybe we should forget about chasing reach … [millions of users] that we cannot monetise… And we should rather focus on the audiences we have, and how we grow the average revenue [ARPU] from this audience.”

A final word: stop the frenemy talk

“And maybe should stop discussing whether platforms are your friends or enemies… Maybe we should rather change our perspective, and ‘hire’ them to work for us.”

[News update: earlier this week, Digiday wrote that several publishers appear to be cooling on FB Instant Articles, including The New York Times, in part because monetisation is better when referring users to their own sites than in Instant Articles. Facebook on the other hand announced a number of new tools for publishers, including enabling more direct Calls-to-action features with which to capture and monetise users. ICYMI: Also read ‘The Platform Press: How Silicon Valley reengineered journalism’ by Emily Bell and Taylor Owen for the Columbia Journalism Review]