How digital tools can transform newsrooms: cultural shifts and the growth of collaborative fact checking

One man who is hugely passionate about digital tools and their potential to transform newsrooms is Mark Stencel, co-director at the Reporters’ Lab, Duke University. In addition to highlighting issues around digital adoption Mark and his team have also worked on a fact checking system that has attracted wide support from across the media.

|

At DIS Mark will be explaining how the collaboration came about and what newsrooms can learn from the process about innovation and working together.

***Registration for DIS 2018 (19-20 March in Berlin) is now available. Sign up by 13 March to avoid late booking fees. Secure your place here***

|

You say you think there is a reticence in some news rooms to try out new digital tools – why do you think this is the case?

We saw that a few years ago when we did a study for the Duke Reporters’ Lab. We noticed that there was a lot of foundation support for building new digital tools that would help news organisations do storytelling in new ways. You’d hear a lot of talk about these tools at journalism conferences. But we also noticed that the vast majority of news organisations were not actually using any of them. That was especially the case in local news organisations in small and medium-sized US media markets. There was a big divide between the digital haves and have-nots.

So we asked editors and top producers at those news outlets why their companies weren’t retooling, since the tools we were talking about were mostly inexpensive if not free. And we heard versions of the same answers over and over: know-how, time, and money.

“We don’t have the digital know-how to use tools like that.” “We can’t afford to hire the people who already know how to use those tools.” And, “Hey, we’re busy! We don’t have the time to learn how to use those tools. We’ve got news to cover.”

We called this “the goat must be fed” problem – because that’s what one local radio news director told us when he explained why his staff wasn’t using any of this stuff. This was a very well-staffed news organisation in a big city, but he still called it “the kind of work I wish we could do.”

On the other hand, there were some local news organisations in comparable media markets that were using new tools to so better journalism. And they had all of the same problems as those organisations that were not using the tools had. They didn’t have time, money or know-how either. So what was the difference? That’s the question we tried to answer in our 2014 report, and we are using those lessons now, in our work with journalists in the fact-checking movement across the US and around the world.

What type of tools are you talking about? Can you give me an example of how a newsroom has adopted a tool and it has been transformative?

In some cases very basic data and digital tools: spreadsheets, maps… DocumentCloud is a relatively well-used tool for managing, sharing and annotating large caches of documents – the kind of information a government agency in the US might hand over to journalists in response to a Freedom of Information Act request. What a great way to be transparent and show your work. Don’t take our word for it, public. You can read the documents we based our story on for yourself. Many news organisations and individual reporters have used DocumentCloud. But even that long list of users is still much shorter than the list of state and local newspapers and broadcasters that could and should be using it.

How can this situation evolve? Is it a top down cultural change that has to be instituted, or should passionate and tech savvy individuals be driving change?

Ideas are often bottom up. A reporter or producer identifies some software that helps them cover a story in a new or different way. Spreading that lesson across the organisation requires leadership. The difference we found between the news organisations that were digitally retooling and those that weren’t was they had leaders who understood that technology could make their newsroom’s journalism better and reach more people. And they set priorities – in hiring and coverage – that made those changes happen, even if it meant not doing something else their organisation had always done.

Ultimately, time, know-how and money are all things news leaders control. So, for example, instead of endless daily stories about daily traffic accidents – most of which are likely being covered in the exact same way by other local news competitors – you could turn that same information into data and do more important accountability reporting about types of traffic accidents, or problem points in the road system and so on. And then a small story becomes a big story.

We can apply those same principles to re-tooling the way journalists fact-check statements by politicians, government officials and other influential people.

Explain your work with fact checkers. How did the university attract the investment, and where do you think that you will take fact checking in the future? Is the dream of instant political fact checking available digitally now a reality?

So the fact-checkers we’re working with are not proofreaders. They’re the journalists who look at what influential people say publically and report about who’s telling the truth and who’s not. It’s a mix of accountability and explanatory reporting.

The Reporters’ Lab, which is led by PolitiFact founder Bill Adair, played a key role in convening what has become an annual international fact-checking summit. And two years ago that led to the formation of the International Fact-Checking Network based at the Poynter Institute, a media training institute based in Florida. So we start with those long, strong bonds to more than 140 fact-checking projects all over the world.

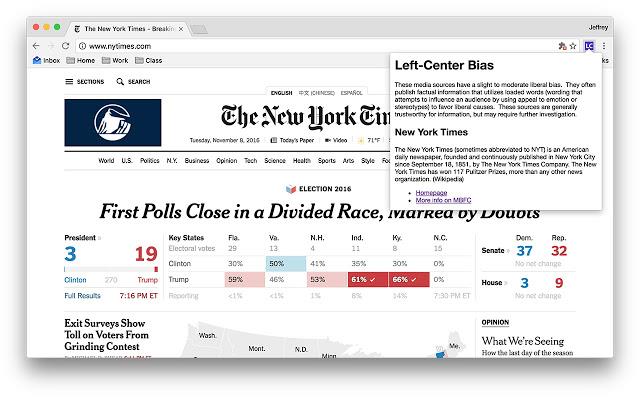

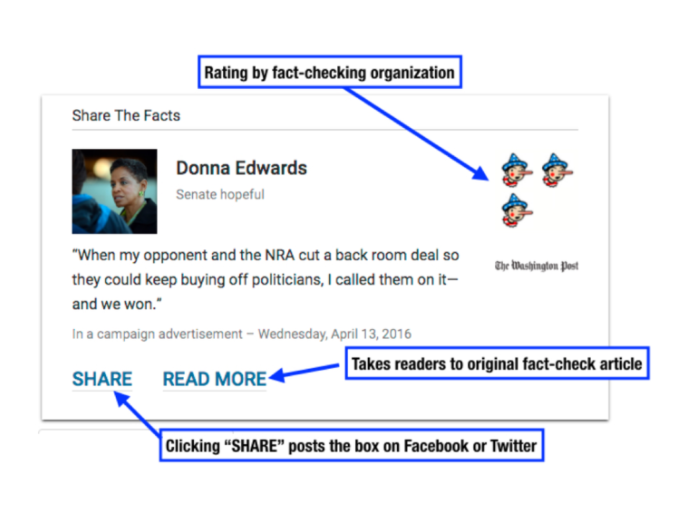

A year ago we worked with Google and Schema.org to establish a common tagging system for fact checks. The idea started with one fact-checker – Glenn Kessler at The Washington Post – and it has turned into a database on thousands of statements that we call Share the Facts. Google and any other platform can now use these tags to easily identify and surface fact-checks – like the fact-checking box that now appears on the Google News homepage. We’ve even prototyped applications for the Amazon Echo and Google Home to let people at home query the database and get answers.

That work showed we could get journalists from different operations, using very different publishing systems, to work together. And last year, we received additional support to take that work further – US$1.2 million from Knight Foundation, Facebook and Craig Newmark, the founder of Craigslist. This created the Duke Tech & Check Cooperative, an interdisciplinary collaboration that starts with the fact-checkers, but also includes technology partners at the University of Texas at Arlington, The Internet Archive, the Bad Idea Factory and Digital Democracy at Cal Poly-San Luis Obispo. Plus we have our own staff and student researchers. And we are collaborating continuously with other organisations that are working on the same technical issues, from Full Fact in the UK to Chequeado in Argentina.

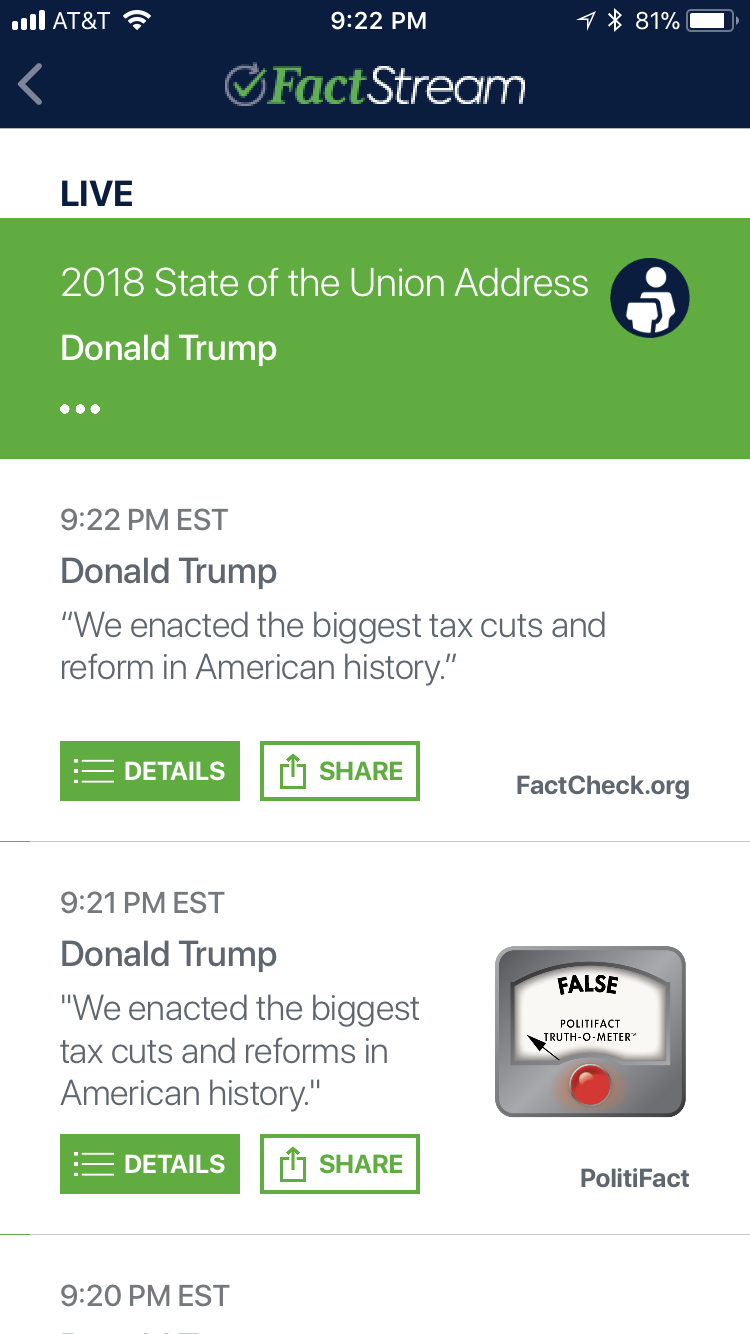

All of us are working on different problems and products. How to automatically detect and recognise a factual statement. How to see if that statement is similar to one that’s already been fact-checked. Who said it? How do we notify fact-checkers? How can we accelerate and elevate their reporting? And ultimately, how can we connect enough of those processes to automatically and accurately tell citizens when someone in a position of power has said something misleading in something close to real time. We are trying to address each challenge one step at a time.

How do you think newsrooms should use fact checking tools – and how might it help them overcome their reticence to use digital technology in this way?

In our first few months, the Tech & Check development team deployed a new live fact-checking app that, among other things, uses the Share the Facts database to accelerate the reporting process. For the app’s debut in January, three competitors – The Washington Post, PolitiFact and factcheck.org – all joined forces to fact check President Trump’s annual State of the Union address in Congress. The collaboration is efficient and the app showed that we could elevate and spread their work.

|

That same month, behind the scenes, we began providing a series of daily alerts to a group of fact-checkers. The alert process scans and scrapes information – TV news transcripts, legislative proceedings, social media feeds – and then uses the ClaimBuster algorithm developed by computer scientists at UT-Arlington to flag and rank statements the fact-checkers might want to report on. Connecting that with Share the Facts will also allow us to flag statements that have already been fact-checked.

For now, that means we’ve built a helpful robot intern that reads more, faster than small teams of fact-checking journalists will ever have time to read. But it also means we’re perfecting the tools that can reliably detect newsworthy statements, and then ultimately intercept some of them with automated fact-checks.

How have you got newsrooms to work together? Do you think this a trend – how can you encourage best practice?

It helps that we know how the fact-checkers work. So we can design tools that accelerate their existing workflows. We also offer incentives. The small amount of extra work it takes to tag their fact-checks for Share the Facts creates a database that elevates their work and drives more traffic. And it will ultimately saves them time – because we accelerate their reporting process with alerts that are powered in part by searches of their past work, or because we’ve made their past work easier to deploy when they want to fact-check a news event in real time. Our motivations and goals are aligned.

What drove the live fact checking experiments on Amazon Echo and Google Home, and what do you hope to achieve with these?

Both of these applications were ways for us to demonstrate how the Share the Facts database could help us access and deliver this journalism in new ways. They also are giving us ways to learn more about Natural Language Processing. There are a lot of ways to tell a lie. How many can we detect?

More generally do you think that technology can repair the relationship between the media and the population and that news sources can be trusted again? Do you think social networks also have significant role to play in re-establishing trust?

Partisan attitudes about news organisations extend to fact-checking. And, as FactCheck.org’s founder Brooks Jackson has often said, politicians have been lying for thousands of years. So there’s only so much we can do about any of that. But fact-checkers may be able to help re-establish a common set of shared facts. If we can do that, and perhaps offer the rest of the news business some lessons in the power of collaboration and technological efficiency, we’ll have turned all the small steps we’re talking about right now into a real giant leap.

Fortunately for me, it’s hard to fact-check a prediction. But I think that one will stand up to the Pinocchios and flame-retardant pants of future fact-checks.

***Registration for DIS 2018 (19-20 March in Berlin) is now available. Sign up by 13 March to avoid late booking fees. Secure your place here***

|

More like this

How Egmont is reaping rewards from creating ALT.dk

How traditional media know-how helped Visual Statements become a social publishing success

Blockchain: can it transform the media? Yes, says Burda CTO

How this startup plans to use blockchain to power a new media business model

How Cheddar revolutionises business media

Zuckerberg and the ‘trustworthiness’ of publishers

Voice control and driverless cars – the future at CES 2018