Can slow journalism march on… slowly?

When former MSNBC anchor and NBC News correspondent Ronan Farrow’s 8,000-word New Yorker story (From aggressive overtures to sexual assault: Harvey Weinstein’s accusers tell their stories), detailing allegations of sexual harassment and sexual assault by Harvey Weinstein appeared on 10 October of last year, one of the first sentences in the story makes it clear that the report was the result of an investigation over the course of ten months. During the ten months, the report reads, Farrow interviewed thirteen women who said that, between the 1990s and 2015, Weinstein sexually harassed or assaulted them.

Recalling the almost year-long investigation, Farrow told CBS’s Gayle King during an interview in front of a live audience at this year’s American Magazine Media Conference in New York of the respect he developed during the time for New Yorker editor David Remnick who not only encouraged and supported him during his research but also granted him the freedom to conduct such a long and comprehensive investigation. He explained, among other things, why – along with Remnick – they decided that to publish this story first was not the most important consideration, but rather to publish it right.

Standing up to scrutiny

In fact, five days before his New Yorker exposé was published, the New York Times, in a report by journalists Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey, revealed multiple allegations of sexual harassment against Weinstein. It was the Times article which led to the resignation of four members of the Weinstein Company’s all-male board and to Weinstein being sacked.

Asked by King if he was ever asked to “hurry up” to get the feature published, Farrow emphasised that because of “the set of journalistic values” at the New Yorker, they were adamant that the story should only run when it was “100 per cent ready and properly fact checked”. Even when they learnt that the New York Times journalists were ready to publish their own account of the Weinstein saga, they stuck to their decision not to rush the story. Underpinning this decision was the conviction that they should “not cut short Weinstein’s window to comment” and not in any way jeopardise their fact checking process. Their version of the facts “needed to be able to stand up to severe scrutiny”, explained Farrow.

Tying into the current debate about fake news, Farrow hailed the editorial approach and conviction of the New Yorker, for which his reporting won the magazine the 2018 Pulitzer Prize for Public Service, sharing the award with The New York Times.

“The playbook the New Yorker used in breaking this story is the model (to combat fake news),” said Farrow. “You don’t skimp on fact checking. You don’t skimp on the legal review. You have a process run by brave journalists… and you insulate the reporting from any kind of corporate interference.”

Get stories like these every week in your inbox. Subscribe to our (free) FIPP World newsletter.

Filling the news abyss

This approach is echoed by Rob Orchard, editor of slow journalism magazine Delayed Gratification who has warned that, “being first in today’s news environment has (unfortunately) become much more important than being right”. Says Orchard: “This has forced journalism to take a turn for the worst as fundamentals like accuracy, impartiality, context and depth of reporting are being abandoned in the scramble to get reams of text online”.

|

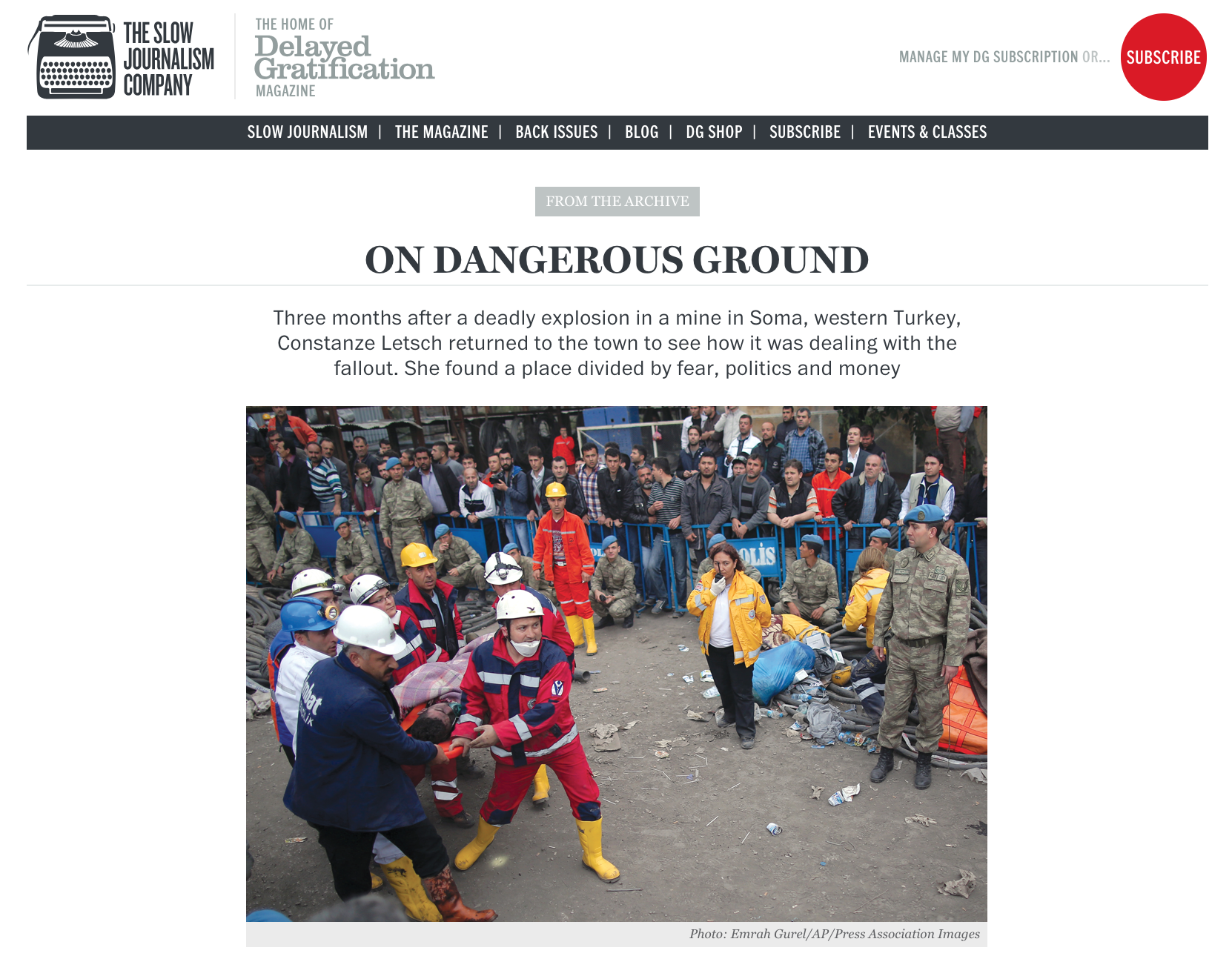

But Orchard warns that slow news should even go beyond the fundamentals of accuracy, impartiality and context. Too many news agencies, he says, pick up news stories and leave them once the hype has blown over. It is the task of slow journalists to “fill the abyss” left in the wake of the 24/7 news cycle. An example of this is how Delayed Gratification continues to cover the aftermath of the 2014 coal mine disaster in Turkey long after most media have departed.

British newspaper The Times also realised that the 24/7 news chase might not yield the best journalism – or online engagement. Just over two years ago they abandoned the online breaking news cycle and reverted to three digital deadline-driven editions a day. At the time, industry insiders frowned on the move but now the paper is claiming wholesale success. The ‘editions approach’ to digital publishing is working, says the paper. Within the first year of slowing down their digital news delivery pace, pageviews on their mobile app were up 300 per cent, subscribers to the mobile app and website rose by 20 per cent, users of the app grew by 30 per cent, articles read per website visit jumped by 110 per cent, and even the paper’s print edition circulation saw increased sales of 9.5 per cent.

Much in the same way statistics and blow-by-blow reporting can fail to relay the full impact of an ongoing news story. One of these is the opioid crisis (the misuse of substances that produce morphine-like effects) in the US, which has been the worst addiction epidemic in the country’s history. Drug overdoses now kill nearly 64,000 people a year.

Realising that statistics alone cannot tell this story, Time magazine – for its March issue this year – commissioned veteran conflict photographer James Nachtwey to document the crisis. Nachtwey, who has documented a variety of armed conflicts and social issues around the world, travelled for over a year with Time’s deputy director of photography Paul Moakley to shoot the Opioid Diaries, the first issue in Time’s 95-year history devoted entirely to one photographer’s work. The volume of work captures the reality of people, their families and first responders living or are being impacted by the addiction epidemic every day. For the online version of the exposé, the images are paired with voices from Moakley’s interviews.

|

A slow cover shot

Time revisited the themed edition approach when it devoted its June special edition to ‘The Drone Age’. This time around Time took slow journalism one step further to also encapsulate it into the methodology of shooting its cover image. In the magazine’s 95-year history its cover was never photographed by a camera mounted on a drone. Working and planning meticulously for months with Intel’s Drone Light Show team Astraeus Aerial Cinema Systems, they used 958 drones with LED lights to create a 400-metre high actual version of the magazines’ iconic red border and logo in the sky to shoot the cover image.

|

Wired, the US magazine specialising in how technology affect culture, the economy, and politics, also took a break from the blow-by-blow reporting about the controversy Facebook has found itself in during the past couple of years by taking several months to interview 51 current and former Facebook employees about issues ranging from the battle against fake news to questions about user privacy.

The result was a special cover report in Wired’s February edition this year entitled ‘Facebook’s two years of hell: inside Mark Zuckerberg’s struggle to fix it all’. The special report is a promising example of how slow journalism can be executed by a title that is better known for its daily online updates of news about platforms.

|

As honourable as the intentions of some magazines that wade into slow news now and again might be, there are magazines – like Delayed Gratification – that are exclusively dedicated to slow journalism. Ernest, a British biannual printed journal and blog “for curious and adventurous gentlefolk”, is a super example, says Samir Husni of the Magazine Innovation Center at the University of Mississippi. The magazine is about “curiosity and slow adventure”, says Husni, and “nothing describes what a print magazine can and should deliver than those words”.

As a bi-annual journal for “enquiring minds”, it values surprising and meandering journeys, “fueled by curiosity rather than adrenaline and guided by chance encounters” and acts as a guide “for people interested in craftsmanship, curious histories, eccentric traditions and those who care more for timeless style than trends”.

Slow journalism as a movement is finding traction both within academic and industry spheres. The world’s first ever slow journalism conference was held during the last week of June this year at the University of Oregon, organised by Peter Laufer, the James Wallace Chair in Journalism at the university’s Oregon School of Journalism. Laufer is the author of the 2014 book Slow News: A Manifesto for the Critical News Consumer, which examines the nature of news in the context of the increasingly frenetic pace of modern life in the twenty-first century. The conference was attended by academics and publishers from around the globe.

Slow journalism, through a presentation by Delayed Gratification, also has an important presence at the current exhibition at Somerset House in London entitled ‘Print! Tearing It Up’, which charts the evolution of print publications and celebrates the diverse industry of innovative independent magazines. The exhibition ends on 22 August.

Someone’s got to pay

Slow journalism magazines like Ernest and Delayed Gratification survive because enthusiasts are prepared to pay hefty subscription fees. Ernest starts at GBP£21.50 (US$28.70) an issue and Delayed Gratification at £36 ($48) for an annual subscription of four issues.

Meanwhile the surviving world magazine industry in an age of disruption is zooming in on ways to increase return on investment on every piece of content it creates. In other words, if time is money, how can an organisation sustainably decrease the speed at which it creates content? As the Nieman Institute reports, philanthropic grants and/or crowdfunding has been behind some great examples of slow journalism, like Pulitzer prize winner Paul Salopek’s ‘Out of Eden Walk’, a seven-year quest to walk across the world and report every step of the way with some long pieces for National Geographic and shorter pieces as part of a personal blog.

But philanthropy is not a business model. Ultimately, reader revenue needs to pay for slow journalism, which simply means audiences will have to be prepared to pay – more – for accuracy, context, impartiality, facts that can stand up to scrutiny and “fill the abyss” left in the wake of the 24/7 news cycle. How long slow journalism can survive will depend on publishers’ ability to leverage exactly this.

More like this

The New Yorker’s investment in quality content, explained

How The New Yorker brought the soul of the magazine to the web

Media Voices podcast: PressPad founder Olivia Crellin on the need for diversity in journalism

[Video] Juan Señor: Reader revenue, not new technology, will be the salvation of journalism

BBC Travel – how multimedia galleries are (not) changing good storytelling

Far & Away magazine: the result of NatGeo’s storytelling and WSJ’s global insights