Time to bring sexy back to the publisher + advertiser marriage

After reading the article, it reminded me that licensing isn’t the only regime that’s ripping publishers off — the audited circulation model is also broken.

Advertising in the good ol’ days

In the glory days of print, ad rates were based on a simple “paid copies” model. Advertisers paid a fee that was based on a certain number of people, agreeing to pay a certain price for the possibility of accessing the print edition of a magazine or newspaper.

Whether readers picked up a publication off the porch of their house, at a newsstand or corner store, it didn’t matter. Whether they stopped reading at page two or 78 didn’t matter. All that mattered was the price they paid for the publication.

In hindsight we can debate whether it was a good model or not, but that too doesn’t matter. It was a model that reached consensus by both publishers and advertisers, with unbiased auditing agencies certifying the rates on behalf of both parties. Everyone got what they wanted.

All was well until the digital tsunami hit the printing presses. Almost overnight the paid circulation model that was arguably flawed from the beginning started to show its teeth, taking more than a bite out of publisher revenues. The dawn of the digital era gave light to the fact that the model was fundamentally flawed and simply would not work for online content.

Archaic advertising models hurt everyone

The price someone pays for the digital edition of a magazine or newspaper today is irrelevant and yet it’s still being used to measure the value of content in this antiquated carryover from print.

Is “willingness to pay” a valid measure to qualify a reader? Some may argue it is, but I believe it is a very short-sighted view on the true value of content consumer.

Perhaps one’s unwillingness to pay is a predisposed refusal to pay for online news. Perhaps willingness to pay is diminished by the inconvenience and frustration of hitting a paywall, or the fact that some publishers charge for the same content multiple times on different devices.

In today’s hyper-connected digital world engagement with content is much more indicative of a reader’s true value. And yet there is no ability within the current practices to measure the engagement of readers with either the editorial or advertorial content. The model also does not consider the changing demographics of readers and how they discover and consume content.

The paid audited circulation model isn’t just flawed; it’s detrimental to all stakeholders in the industry — publishers, advertisers and readers.

- Less revenue for publishers

The audience that is accessing news content today is often fragmented by interest, device, demographics and willingness to pay for online news. The existing ad model doesn’t recognise these non-traditional audiences so publishers can’t capitalise on the massive number of digital news readers that consume their content in multiple forms, multiple times a day.

- Less audience for advertisers

Audience metrics under the existing framework don’t add up because they don’t adequately qualify the readers that advertisers are actually reaching.

The model rejects a vast consumer base that accesses digital publications in airport lounges, in flight and in hotels. These issues are not included in the “headline figure” of the audit report because in the eyes of the myopic model, they are treated as “bulks” – another print relic that needs to be eradicated. In today’s digital economy these copies bring significant revenue to publishers, just not at the price point today’s system demands in order to qualify them as paid circ.

Discounting these “below the line” readers handicaps the judgement of advertisers who are making misguided advertising decisions fuelled by too much misinformation.

- Less value for readers

A model that dismisses the millions of non-replica readers that visit publishers’ digital properties on a daily basis brings no value to those readers. Non-digital models can’t possibly help publishers or advertisers deliver the right content (editorial and advertorial) at the right time, at the right price to this undervalued audience because it pays no attention to those readers and their needs.

Given how diverse and mobile digital readership is today, new, more adaptable ad models are needed to serve the interest of all readers, not just those that pay for digital replicas of printed editions.

Make the most of metrics

The metrics one can gather and analyse today about digital audiences that engage with editorial and advertising content are significantly more comprehensive than what exists in the print world. One would expect that this data would be highly valued and shared between publishers and advertisers. But sadly, that is not the case.

Many publishers are afraid to open the kimono to the wealth of behavioural analytics they have that show how, where and when readers consume content in digital publications. They worry that sharing how few readers actually venture deep into an issue would force them to reduce the advertising rates for internal pages that didn’t garner the same attention as the first few.

The standard print mantra, “If you’ve paid for an issue that means you’ve read it” seems to be a safer bet, but it is paralysing publishers’ abilities to capitalise on audience consumption trends and engagement.

Yes, there has been a slight relaxation of the minimum price point for digital editions in North America, but in other regions, that price can range from 25-50 per cent of the cost of a print edition.

And yes there has been some movement towards defining new metrics in some jurisdictions which try to measure audience and engagement with a brand’s content, but it is racked with inconsistencies:

- The way in which audiences engage with content across various digital properties and device types is very different.

- Measuring engagement on content that is consumed offline, as is the case with tablet apps, is technically challenging

- Online engagement is measured using services like ComScore and Google Analytics, while app engagement is measured purely on downloads.

There’s no easy solution, but that doesn’t mean that the industry should accept a model that clearly doesn’t work for anyone. It’s time to innovate collectively to define new metrics that serve publishers, advertisers and readers. And with today’s highly fragmented and mobile audience, the need for some form of standardisation across the world has never been greater. That doesn’t mean one rule should fit all, but with content being consumed around the world, alignment between the national auditing agencies and this global industry is long overdue.

Here’s just one example…

There has been a long standing policy in Australia that any content that’s consumed outside of the country does not get counted by the Audit Media Association of Australia (AMAA). So if someone from Sydney decides to fly to Los Angeles using Qantas, the Australian newspapers they read while on board (and paid for by Qantas) are not counted. The moment the wheels leave the runway that loyal reader of local papers suddenly stops being a “qualified audience”. In the month of April alone, Qantas International flew with close to 500K passengers! And every one of those passengers is considered irrelevant in AMAA’s wonky world of audited circ. Pure insanity!

It’s time to talk

Needless to say, the industry is tortuously slow to adapt. But there’s slow and then there’s “no go”. No one is really talking about the problem; they’re not committed to changing it or even debating about what needs to be changed. It’s like they’re afraid to rock the boat, even when the ship is clearly sinking.

What was once a level playing field with publishers and advertisers, with each compromising to reach consensus, has turned into lopsided war of wallets. Because publishers are just one of the millions of digital properties where ads can be placed, clearly advertisers have the golden rule (He that owns the gold, rules.) advantage in this relationship.

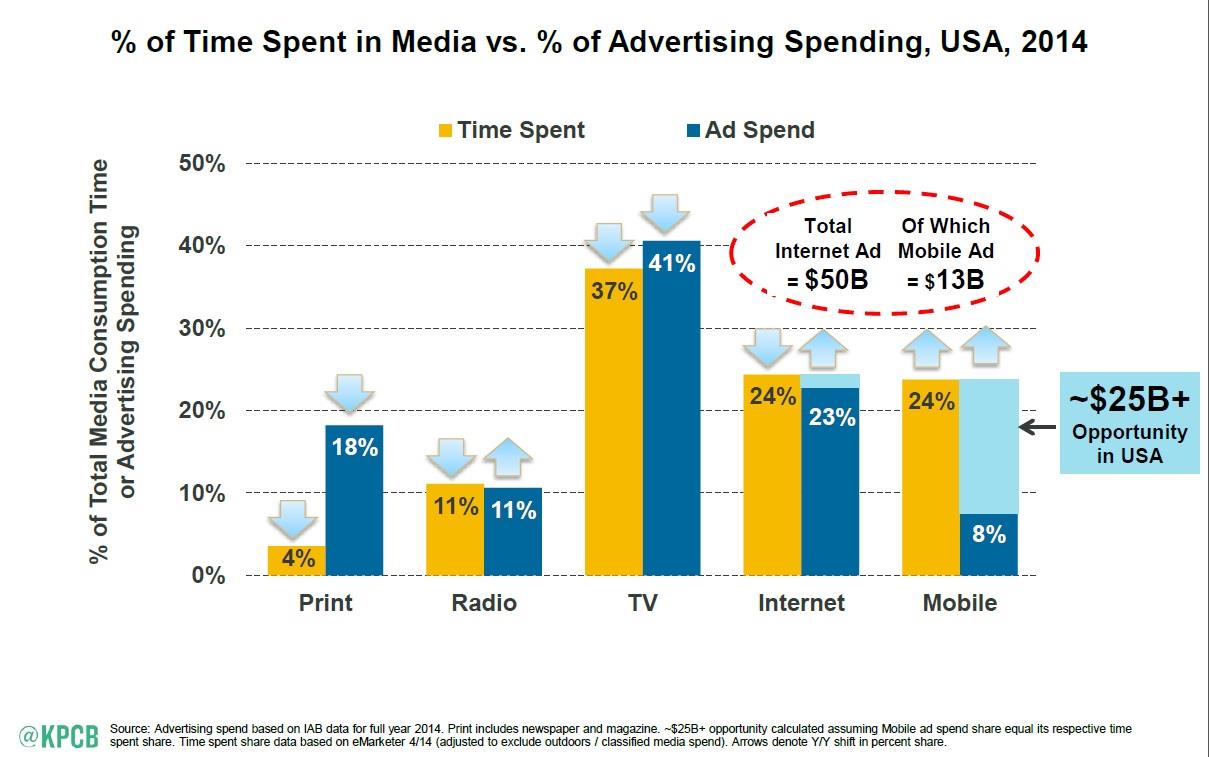

And as the relationship between publishers and advertisers continues to tilt the scales in the wrong direction, advertising on the internet has become commoditised. Thankfully, monetisation opportunities on mobile are huge!

But so are the technical challenges of serving up ads in an engaging and effective way. One can’t shrink desktop banner ad into a smaller footprint and expect it to work, which sadly is exactly what publishers tried to do (and failed).

In the industry’s attempt to grab the attention of users, it’s done everything possible to disrupt, irritate and disengage audiences on mobile devices. Publishers high-jacked screens and forced users to perform some function in order to close a banner ad that was blocking the content they wanted to see. When that didn’t work, things got really ugly with annoying animations, flashy promotions and ads with inappropriate imagery. A great opportunity to engage with readers backfired by a total lack of appreciation for the needs of publishers’ most precious asset – their audience.

It’s not that publishers don’t know how to present compelling and engaging ads; they’ve been doing it for decades in print magazines with glossy ads. Glossy ads aren’t intrusive; they are seamlessly integrated with the content and drive engagement with, and between, readers. Newspapers could learn a lot from what magazines have done in this area. The challenge is how to transfer that same emotional engagement from print to the web and mobile web.

No time to waste

Instead of chasing digital dimes publishers should be working to solve the premium placement problem with digital advertisers, especially with luxury brands that are struggling to find digital properties for their display ads where quality trumps quantity and brand equity is enhanced through the medium.

Publishers should also be qualifying and segmenting their audience in ways that would be more attractive to advertisers looking to reach a targeted, and sometimes niche, audience. Small targeted audiences shouldn’t equate to lower ad prices; on the contrary, publishers should be able to demand higher ad rates because they can deliver highly-qualified consumers to discerning advertisers. Price-per-lead should be controlled by the publishers, not the advertisers. Remember who owns the ultimate buyers – the “gold” in this scenario belongs to the publisher.

In this publisher-powered new world, the role of the audit bureaus would be diminished; one might even go so far to say these agencies would become irrelevant.

In a recent panel on advertising in New York, one agency representative talked about their level of engagement with the publishing community and that in years past they used to spend US$1.5bn annually on ad placements. Today, that spend has shrunk to ~ $100M. Unless we want to bring it down to zero, which can happen very quickly, we need to act now!

New forms of advertising (e.g. programmatic and native) bring new opportunities and should definitely be in the media mix. But in the end, resurrecting the industry can only come with fundamental changes in how publishers’ massive audiences are nurtured, measured, qualified and served.

Google and Facebook have done it with content they don’t even own. So why can’t magazine and newspaper publishers who engage with a massive audience of readers on at least a daily basis on multiple platforms do the same thing? They can!

First they need to get up close and personal with their readers and understand how, and where, they want to discover and consume content. Then give it to them the way they want it.

This will mean investing in digital in all its forms, including digital editions and mobile apps. Producing a flat, non-interactive PDF of a printed edition is not a worthwhile investment; it will fall flat in terms of engaging with readers and measuring that engagement to improve both editorial and advertising content.

Publishers’ digital properties must be much more sophisticated than what they have today (think multi-media, socially-engaging features, interactivity and click-to-transact ad technologies) in order to grow audience, engage with readers and then collect, analyse and segment the data to qualify them and prove their worth for advertisers.

And last, but not least, publishers need to engage more with the advertisers that “fit” with their audience and their brand. They must work collaboratively to maximise the ROI for both parties, always remembering that the audience is the gold in the transaction, not the real estate.

The price for advertising should not sit with ancient audit bureaus that know nothing about a publisher’s own audience or the value of their content and digital real estate. It should belong to the seller and negotiated with the buyer like it is with most other industries.

The only choice is change

By holding on to the print paradigms of the past and letting fear, uncertainty and doubt infiltrate the industry, publishers have been impeding progress to a brighter future for themselves, their readers and their advertisers.

Change won’t be as easy as “ABC”, but as the famous Chinese philosopher, Lao Tzu, so aptly put, “If you do not change direction, you may end up where you are heading.”

More like this

When it comes to Smartwatches, it’s all about the wrist, NOT the words