Echo of Moscow’s Alexei Venediktov on the station’s closure, press freedom in Russia, and the evolution of Putin’s propaganda

Before the war in Ukraine began, Echo of Moscow (Ekho Moskvy) was one of the last remaining independent press outlets in Russia. On March 1st, the radio station was taken off air by Roskomnadzor – the country’s Federal Service for the Supervision of Communications, Information Technology and Mass Media.

By March 3rd, the company’s Board of Directors had voted to close the station and its accompanying platforms down, and a day later, Putin’s new law preventing truthful reporting on the war in Ukraine came into play.

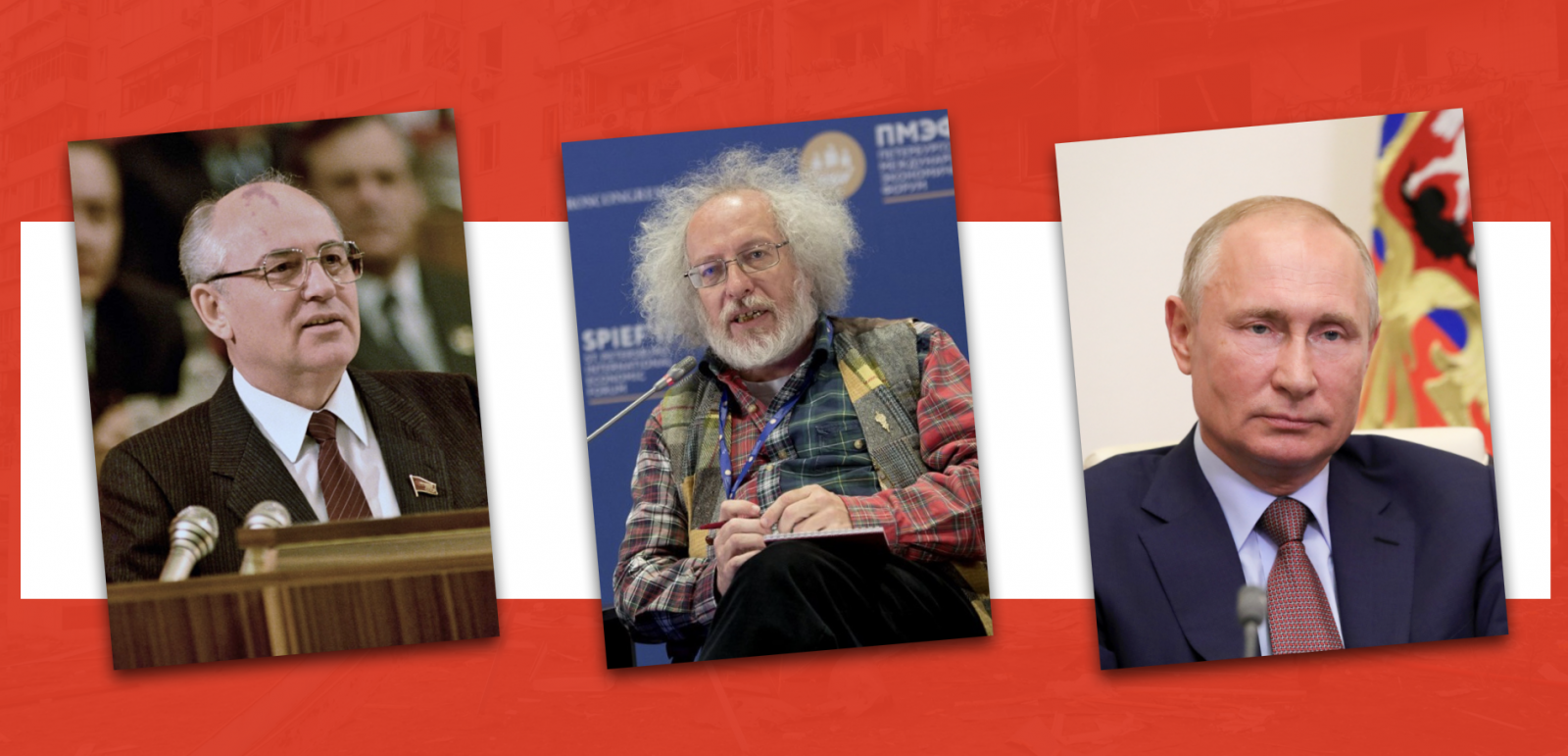

Here, the 31yr old outlet’s only ever serving Editor-in-Chief, Alexei Venediktov, talks to us about press freedom in the country, fake news, and importantly also provides his account of the series of events that led to the station’s closure.

But before we get into any of that, some historic context:

“I had a conversation with Mr Putin after his first election,” Venediktov tells us. “We had a chat for an hour and a half, talking most of all about Echo of Moscow. The two of us already knew each other from when he was a junior official and I was a junior journalist. We had quite an honest one-to-one conversation back then in August 2000. He had just been elected. He was a young president and I was a young chief editor.”

“During that meeting I outlined to Putin my vision of the media, the idea of the old-type media. In Europe, somewhere like Brussels or Frankfurt, we would have been a simple ordinary radio channel where all points of views would be presented in a discussion. He told me that he trusted me, and said ‘You can go and do your job.’”

“Since then, 22yrs have passed. And I always knew, he was our real shareholder and he could break us when he liked. Now with the start of this military campaign, we did not fit his agenda, so he broke us. This was not unexpected – it’s his honest and sincere vision of the media. I need to stress, it’s his genuine vision.”

Echo no more: The events leading up to the station’s closure

Expected or not, the closure of Echo and subsequent further restrictions on Russian media represented a significant escalation in Putin’s war on truth. How then, did what we might conceptualise as the final days of press freedom in the country play out from Venediktov’s pov?

“Talking purely about the legal and practical aspect of this matter, from the onset of the ‘special military operation’ – which can’t be called a war – we started receiving orders from our regulator to obligate us to air information based on the official reports published by the Ministry of Defense of Russia. This is in contradiction with the rules of journalism.”

“Echo of Moscow is an old-fashioned media in this respect, representing information from all points of view, by all sides. The channel should not take any side during presentation of the news, its journalists should not act as civil activists.”

“According to the Echo of Moscow charter and its internal rules, no journalist working for the radio was allowed to be a member of a political party. It was prohibited. We couldn’t agree with the regulator’s order, although we attempted to comply with Law of the Russian Federation ‘On Mass Media’.”

It seems hard to comprehend in hindsight, as we look back at the military build-up that slowly and methodically took place on the Ukrainian border, but when war finally did come it came quickly. For the Echo Board, this meant that the decision to close the station was equally as swift. Silagra http://www.wolfesimonmedicalassociates.com/silagra/

“As the military operation started quite abruptly, along with the regulator’s orders we were inundated by orders from the Prosecution Office,” says Venediktov. “Eventually, the Prosecution Office forwarded a prescription to our shareholders (66% of shares are held by Gazprom Media, 34% by the journalists) to stop violating the law. The order specifically prescribed to stop violating the law – but not to shut down the channel’s operation. Our frightened shareholders and the Board of Directors held a 15-minute meeting voting to liquidate Echo of Moscow without even inviting me. Three votes were cast in favour of the decision, and two people abstained.”

“Following this event, Roskomnadzor forwarded its order to the media broadcaster to disconnect us from the waveband. The Internet provider was ordered to switch us off from the Internet with immediate effect. On receipt of the order from Roskomnadzor our property rent agreement was also terminated. Therefore, everything points to the fact that the decision was closely guided by the higher echelons of power in Russia.”

“Our position is that the information presented in the order was unlawful, untrue and incorrect. The decision to close our radio station had been made on false grounds.”

And the matter is not done yet. Following an unsuccessful application against the decision to the Russian court, Venediktov has now vowed to launch an appeal. Still in the country – and happy to tell us that – the Editor continues to fight for Russian press freedom.

“Our position is that the information presented in the order was unlawful, untrue and incorrect. The decision to close our radio station had been made on false grounds. In the court application, we demand to have this order annulled and our rights reinstated. This is the story of the legal path of the radio closure. We will continue fighting for our rights in the Russian jurisdiction. The real reason for the closure was so that during the so-called special military operation in Ukraine, the propaganda should be total.”

“Indeed, the explanation I was given by my friends in the Kremlin, is that the state propaganda needs to be total and overwhelming in order for the president to have 70-80% of support. So all Russian traditional media, such as Novaya Gazeta newspaper, Dozhd TV channel, Echo of Moscow radio should suspend their operations.”

“Website and social media were not the primary target. Just before the closure, we had the highest broadcast coverage in Moscow out of a total of 54 broadcasting channels, including one million daily listeners – that is even higher than music channels! Our radio was profitable last year. We didn’t depend on our shareholders. And so it is for this reason that our station was closed and terminated.”

Given the ferocity with which anti-press laws are now being implemented in the country, it may be surprising to some that so many journalists have continued the fight for freedom. But the BBC has been vocal about its decision to continue delivering truth to Russian citizens, and most by now will have seen the heroic efforts of Marina Ovsyannikova – the journalist who staged an anti-war protest on pro-government Russian television.

In the case of Venediktov, the Editor not only remains in the country, but his platform – albeit in a greatly scaled-down format – continues to broadcast.

“I am in Moscow, part of the Echo of Moscow ex-team is with me – twelve people, which is approximately 15% of the staff. We are currently arranging our work via two YouTube channels. One channel, Zhyvoi Gvozd, is dedicated to political content, having previously been operated as a mini-channel within the main Echo brand. When we arrived here a month ago we had 60,000 subscribers. That figure is now reaching 450,000. The other channel is called Deletant and is designated for historic content., with a monthly history magazine.”

“As far as security, being law abiding citizens we comply with the law. However, no one can guarantee that we are being protected from restrictive orders, in exactly the same manner as they have banned Echo of Moscow. We finance our operation from the earnings received by the magazine, and journalists are working on a pro bono basis, one to two days a week.”

As sanctions against Russia have been introduced, YouTube has switched off monetisation in the country, which of course make’s Venediktov’s more difficult. But the social video platform continues to operate in the country – and Venediktov’s You Tube Channels are still not shut down – and he believes one reason for this may be its value to the Kremlin.

“The government also knows well how to use YouTube for propaganda purposes. By switching off YouTube they will switch off their own propaganda channels in the country. They first need to create a Russian analogue of YouTube which is RuTube, then maybe they will switch off the former. VPN systems are also still widely used in Russia. We can see that following the ban of Twitter, only 9% of subscribers were lost, and 30% by Instagram. In fact, we know that the government itself is planning to use this tool, and it’s not a good idea to ban the tools instrumental to your future operations.”

Beyond fake news: Understanding Putin’s propaganda

Of course, one of the key questions that many of us in the west keep coming back to, is how support for Putin can remain so high in the country, when those living within it do have access to outside information. How can such a large proportion of Russians still prefer the state version of events over what is clearly the reality?

“There are more complicated reasons for that, not just disinformation. First and foremost, Russia is a patriarchal country, quite paternalistic and people always preferred to agree with the power than to object to it. All the revolutions that took place in Russia in 20th and 21st centuries occurred among a minority of Russians – the majority was simply abiding them.”

“Following the annexation of Crimea, President Putin gave Russians a sense of pride. We can assert, it might have been a false sense of pride, nevertheless, it was a sense of pride. He is restoring post-imperial history, post humiliation. In reality, a huge number of people, mainly in provincial areas, believe he is a sort of a Batman, a saviour.

“Additionally, two years of epidemic created irritation and tension in people. They had to find an enemy. The government found an enemy for them. The words ‘Fascist’ and ‘Nazi’ for example certainly create an obvious reaction in people.”

“Propaganda isn’t everything but it is an important element. That is why when I chat with people close to the President, they believe that 70-80% of the population genuinely supports president Putin’s actions.”

“And a third important point is total propaganda, as in the totality of propaganda that overlays other issues. We can see this in the most recent news from Germany, where access to information is unrestricted. Listen, propaganda isn’t everything but it is an important element. That is why when I chat with people close to the President, they believe that 70-80% of the population genuinely supports president Putin’s actions.”

While the world is – finally, and thankfully – waking up to the effectiveness of fake news (and the ineffectiveness of BIG tech’s attempts to deal with it), the practical implementation and levels of sophistication involved in Russian propaganda still remain something of a mystery. But this is a programme that pre-dates even social media, and even in the case of Vladimir Putin specifically, has been more than two decades in the making.

“It wasn’t created on February 24th. This machine has been developed for at least 22yrs. When the young Putin came to power he showed us by his actions. He won presidential elections within six months starting from a base of 3% at the beginning. He clearly understood that his success was due to the media loyalty to him.”

“The first two actions carried out by Putin were to claw two federal channels back to the state from private ownership. The first channel was seized from Mr Berezovsky (Russian business oligarch, now deseased), and the NTV fourth channel was seized from Mr Gusinksy (Russian media tycoon). He was fully aware that the media is a weapon that paved the way to his presidency. Berezovsky supported him, Gusinsky’s channel didn’t but this didn’t matter – it all had to be under his control. He personally appoints the director general of each media outlet by his presidential order. Mr Earnst was appointed as a director of First Channel and Mr Dobrodeev – as a director of the Second Channel.”

“From the conversation I had with Putin in 2002, I understood that he treats all media as an instrument and not as an institution. It was his principal position – media is an instrument in the hands of its owner, it doesn’t matter whether the owner is a state or a private entity. I understood that he thought that if a media was in the wrong hands, inappropriate hands, hands of an opponent, he would seize the media from those hands, or remove the hands, or destroy the media.”

Nothing has changed since then, Venediktov tells us. In the mind of Valdimir Putin, the British media is managed by Johnson, the American media is managed by Biden, the French media is managed by Macron, and so on.

“He and his team sincerely believe in this concept. One third of Echo of Moscow was owned by Gazprom, but we didn’t follow a Gazprom agenda. That’s why to him, we were always a strange animal in the zoo. But as soon as an animal starts to bite and misbehave, they should break its neck. Therefore again, the sequence of events was quite predictable. It was all painful, uncomfortable, illegal, but it wasn’t unexpected.”

One piece of the global media jigsaw that has longsince remained out of place, is the portrayal of Russia by the west. It is a particularly difficult (and potentially dangerous) genie to let out of the bottle at the present time, when the lies being promulgated by the Putin regime are so obviously at odds with the reality of what is happening on the ground.

But there can be no doubt that over the years, western media has – either advertently or inadvertently – conflated the actions of the Russian public with those of the current – and previous – regimes. Negative stereotypes about the country’s people have never quite gone away, and this can of course create an ‘Us vs Them’ mentality.

So just how does Venediktov see this puzzle from within the country? Does ‘Russophobia’ still exist today? Is such division something that Putin is playing upon in his quest for greater public opinion? And how can western media do a better job, in 2022, of more accurately distinguishing between the state and its people?

“We can already see the situation where Russophobia (I don’t like this term much) is obviously present in a humanitarian context, and we see growing contempt for Russians. People see the suffering refugees, the horrible war pictures, and I understand that comtempt. And of course, those who committed crimes should be found and punished in this collective liability.”

Western media is also encouraging [anti-west] public opinion. When the western collective media assert that the entire Russian population will be held accountable, how will the Russian people perceive that?

“But people need to understand that Russians are second to Ukrainian people in suffering in this situation, regardless of their affiliation to the President. The consequences of these events will make an impact on each Russian, whether they are in the country or abroad, whether they support Putin or not. A similar analogy can be used talking about the German nation as a whole when it suffered from Nazism, including all the destruction, historical guilt, loss of close family etc.”

“And Western media is also encouraging [anti-west] public opinion. When the western collective media assert that the entire Russian population will be held accountable, how will the Russian people perceive that? How will inhabitants of Blagoveshchensk, Vladivostok, Belgorod, Moscow or St. Petersburg perceive that, if you make them guilty?”

“By playing this game you unite the everyday Russians and the elite into one snowball. Putin is trying to achieve that by all means, and at times western colleagues are simply playing his tune, his game. You don’t need to explain to a person of Jewish origin for example what anti-Semitism is, and make them feel guilty because they are Jewish. And so we need to be careful that we do not make everyday Russians feel guilty simply because they are Russians.”

“Putin simply wishes that to happen. We need to remember that, from the point of view of Putin and his team, the west is an ancestral enemy. It has always been an enemy, always wanted to humiliate the Russian Empire, the Soviet Union, the Russian Federation. And this lack of trust is not exclusive to the current team. Additionally again, the actions of the so-called collective west could be considered to be a factor as well. Thus, the grievance and mistrust accumulated throughout history shouldn’t be dismissed.”

Western media has also played a secondary part in helping Putin to promulgate his propaganda in a less obvious way: by restricting the flow of accurate international journalism into the country.

Venediktov explains: “The people are not able to see what’s really happening for other reasons – western media isolates the Russian audience from information by imposed sanctions. For example, I subscribed to multiple western media using my own bank card, but I cannot watch them now, since my bank card does not work! (due to sanctions against Russian banks). I am talking even about entertainment like Netflix or Amazon Prime.”

“I would like to thank those media outlets, such as those represented by FIPP’s members, who lifted the paywall access for Russian people and Russian journalists to their newsfeeds. This is a real help and a real important alternative source of information. We can’t pay, not because we don’t have the money, but because the cards and banking transactions have been blocked. And when such a media giant as the Financial Times opens their content for Russian readers willing to learn alternative information – this is a singular gesture of help.”

“I would like to ask other colleagues who have the opportunity to remove their paywalls for Russians. I don’t think it’s a huge monetisation for them. I address all of them – English, French, American, Spanish, Italian, German, Polish colleagues, all of them, the Baltic states as well. I have repeatedly asked them to do it when I meet with their representatives in Moscow, or when meeting their state’s ambassadors. It is vitally important for us.”

State of Play: Where are we today?

With consideration of international outlets in mind and looking at things more broadly, how does Venediktov view the current state of media today, both in Russia and beyond?

“We are an ‘old-style media’ and don’t follow the current trend of passing public verdicts. We accepted a long time ago that we don’t have all answers, and could only pose questions. Our questions may not be comfortable, but they are not answers. We can present and discuss the news with our audience and then each of our subscribers can make their own decision.”

“Nowadays, media passes verdicts, not necessarily with regards to war and Russia. But we can see it in the cancel culture, targeting journalists or presenters of good quality blogs or Twitter accounts. President Trump was a good example, was he a blogger? The number of his social media subscribers considerably exceeded the followers of traditional media accounts, like Washington Post, New York Times or Fox. Trump had much higher number of followers of his Twitter account. It’s popular and acceptable for outlets to call people bastards, monsters, etc. without any restrictions, but it’s not journalism.”

“I think the current level of noise is much higher, both in propaganda and anti-propaganda media. They throw verbal abuse at each other, everyone – from the President to his hottest opponents. It distorts the picture, It may seem trendy to shout abuse against your opponent, but in reality we will have to continue to co-exist together.The Echo of Moscow audience didn’t disappear anywhere. The propaganda audience didn’t disappear. Very often these listeners could be members of the same family.”

“However, we care about what we do, otherwise we wouldn’t be working in the industry, which is quite unsafe in Russia. Any war is bad for the media. Mass media start taking sides and transform themselves into civil activists. It’s all understandable. It’s normal to take sides and to protect the weak and vulnerable. It’s a normal feeling for a normal person to have an urge to protect the victim. Our job as a traditional media is to provide sensible arguments.”

Finally, in light of everything that has happened, specifically to Echo of Moscow, how does Venediktov see the immediate – and more longterm – future panning out?

“When Echo of Moscow was shut down and sanctions were imposed on Russian state leaders, one of the very influential leaders of the government called me and said: ‘Well, we were made younger by 40 years. Do you feel 30 years old, Alexei? Do you feel that everything needs to be started from square one?’ That made me feel that I need to start again, remember the past, Gorbachev’s times, perestroika.”

“I remember when Gorbachev was sharing his memories with me, how difficult everything was at the start. I used to tell him that I was in the thick of it myself, everything was exactly the same as I’ve been put in a position to do now. Yes, we have to start from the basics. Health and age are not the same but I am surrounded by 25-year old people. Everything is ahead of them – my job is to show them how I managed 30-40 years ago. If we need to, we will start from square one, but our principles of media broadcasting will stay the same.”

Ultimately, the Editor-in-Chief reminds us of the responsibility of media to report on the day-to-day, even when that may be playing out in extraordinary times:

“I always refer to my aphorism: January 21st will always follow after January 20th. Our life will not end on January 21st. Life didn’t stop on February 24th. We are people who need to explain to our audience what will happen thereafter. We are still living the moment of horror, but there is future and we need to be ready for it. This is how I see the role of my colleagues and my role as well.”