The Mr. Magazine™ interview: New York magazine EIC Adam Moss on mag covers, long-form journalism and more

Being Print Proud Digital Smart isn’t just a mantra for showcasing a certain way of thinking when it comes to magazines and magazine media today. The phrase is much more than four words strung together in a random order that makes sense. It’s a vibrantly healthy way of doing business in today’s rapidly changing world of media publishing. New York Magazine and its very humble, and hard-working editor, Adam Moss, has a firm grip on this prescription for success. And why wouldn’t they? They have been looking at the web as a way to build business and not steal it from print years before anyone else had even heard of the word paywall, let alone knew what it meant.

And while the magazine’s editor-in-chief would never admit that he had a definitive hand in all of the success he and New York Magazine have seen, him earning Editor of the Year for guiding the magazine’s election coverage in 2016 and the magazine winning the overall Magazine of the Year Award when ASME gave out the Ellie’s, it’s obvious to the naked eye that the two of them were made for each other.

I spoke with Adam recently and we talked about many things, one of which was his celebrated abilities as an editor, yet his very un-celebrity type style when it comes to him presenting himself to the rest of the world. His response, and I paraphrase, he would rather his work speak for itself. And as the awards mount up and the magazine continues to buck the odds by making more revenue digitally than with its print component, Mr. Magazine™ would have to say his work definitely speaks for itself. As does the Print Proud Digital Smart nature of the brand.

So, I hope that you enjoy the Mr. Magazine™ interview with Adam Moss, a magazine editor that I have followed and observed since 1988 when he launched 7 Days magazine in New York City. It was a delight to talk with Adam, and I am delighted to bring you this most engaging conversation.

But first the sound-bites:

On why he is a “celebrated” editor but not a “celebrity” editor: I think the reason I’m not a celebrity editor is that a ‘celebrity” editor is a somewhat different thing than an editor. And I’ve just never been comfortable doing celebrity-like things. I do my job and I hope I do it well. The more performance aspects of being an editor were never something that I was especially well-suited for.

On his concept of editing and creating a magazine: Well, of course, it’s changed over the years. Early in my career, I was very lucky to have worked at Esquire when Phillip Moffitt was the editor. He was fairly new to editing, certainly brand new to editing when it came to a magazine the scale of Esquire. So, to help him he brought in all of these legendary magazine editors from the ‘60s and ‘70s. And I was a junior editor at the time, and as he was being taught by this group of veterans, so was I.

On how he balances being Print Proud Digital Smart: By hiring good people who know things that you don’t know. And then you learn from them and try to help them think about things in a certain way, but essentially you let them do their jobs. As everything gets more complicated, the role of an editor is to hire specialists and let them do their thing.

On whether he feels more like a manager today rather than an editor: I certainly enjoy editing much more than I enjoy managing. (Laughs) But yes, inevitably, as the organisations that we run, in order to put out magazines and other content, get bigger, you have more and more the job of management, which is a necessary evil.

On his belief that an editor’s job is to know that great magazines are steeped in point of view, voice, and tone: Your main job is to understand what the point of view ought to be and to constantly evangelise it within your own organisation, and try to coerce the organisation to adapt and speak in that point of view. That’s an essential job.

|

On deciding what content goes where when it comes to the print and digital platforms: Well, you ask yourself where the audience is for an individual story. And the answer is usually obvious. But often, very often, you publish it in more than one place. Certainly, anything that is in the print magazine is then published on “Vulture” on “The Cut” or “Daily Intelligencer.” And often, something published on Daily Intelligencer also runs on The Cut because it’s of interest to The Cut reader; it’s of interest to the more politically-obsessed Daily Intelligencer reader. You just have this huge canvas now. And you use it in the most creative way that you can think of to reach the maximum audience that story might get.

On whether he thinks we are reaching a danger spot today, in terms of long-form journalism and storytelling in journalism: I think there are lots of threats to what we do, but I don’t believe long-form itself is in danger. In fact, because you can reach so many people through digital distribution, you can find readers for almost anything. And there’s a big, big audience out there for our longer stuff. Our longer stuff tends to do way better than the shorter stuff. It’s a good business to be in to make longer-form journalism. People really like stories and they like storytelling.

On the print platform now being biweekly, but the brand itself being by the hour or by the minute: By the minute, exactly. (Laughs too) When we went biweekly, the point that we were trying to make was that we were trying to adjust to the way in which people now read. They want an instant response to what is happening in the world and we provide that. And then they also want a deeper, more meditative content, not necessarily on a weekly schedule, which made us comfortable with having our stuff read on a biweekly basis.

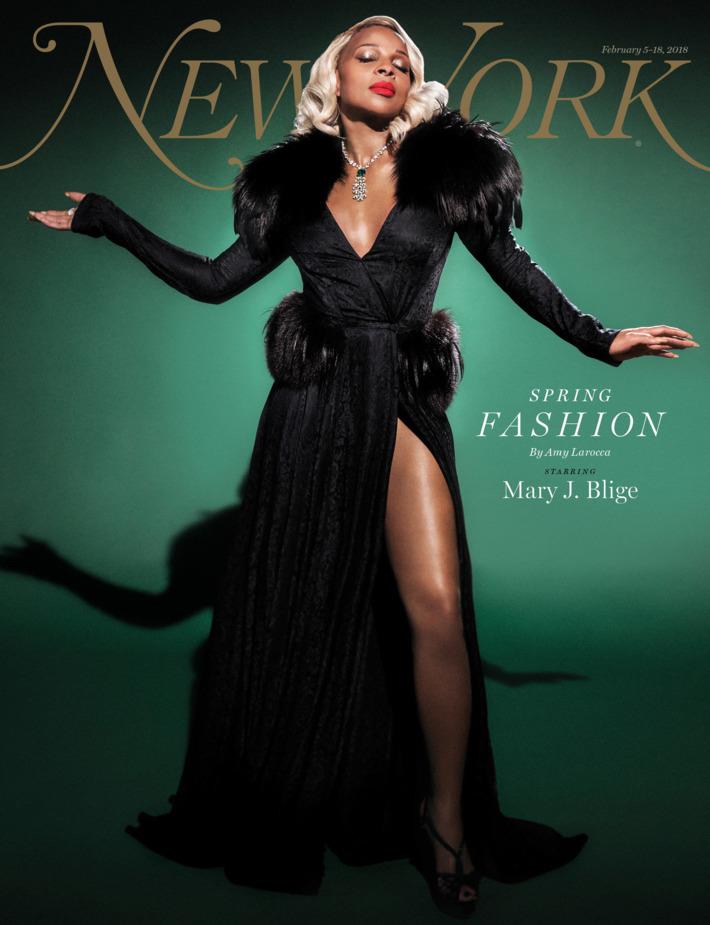

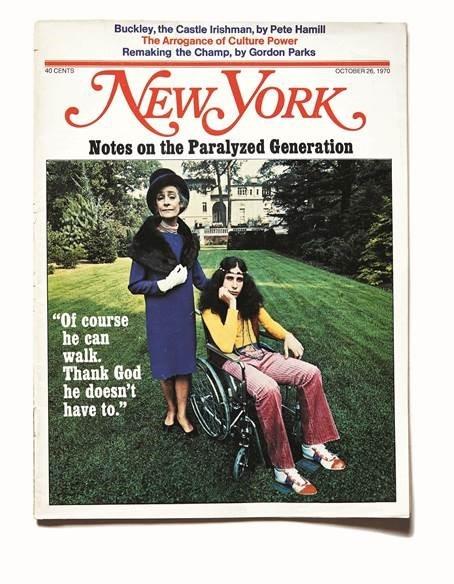

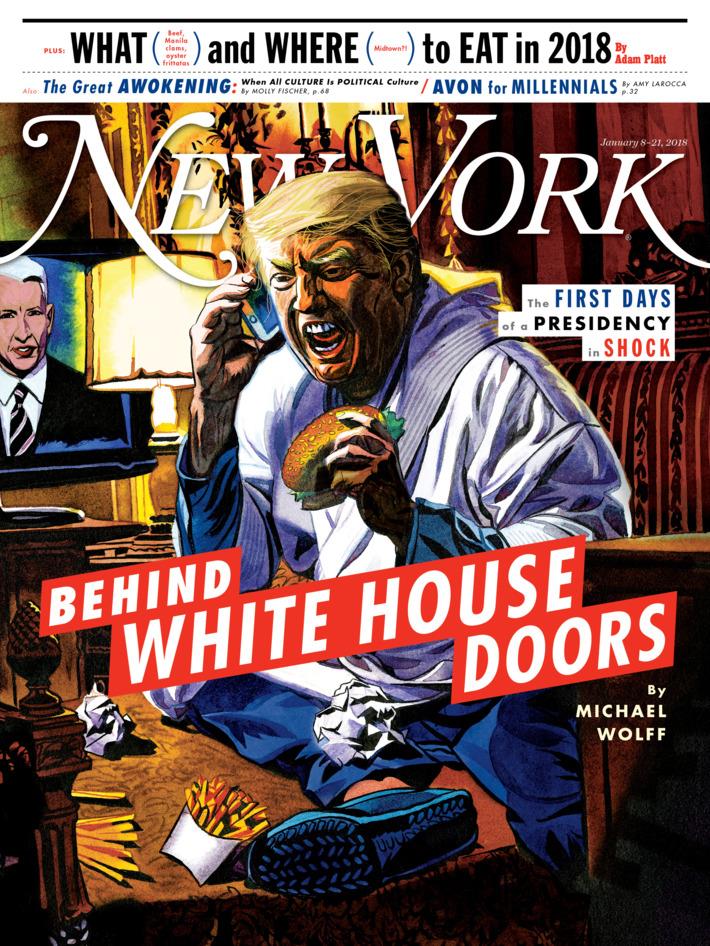

On whether he thinks there is somehow a halo around a printed magazine cover that does not exist in digital: Probably. The cover is no longer really to sell magazines on newsstand. As newsstands have become so much less important to all of us, the cover has a different function. It is basically the brand statement of what we make. It declares what we think is important or interesting; it declares our voice. Also, it’s an amazing document for the purposes of social media. Social media takes your cover and distributes it all over the place and it becomes an advertisement for the magazine that’s actually more important than it was originally meant to be when it was to stimulate newsstand sales.

On whether he thinks this new idea of magazine covers is good or bad: I try not to think in those terms, because everything is both. Things change; there’s no fighting the things that change. And you just have to adjust to them and think of them as opportunities and not as problems. And I think basically most of the changes have been, not all, but most, have been for the better.

On being one of the few magazines that makes more money from digital than print: We’ve been at it for a very long time. We’ve been at it way longer than most, if not all, magazines. The story of New York and its digital incarnations have preceded me being here. It was kind of coincidence that the previous owners of this magazine went into a joint partnership with Cablevision in order to do their website. There was a website called New York Metro, and New York Metro had the magazine on it and it also had listings and that sort of thing. It was ahead of its time in that way, but it had one other thing that was crucially important, which is the reason that Cablevision wanted the partnership because they wanted to promote a fashion show that they had called “Full Frontal Fashion,” I believe. And what that meant was the promotional device was to run the runway pictures on the website. This was before any fashion designer had his/her own website. So, we were the only place you could get runway pictures, which meant that we got a lot of traffic from the very beginning.

On why he thinks magazine media created a welfare information society at the beginning of the digital age and offered for free the only product they created: It was similar to what almost all content fields did. The music business was famously very confused by the beginning of the digital age. People needed and wanted to get information for free and from the music side, it was easy to steal music. Everybody has been confused about how to make money off of digital habits. And I think the magazine business has been confused too. And it’s only now beginning to reckon with that in a serious way. That’s why you’re seeing paywalls and ecommerce, which we do here, actually very successfully. But also, our experience was that you could actually make advertising money off of the digital content. And so, we did that too.

On whether he feels the brand is a projection of himself: It’s a projection of a group think, and it’s the editor’s job to get the right group together to have that group think. So, it’s not because of me exactly, but it is a projection of a worldview that I’ve helped shape here. And it’s the product of a lot of people thinking. I can’t say that I’ve done anything particularly on purpose. The reason that I’m not out there giving parties and that sort of thing is because I can’t. (Laughs) Not because I willfully decided that was a bad tactic. I actually think it’s a good tactic. I think it’s often very helpful for places to have magazine editors with a higher profile. But for me, that’s just not the way that I work. For me, what it’s about is the work, and that’s what interests me.

On whether he is the longest-serving editor of New York Magazine so far: Yes, that is now true. It happened about two years ago that I passed Ed Kosner, who previously held that honour. I’ve been here almost twice as long as Clay Felker himself was here. I’ve been here forever.

On what we can expect in the next seven years from him and the magazine: I can’t even tell you what to expect tomorrow. (Laughs) This business changes so fast. And it’s a race to catch up to the changes in the business and also, of course, the changes in the world and what we cover.

On what piece of advice he would give upcoming editors or future industry leaders: Listen and watch. Don’t get too entrenched in your ways. Adapt. I think that, right now, is the most important thing an editor has to do, because the changes are so constant and profound. That said, at the same time, know who you are and know what your magazine or brand, if you will, is, and make sure that as things change, you’re true to the essence of what you’re making.

On what he would have tattooed upon his brain that would be there forever and no one could ever forget about him: He tried. (Laughs)

On what someone would find him doing if they showed up unexpectedly one evening at his home: Lately, I’ve gotten into drawing. (Laughs) So, I’m drawing madly when I go home. I watch TV and eat. I hang out with my friends and I also do work.

On what keeps him up at night: Everything, I can’t sleep.

|

And now the lightly edited transcript of the Mr. Magazine™ interview with Adam Moss, editor in chief, New York Magazine.

Since 1988 when you launched 7 Days Magazine, I have followed your career, and 7 Days was a great magazine while it lasted, but you have continued the greatness. I was Googling your name, as I do with everyone I interview, and I was stunned that under your name on Google the only title you have is American editor. You are one of the most celebrated editors out there; were, in fact, named Editor of the Year, yet you aren’t a celebrity editor. Why is that?

Why am I not a celebrity editor? (Laughs)

Yes, you are a “celebrated” editor, but you’re not a “celebrity” editor.

Yes, I think the reason I’m not a celebrity editor is that a ‘celebrity” editor is a somewhat different thing than an editor. And I’ve just never been comfortable doing celebrity-like things. I do my job and I hope I do it well. The more performance aspects of being an editor were never something that I was especially well-suited for.

You mentioned in your 50th anniversary issue of New York Magazine that you fell in love with the magazine’s cover, where the picture and the headline were in unison, and you never looked back. You knew you were going to be the editor of the magazine you fell in love with. Can you tell me a little bit about your concept of editing and creating a magazine?

Well, of course, it’s changed over the years. Early in my career, I was very lucky to have worked at Esquire when Phillip Moffitt was the editor. He was fairly new to editing, certainly brand new to editing when it came to a magazine the scale of Esquire. So, to help him he brought in all of these legendary magazine editors from the ‘60s and ‘70s. And I was a junior editor at the time, and as he was being taught by this group of veterans, so was I.

So, my original concept of being a magazine editor was being an editor of the type that proliferated, and what I still think of as the Golden Age of Magazines. That was a terrific learning experience. I have tried to bring those old values of magazines as a kind of theatre, really, to the work I’ve done in other later eras.

Now, being a magazine editor is something else entirely, because you’re not only dealing with the printed page, you’re dealing with material that gets read, consumed, viewed in all sorts of other ways. It’s a much more expansive role. And I’ve learned as I’ve gone along, as I think all editors have. I’ve learned how to adapt the original values of storytelling, and of interesting and sometimes exciting an audience into the modern era with material consumed in video and digitally, interactive digital and all of the other tools that are available right now.

Needless to say, you ended up being an excellent student of all of these changes.

(Laughs) Well, thank you.

New York Magazine won the overall Magazine of the Year when ASME gave the Ellie Awards, in terms of both the digital and print. Your print magazine is now biweekly and yet, you create covers that people talk about. You give the feeling that you’re Print Proud Digital Smart. How do you balance that?

Adam Moss: By hiring good people who know things that you don’t know. And then you learn from them and try to help them think about things in a certain way, but essentially you let them do their jobs. As everything gets more complicated, the role of an editor is to hire specialists and let them do their thing.

Do you feel that you’re now more of a manager, rather than an editor?

I certainly enjoy editing much more than I enjoy managing. (Laughs) But yes, inevitably, as the organisations that we run, in order to put out magazines and other content, get bigger, you have more and more the job of management, which is a necessary evil.

Yet, you as an editor, believe that great magazines are steeped in point of view, voice, and tone.

Yes, and that’s your main job. Your main job is to understand what the point of view ought to be and to constantly evangelise it within your own organisation, and try to coerce the organisation to adapt and speak in that point of view. That’s an essential job.

However, you’re no longer just ink on paper, you’re all over the platforms. How do you decide what content goes where? This is a great story for print and that is a great story for the web? Do you struggle with those types of decisions when you read a story? Or do you never ask yourself those kinds of questions?

Well, you ask yourself where the audience is for an individual story. And the answer is usually obvious. But often, very often, you publish it in more than one place. Certainly, anything that is in the print magazine is then published on “Vulture” on “The Cut” or “Daily Intelligencer.” And often, something published on Daily Intelligencer also runs on The Cut because it’s of interest to The Cut reader; it’s of interest to the more politically-obsessed Daily Intelligencer reader. You just have this huge canvas now. And you use it in the most creative way that you can think of to reach the maximum audience that story might get.

One of the great things about magazines these days and their distribution digitally and the way that the magazine business has changed is that with any individual story or piece of content, you are reaching so many more people than you could ever have reached when magazines were just print.

One of the more famous, or maybe infamous would be a better description, writers of our time by the name of Michael Wolff, wrote a profile about you in 1999. He wrote that when you started at The New York Times Magazine you were an anti-Times sort of figure in the middle of the Times, because you were more into storytelling. As we look at long-form journalism today, do you have any fears that between digital, social media, and a President who believes media is the enemy; are we reaching a danger spot, in terms of long-form journalism and storytelling in journalism?

I think there are lots of threats to what we do, but I don’t believe long-form itself is in danger. In fact, because you can reach so many people through digital distribution, you can find readers for almost anything. And there’s a big, big audience out there for our longer stuff. Our longer stuff tends to do way better than the shorter stuff. It’s a good business to be in to make longer-form journalism. People really like stories and they like storytelling.

And so, we publish a lot of long-form and we publish way more long-form than we did when I first got here 14 years ago. We also publish a lot of shorter stuff definitely, but we publish a lot more material period. We’re publishing about 140 things per day, so that’s a big difference from when I first got here when we were publishing maybe 30 articles per week.

|

So, while the printed platform is biweekly, the brand itself is now by the hour, by the minute, by the second…

By the minute, exactly. (Laughs) When we went biweekly, the point that we were trying to make was that we were trying to adjust to the way in which people now read. They want an instant response to what is happening in the world and we provide that. And then they also want a deeper, more meditative content, not necessarily on a weekly schedule, which made us comfortable with having our stuff read on a biweekly basis.

During these 14 years that you’ve been at New York Magazine, you have laid the groundwork for so many imitators. Your cover designs, what you’ve done to the covers of New York have been imitated worldwide. Wherever I travel overseas, people are always referring to the covers of New York Magazine.

Adam Moss; That’s good to hear.

Do you still feel that the cover of a printed magazine today makes an impact? Is there somehow a halo around a printed magazine cover that does not exist in digital?

Probably. The cover is no longer really to sell magazines on newsstand. As newsstands have become so much less important to all of us, the cover has a different function. It is basically the brand statement of what we make. It declares what we think is important or interesting; it declares our voice. Also, it’s an amazing document for the purposes of social media. Social media takes your cover and distributes it all over the place and it becomes an advertisement for the magazine that’s actually more important than it was originally meant to be when it was to stimulate newsstand sales.

And do you think that is a good thing or a bad thing?

I try not to think in those terms, because everything is both. Things change; there’s no fighting the things that change. And you just have to adjust to them and think of them as opportunities and not as problems. And I think basically most of the changes have been, not all, but most, have been for the better.

I heard your CEO last week in New York when she was talking about the revenue from digital; you’re one of the few magazines that is making more money from digital than print.

Yes, we’ve been at it for a very long time. We’ve been at it way longer than most, if not all, magazines. The story of New York and its digital incarnations have preceded me being here. It was kind of coincidence that the previous owners of this magazine went into a joint partnership with Cablevision in order to do their website. There was a website called New York Metro, and New York Metro had the magazine on it and it also had listings and that sort of thing. It was ahead of its time in that way, but it had one other thing that was crucially important, which is the reason that Cablevision wanted the partnership because they wanted to promote a fashion show that they had called “Full Frontal Fashion,” I believe. And what that meant was the promotional device was to run the runway pictures on the website. This was before any fashion designer had his/her own website. So, we were the only place you could get runway pictures, which meant that we got a lot of traffic from the very beginning.

Before anyone was in this business at all, The New York Metro website was attracting a lot of people and it was attracting the sort of people who, if you were also an advertiser for a high-end luxury product, that was the only way you could reach them. So, from the very beginning, New York Magazine’s website was profitable, which was really unheard of.

And what that meant was when the Wasserstein’s bought the magazine, and when I got here, the web wasn’t looked at as dangerous. The web wasn’t looked at as something that was going to steal business, the web was looked at as actually a way to build business. So, the logic of investing into the web, making our site a news site, was kind of obvious. And so, we did that very early. It was successful and the way we were doing it was successful and was a sort of model, which we did it first with food and then entertainment, etc. That model was easy to just keep replicating. And we’ve built the modern digital New York Magazine from a position of strength.

And now, you’ve been imitated on both sides. Sports Illustrated just moved to a biweekly schedule in their print edition. Wired is starting a paywall for their digital content; why do you think the majority of some of the “smartest people on the face of the Earth,” magazine editors and publishers, created this welfare information society and gave away the only thing that they actually create?

It was similar to what almost all content fields did. The music business was famously very confused by the beginning of the digital age. People needed and wanted to get information for free and from the music side, it was easy to steal music. Everybody has been confused about how to make money off of digital habits. And I think the magazine business has been confused too. And it’s only now beginning to reckon with that in a serious way. That’s why you’re seeing paywalls and ecommerce, which we do here, actually very successfully. But also, our experience was that you could actually make advertising money off of the digital content. And so, we did that too.

It’s very confusing. I mean, the smartest people on earth, as you put it, (Laughs) have a lot of reason to be confused. And have had a lot of reason to be confused, because it’s confusing.

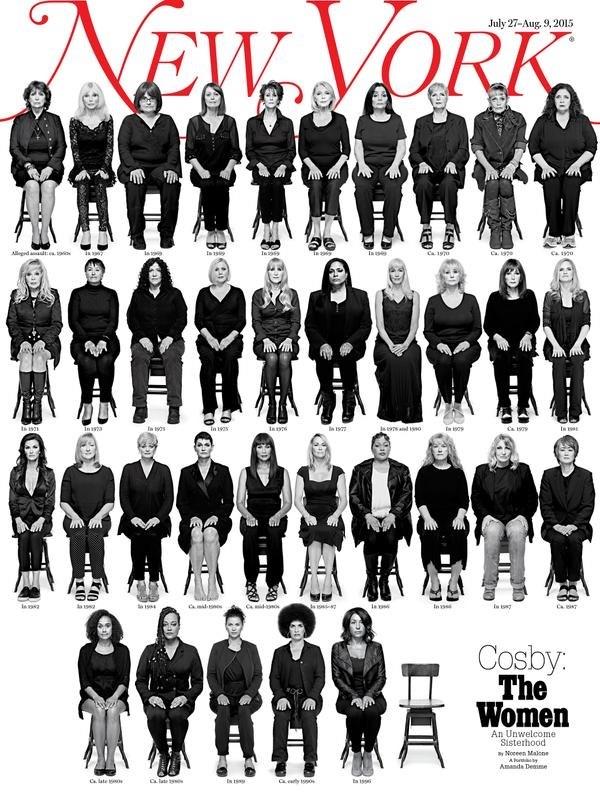

Everyone I’ve talked to, once they found out I was interviewing you, had nothing but compliments to say about you, such as the most humble editor, a hardworking editor. And these words were from people who don’t pay compliments easily. So, you have this halo around you, yet as I stated in the beginning of this conversation, you’re not a “celebrity” editor. Do you thrive on letting your work become the celebrity, such as the cover of New York Magazine with the Bill Cosby accusers on it? Do you feel the brand is a projection of Adam Moss?

It’s a projection of a group think, and it’s the editor’s job to get the right group together to have that group think. So, it’s not because of me exactly, but it is a projection of a worldview that I’ve helped shape here. And it’s the product of a lot of people thinking. I can’t say that I’ve done anything particularly on purpose. The reason that I’m not out there giving parties and that sort of thing is because I can’t. (Laughs) Not because I willfully decided that was a bad tactic. I actually think it’s a good tactic. I think it’s often very helpful for places to have magazine editors with a higher profile. But for me, that’s just not the way that I work. For me, what it’s about is the work, and that’s what interests me.

|

And correct me if I’m mistaken, but aren’t you the longest-serving editor of New York magazine so far?

Yes, that is now true. It happened about two years ago that I passed Ed Kosner, who previously held that honor. I’ve been here almost twice as long as Clay Felker himself was here. I’ve been here forever.

What can we expect in the next seven years, since we’re going in multiples of seven, you’ve been there 14 years now?

I can’t even tell you what to expect tomorrow. (Laughs) This business changes so fast. And it’s a race to catch up to the changes in the business and also, of course, the changes in the world and what we cover.

What piece of advice would you give upcoming magazine editors, future industry leaders? From somebody who has been there and done that, adapted to all of the changes; what piece of advice would you give them?

Listen and watch. Don’t get too entrenched in your ways. Adapt. I think that, right now, is the most important thing an editor has to do, because the changes are so constant and profound. That said, at the same time, know who you are and know what your magazine or brand, if you will, is, and make sure that as things change, you’re true to the essence of what you’re making.

If you could have one thing tattooed upon your brain that no one would ever forget about you, what would it be?

Adam Moss: He tried. (Laughs)

If I showed up unexpectedly at your home one evening after work, what would I find you doing? Having a glass of wine; reading a magazine; cooking; watching TV; or something else?

Lately, I’ve gotten into drawing. (Laughs) So, I’m drawing madly when I go home. I watch TV and eat. I hang out with my friends and I also do work.

My typical last question; what keeps you up at night?

Everything, I can’t sleep.

Thank you.

More like this

The Mr. Magazine™ Interview: Print is never going to go away, says Hearst’s Joanna Coles