[Long read] How to get into VR and 360º videos

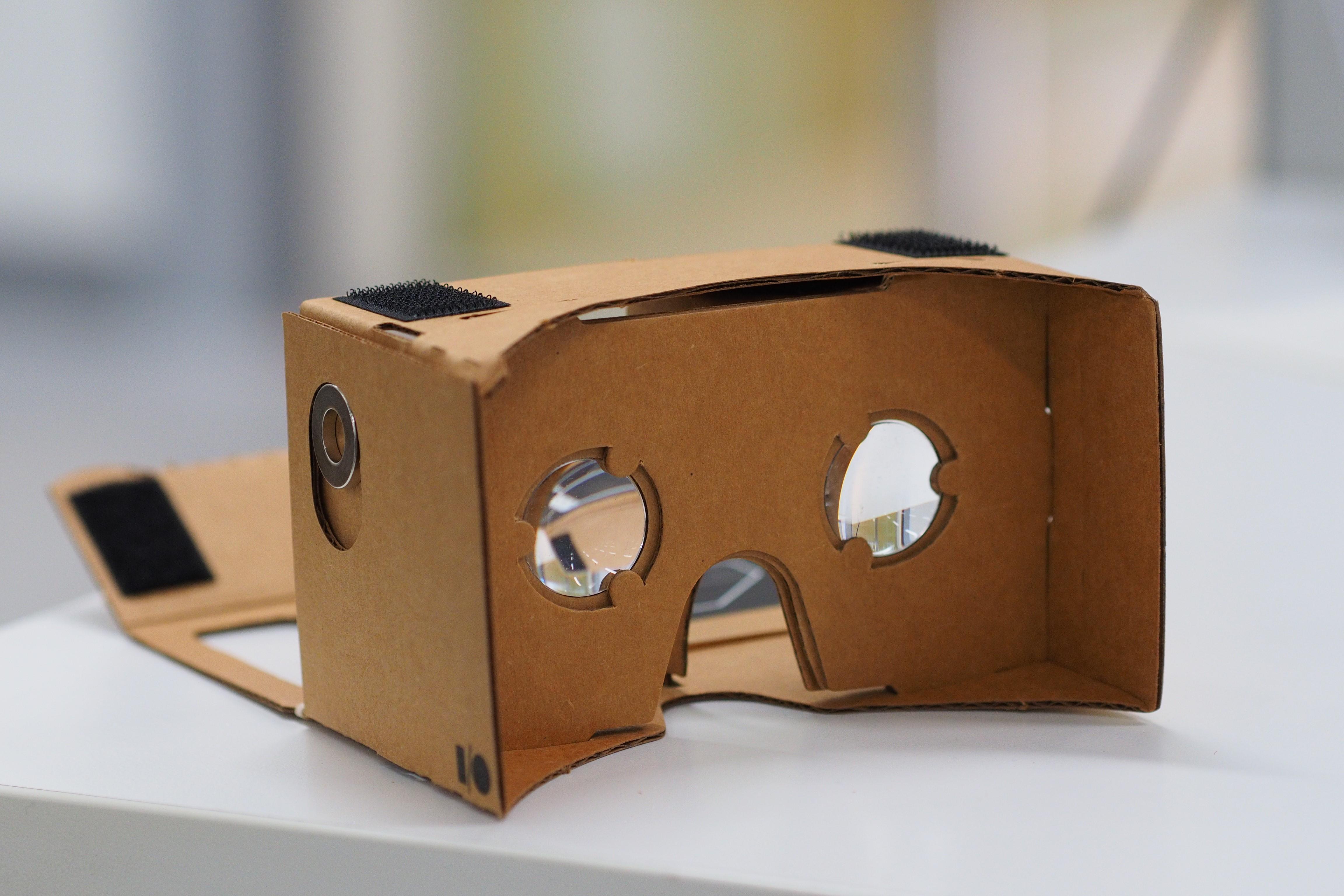

Then in 2015 The New York Times partnered up with Google and sent Google Cardboard virtual reality headset to 1.3 million of The New York Times’ Sunday print edition subscribers. “The Displaced,” virtual reality film about children uprooted by war, became an overnight success and went on to win multiple awards, including Lions Entertainment Grand Prix last year.

You can also download this article as a PDF.

Just in two years, it has become clear that virtual reality is so much bigger than games. HRB reports, VR and AR (augmented reality) are emerging technologies, but startups in this sector raised $658 million in equity financing last year. If you are reading this report, it means that you probably want to jump on the bandwagon.

AR vs. VR vs. 360-degree video

First, let’s review formats that you could use for your project. There are currently three types of production: a 360-degree video, augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR). The most popular modern-day example of an AR project is Pokemon Go, which combines digital world (the Pokemon Go app) with physical reality (getting around the city to catch Pokemons).

The difference between 360-degree video and a VR project is often blurred.

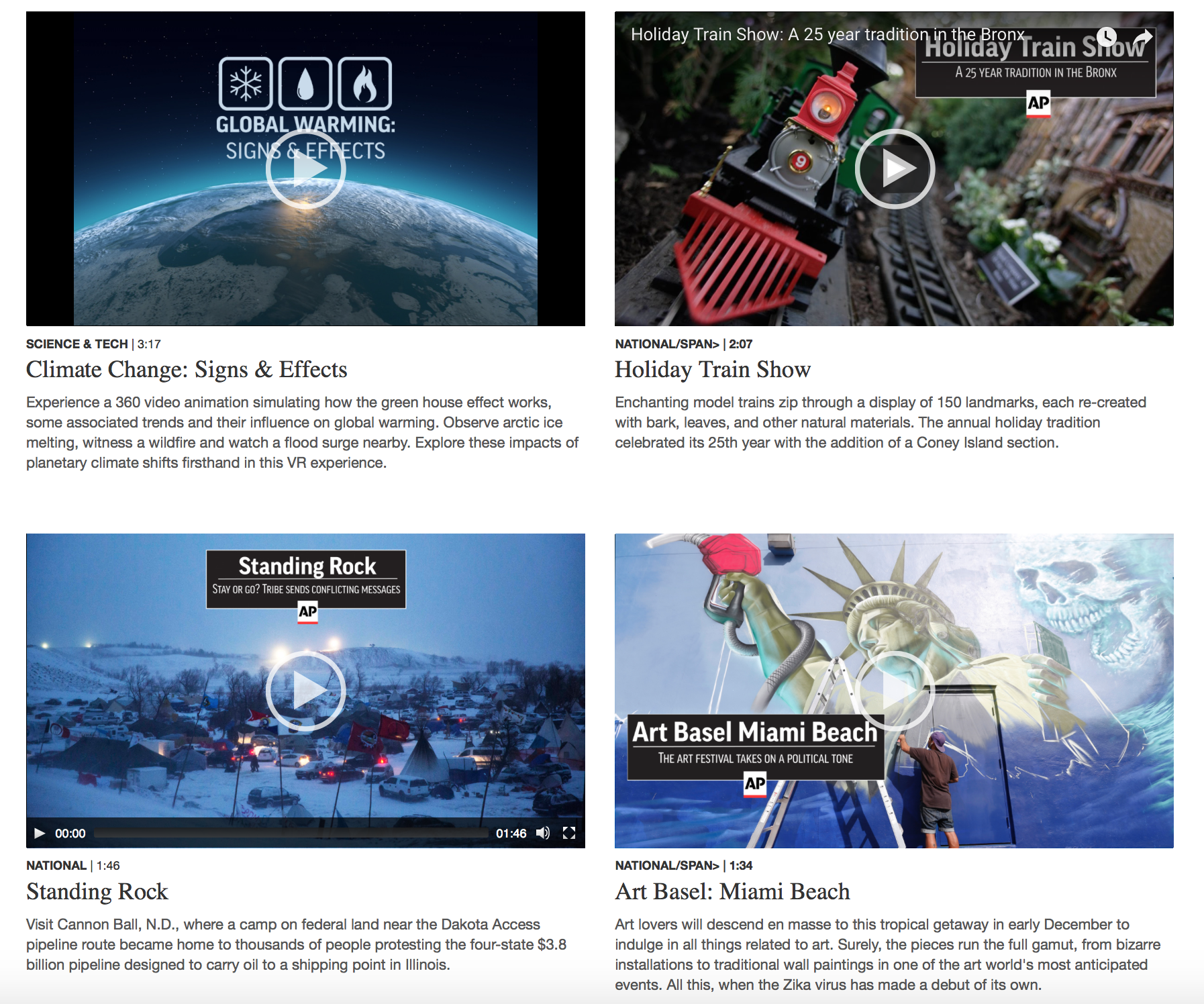

“VR with headsets is a fully immersive experience which allows a user to take part in the action and control it. 360 video is an immersive experience as well, but it can be viewed without a headset, and in 360 you are along for the ride”, says Paul Cheung, director of interactive and digital news production at AP.

Technically speaking, NY Times’ “The Displaced” is not a VR because it is not interactive. But it shows the power and potential of immersive journalism.

“The journalistic idea behind a VR project is to give readers the opportunity to experience places and situations that are otherwise out of reach. We have already been inside the police helicopter, on an oil rig, on top of Lysefjord Bridge and inside a Norwegian army tank.” – says Svein-Erik Hole, the editor of leading Norwegian technology and business magazine Tu.

In two years, both, brands and media companies produced hundreds of fantastic examples of VR films and experiences. Lockheed Martin was behind a “Bus to Mars” campaign that Advertising Age called one of the best VR projects of 2016. Group of kids took a real, not a virtual school bus ride to USA Science and Engineering Festival in Washington, DC in 2016. As they left school, the windows of their bus were transformed into a headset-free VR experience that featured a ride on Mars. Created with agencies McCann New York and Framestore, the windows screened 200 square miles of Martian surface. The system enabled the view to change and turn when the bus turned.

Expedia created a VR trip taking viewers on Europe’s steepest railway line, the Flam Railway in Norway, to celebrate the line’s 75th anniversary.

Oculus and Felix & Paul Studious take users with them as they visit the Obamas in their home of the past eight years in “The People’s House: Inside the White House with Barack and Michelle Obama.”

There are many notable VR projects from media companies. As it turned out, some stories simply would not be as engaging and immersive if they did not go along with a VR app.

National Geographic (a FIPP member) launched in-house VR studio last year and had released tens of 360-degree and VR- films, such as this gorgeous Wild Yellowstone.

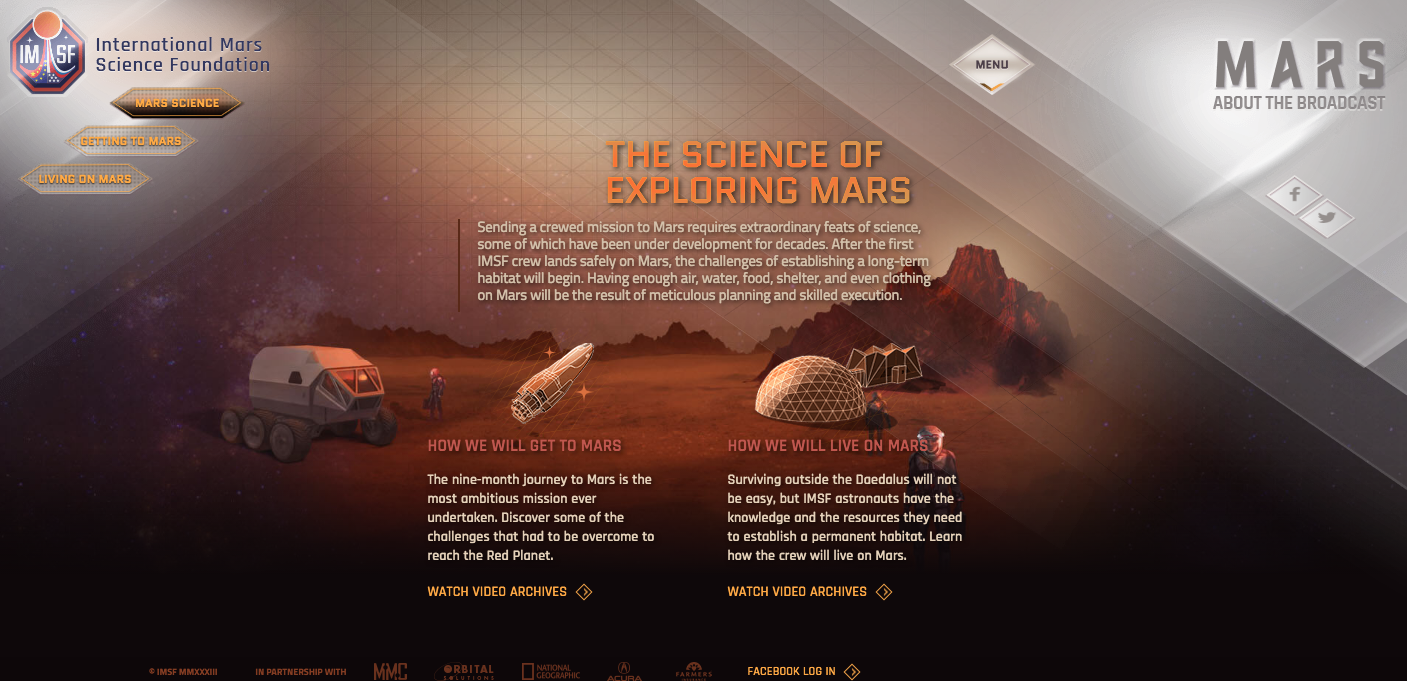

Make Mars Home is a series of five interactive in-browser VR games. The project, which is a part of a campaign to promote its Mars series, expands the narration in an alternate reality campaign where future colonists can try out take part in a mission to Mars using VR. This cutting-edge multimedia experience was produced by National Geographic in collaboration with digital creative boutique Neo-Pangea.

“With Make Mars Home, National Geographic wanted to extend the reality of the series,” – says Neo-Pangea’s creative director and partner Brett Bagenstose. “It would actually be easier to make an app for Oculus, but we would significantly limit our audience. Instead, we produced in-browser experience everyone can enjoy.”

Norwegian Tu has produced more than 15 editorial films.

“Tu Media is a small organisation with 70 employees, – says Svein-Erik Hole. Our multimedia manager Eirik Helland Urke is a pioneer within visual storytelling, and he’s the brain, the heart and the soul of our bet on VR. He’s the only one ‘behind the camera,’ working in collaboration with our niche journalists. All our writers are exploring VR. Whenever someone leaves the office to report on a news story, they bring along a VR camera. Our goal is to make everyone able to handle VR, and use it when it adds value to their story”.

The New York Times has a VR section and a dedicated VR team, but it also works with independent production companies. So does The Guardian. They released their first VR film, “Underworld,” in November 2016. It was produced by in-house VR team and creative content studio The Mill.

Launching your first in-house VR team step-by-step

Svein-Erik Hole of tu.no says that starting a VR section on the website in 2015 was a conscious corporate decision. Two years later, the company received 300.000 euros from Google’s Digital News Initiative Fund which gave the editors the ability to explore the format at a comfortable speed.

“One of the project goals was to create a new revenue stream, which we have achieved,” says Svein-Erik. “VR stories within content marketing category is now an important ad format for us.”

AP launched a dedicated AP-VR360 section last year. According to Paul Cheung, the company focuses on scaling up their expertise in 360 storytelling and experimenting with web VR. They are also exploring if 360 content can become a separate subscription revenue stream.

Before jumping into AR, VR and 360, ask yourselves the following questions. Who is my audience? How big is my story? Is the story supporting the journalism that I am producing, or it could live separately, like NY Times’s meditation series or National Geographic’s Mars? Are AR/ VR and 360-degree video the most effective ways to tell the story? Which format to favour?

Even though there are quite a few companies involved in VR game – Oculus, HTC/Valve, VReal, Microsoft, Endeavor One, Pluto VR, Pixvana, VRStudios – we could not find estimates of the total amount of headsets sold to date. At CES 2017 Samsung reported the company had sold 5 million units of the Samsung Gear VR globally and that users have already watched over 10 million hours of 360-degree video clips using the Samsung Gear VR.

Tu, Financial Times, The New York Times and some other companies distribute Google Cardboards to readers at events, professional conferences and trade shows and encourage them to try VR experience.

Oculus Headset costs around $500 and can be operated only with a specific software and a computer. Samsung VR Headset costs around $100 plus the price of a compatible Samsung smartphone, and it is still powered by Oculus VR technology. According to Yahoo Finance, the most successful headsets have been Samsung’s Gear VR and Google’s Cardboard, which costs $15 in addition to the expense of a smartphone.

Therefore, choosing to go with an authentic VR project with significantly limit your audience but will create a much better and more memorable user experience.

Now, what’s your budget and what’s your timeline? Who is with you on the team? The cost of a professional equipment is still high. According to CNET, the Nokia Ozo Camera, which is used by many professional VR studios, will cost you a little more than $50K. Even though this particular camera stitches the video together, post production is a whole different story.

“There is no getting around how expensive the technology is, and how time-consuming production and post production are,” says Brett Bagenstose of Neo-Pangea. “Make Mars Home took National Geographic and Neo-Pangea one year to produce in its entirety, and the VR portion took around six months”.

But both, Paul Cheung of the AP, and Svein-Erik Hole of Tu argue that initial investments don’t need to be high. Consumer grade 360 cameras such as Samsung Gear and Nikon Key Mission, does the job well and only cost a few hundred dollars.

Svein-Erik Hole says “You get a camera, you learn the basics within a day, and then just jump into it and try. I believe in adding basic VR skills to every journalist’s tool box”.

If you have graphics, how do you incorporate them into virtual space? How do you lead people to a focus since they will be looking around during the entire narration? An excellent example of using 360-degree footage and motion graphics but still keeping your attention in check is The Verge’s VR interview with Michelle Obama.

“360 video is not just a luxury accessory to storytelling. We are creating a lot of enthusiasm by showing that anyone can do it as part of their regular assignment,” says Paul Cheung. “Based on the camera you have, send one-two-three people to the shoot. Prepare beforehand the shot list, and the narrative story. Remember that most of the world is not set up for 360 experience, so you have to have a focal point and a plan. It is crucial to find a reason for a viewer to turn, so shoot more dynamic scenes.”

The more you know ahead of time, the better. Scouting trips are important because they will give you the idea about the lighting and the sound quality.

“You can always scale the project to fit a Disney picture, and then you may want to hire a production company,” says Svein-Erik Hole. “But for journalistic needs, it is possible to handle costs efficiently. To demonstrate the low-key opportunities, Eirik Helland Urke made a one-man-one-day production of a music video for the Norwegian band The Dogs. It’s as good as anything.”

Svein-Erik Hole says that tu.no is fascinated by the prospects and possibilities of authentic VR but admits that the company is not there yet.

For a true VR project where a viewer can participate and control narration, Brett Bagenstose says media companies should wait a year, but hopefully less, and see where the technology settles. Besides high production costs and no standardisation of formats, there are still too many unanswered questions, including the ethics of VR journalism and such side-effect as nausea.

How to measure the success of a VR and 360-degree video project?

It is safe to say that a VR project will bring your company publicity. Investing in a VR team will elevate your brand equity to the next level. VR is a new trend in technology and media, and the whole world pays close attention to what has been released in this field.

All editors agree that VR stories have a long shelf life and they bring long tail traffic from search. If your project is superb, it will bring you awards and recognition. If you produce a few excellent projects, they will bring you new readers and paid subscriptions.

A more straightforward mathematical approach to measuring the success of a VR story is the amount of visits, views and time spent on page. Svein-Erik Hole says that their VR stories have a similar audience size to regular video stories. “The traffic value for rich formats like this is longer view time, higher social engagement, and more incoming links which are good for SEO.”

For now, there are no tools that allow measuring headsets views vs flat 360-degree views on desktop or mobile.

The next big thing?

Tim Sweeney, American game programmer and developer, says in an interview with Glixel that over the next 12 years VR will scale down from a helmet to a device the size of sunglasses.

“People who can just barely afford a smartphone today in Africa or the Middle East will be able to buy glasses and have a better entertainment experience than you can buy today for any price.”

Wired argues that before VR and AR “can really hit it big, someone has to build the best cameras, make the best content, find the best ways for people to consume that content, and work out a way to monetise the whole shebang.”

Imagine showing your parents and your grandma your latest trip to Southeast Asia through the VR device. Imagine showing them the magnificent mountains of Ha Long Bay in Vietnam through your eyes, and with your commentary? It would be quite emotional. Now, imagine what VR could do for journalism by taking the readers to Syria, or to Antarctica to see the shrinking ice – or better – to Siberia for the wildfires season.

Resources if you want to get into VR:

For education:

- Ready Player One: a must-read book that started the modern-day VR craze

- An interview with “Ready Player One” author Ernest Cline

- VR Ethics discussion

- How AP trains its journalists to shoot in 360

- The Guardian: The complete guide to virtual reality – everything you need to get started

- Net Geo’s announces plans to launch VR Studio

- Google Expedition training modules

- 5 VR companies in NYC that you need to know about

- VR and gaming Industry: Tim Sweeney interview

- SXSW AR/VR track

For beautiful examples and inspiration:

- Henry, a Oculus VR experience

- The Guardian VR section

- The New York Times Daily 360

- VR Library from Google

- Production Studio Here Be Dragons

- StoryUP, VR native media company

More like this

The New York Times’ VR experimentation is making money

How Virtual Reality allows anyone in the world to immerse themselves in the Clinton/Trump race

The Guardian announces virtual reality project team

Lessons from The New York Times on virtual reality

FIPP’s guide to live video in 2017

How The Washington Post drives innovation

Donald Trump’s inauguration – and why it provides us with a glimpse of tomorrow’s media